Opinion

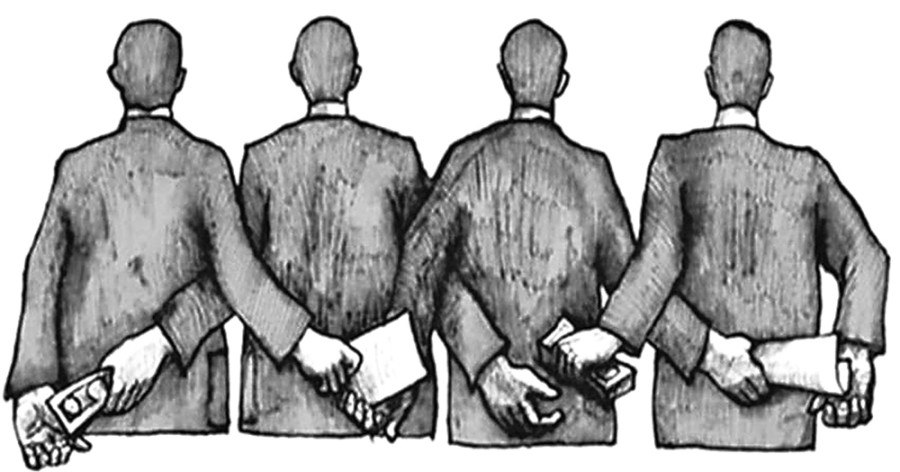

Abusing authorities

Instead of bringing down corruption in the country, the CIAA chief’s impeachment will further aggravate it

The legislature and the executive have been in disagreement with the constitutional anti-graft agency, the Commission for the Investigation of Abuse of Authority (CIAA), about clipping the agency’s wings to investigate improper conduct by public officials in the new constitution. Unlike earlier, Article 239 of the new constitution empowers the CIAA to investigate only corruption cases, not improper conducts.

Since its inception in 1992, investigations into the abuse of authority by public officials have been categorised into two groups, namely corruption and improper conduct. The agency was empowered to investigate and prosecute both crimes. This power was also retained in the Interim Constitution 2007.

Upon sensing the move to curtail the power of the agency during the drafting of the Constitution, the CIAA had expressed its displeasure citing the country’s commitment to the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). The UNCAC has envisioned a broader role of anti-graft agencies.

Defining corruption

Since all forms of corruption are an act of improper conduct or anuchit karya in Nepali, there might be difficulties differentiating between the two. Explanations on what constitutes an act of corruption and improper conduct are given in the Corruption Prevention Act 2002 and the CIAA Act 1992. Though there is no sharp demarcation between the two, we can assume that acts of corruption are adjudicated by the court of law. If found convicted, public officials have to serve a mandatory prison sentence besides fines, property confiscation and disqualification from joining public service.

On the other hand, improper conduct entails departmental actions where the maximum penalty is job termination. To constitute an act of corruption, it requires an exact assessment of the financial losses that have to be recovered from the convict. Compared to corruption, improper conduct can be regarded as a smaller evil. However, in practice, the line between the two can be wafer-thin. Some countries divide corruption into (a) abuse of authority—also called ombudsmen function and (b) improper conduct. We required a nuanced definition of corruption but the global move to define corruption is towards a broader definition. This is the single reason why the global anti-corruption instrument, UNCAC, does not explicitly define corruption.

It is clear why the drafters of the constitution have decided to curtail the power of the CIAA. Their earlier stance was that ‘the power to investigate improper conduct’ should not be in the realm of the CIAA, pointing towards a more executive function. However, the impeachers of Lokman Singh Karki have blamed him, among others, for running ‘a parallel government’. The move here is to stop him from issuing suggestions, directives and interfering into executive functions under the garb of investigating the acts of improper conduct. Earlier in the month, in a writ petition filed by seven doctors, the Supreme Court issued an interim order against the CIAA, as its action goes beyond its constitutional jurisdiction.

Power tussle

It is also worthwhile to ponder over the possible implications of curtailing the CIAA’s power. We should not forget that this has come at a time when the agency is seeking to broaden its scope of jurisdiction. For example, it seeks to investigate corruption cases committed by the private sector and NGOs, as implied by Nepal’s ratification of UNCAC. The CIAA has been complaining over its limited investigative powers for a long time.

Concerning investigation and prosecution of corruption cases, the final adjudicative power rests with the court. There exists a subtle rivalry between the CIAA and the court. For poor conviction rates, particularly of high profile cases, the CIAA is blaming the court for its relaxed attitude towards corruption cases while the court accuses the agency of poor investigative skills. The recent decision by the Supreme Court quashing the order of the Land Reform Office, Lalitpur has pushed the CIAA into a legal quagmire. If I understand the verdict clearly, it calls for the CIAA “to find” or prove the charges before issuing a directive to the concerned agency for further investigation.Why would the CIAA issue directives for further investigation if it already finds the accused to be guilty?

Similarly, concerning investigations into improper conduct, there exists a tension between the CIAA and another constitutional agency, the Public Service Commission. The CIAA cannot fire public officials under the charges of improper conduct for it can only issue directives. The one who hired the concerned party retains the ‘right to fire’. A majority of the directives issued by the CIAA remains unheeded.

Without completely rationalising our legal and institutional arrangement to fight corruption, merely clipping power here and there will not help mitigate the scourge. This is the single reason why Karki’s impeachment will not lower but further aggravate corruption in the country. The impeachers of Karki are advised not to wash dirty linen in public for they have already shamed the country by blaming Karki for the country’s poor standing in the global Corruption Perception Index (CPI) ranking. Karki is not a saint. As the Nepali saying goes, we do not have people washed in milk, that is, without sins. However, by correlating the CPI ranking with the performance of the CIAA chief, the impeachers are indirectly personifying his image.

Manandhar is a freelance consultant

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu