Opinion

Not so new

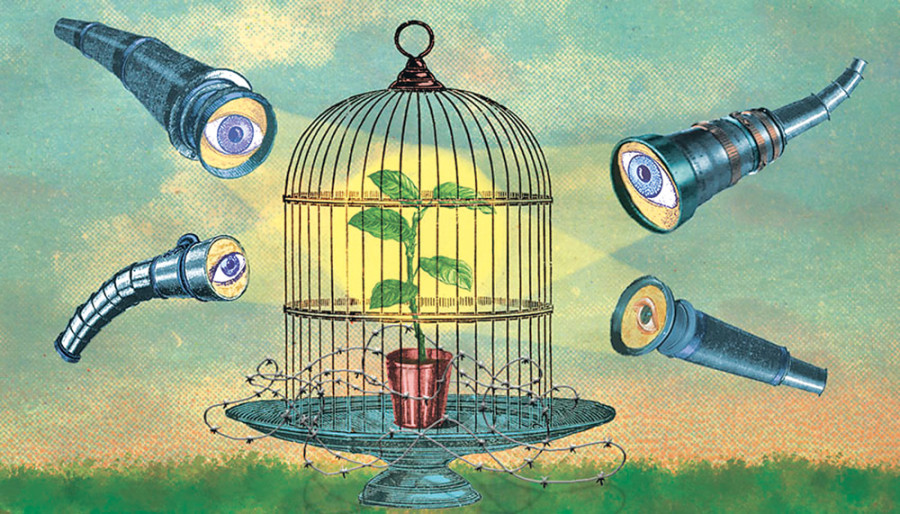

Bhattarai’s initiative has shown some promising signs, but it is beset by significant challenges

Jainendra Jeevan

Finally, the Naya Shakti Nepal (NSN) party came into being on June 12. Sixteen months back when he was still the number two leader in the then Unified Maoist party, NSN’s founder and former Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai had publicly advocated the necessity of his ‘new force’. He and his associates quit the Maoist party some nine months back. They maintain that their party is really ‘new’, and thus qualitatively different from other parties. They are aware that Nepali people are disappointed with almost all the major political parties as they are corrupt and inept, and that most of the fringe parties are just good for nothing, besides being equally corrupt. They have also rightly assessed that fed up with the plethora of parties, their fights and subsequent splits, people would welcome a fresh party provided it is big enough, capable and ethical. Now the million dollar question is: Will the NSN withstand these tests? Yes, Bhattarai seems to have a desire to do something for the country; but the problem is that he is a ‘thought leader’, not an ‘organisational leader’. How will a leader with poor organisational skills ensure electoral success for his party? And how will the party fulfil his ‘dreams’ without being voted to power?

Development-focused party

A sizable faction of ex-rebels has successfully metamorphosed into a non-Marxist, non-communist ‘Left-Democratic’ party. While one faction of the erstwhile rebels—its mainstream, the Maoist Centre—is ideologically confused, the Mohan Baidya-led faction remains as dogmatic as before and the Netra Bikram Chand-led faction intends to go back to violent insurgency, Bhattarai has transformed his faction into a development-focused party. This I think is the NSN’s greatest service to the nation. As economic development is the most coveted yearning of Nepali people who are sick and tired of the politics of various ‘isms’ and agitations, intellectuals should have appreciated this instead of criticising and mocking Bhattarai’s initiative. Yes, on his part, Bhattarai too should ponder why he is not popular, especially among intellectuals, and correct himself.

In terms of ideological transformation, the NSN has leaped past even the CPN-UML, the ‘left-to-the-centre’ party that believes in and practices bourgeois realpolitik rather than communist ideology and that has so far not changed its communist nomenclature. Once a year, on the death anniversary of its charismatic leader Madan Bhandari, the party remembers ‘People’s Multiparty Democracy’, a concept introduced by him to gradually divorce the party from its communist past. The poorly explained half-measure—adopted by the 5th General Convention of the UML a quarter of a century ago, and never updated since—has become time-worn. Unlike the UML, Bhattarai and his associates have been bold enough to abandon outdated brands and principles that they know they cannot or will not use.

Whether or not they are the proverbial morning of a bright day, the NSN’s party workers and volunteers meticulously avoided the occurrence of traffic jam that their party’s inaugural rally could have caused. They cleaned the rally site after completing the ceremony. For publicity, they used electronic media and discarded the practice of wall paintings. They did not resort to forced donations. The whole ceremony was conducted without the usual ‘chief guest’ and all similar nonsense and protocols. Bhattarai invited the leaders of all political parties on the occasion; during his hour-long speech he did not criticise others the way he did before. He also paid tributes to Prithvi Narayan Shah and BP Koirala, among others. Though not as big as publicised, the crowd was impressive as well as disciplined; so was the management.

No teamwork

This does not mean there is no other side to the NSN. The NSN was conceived by the synthesis of two factors—Bhattarai’s frustration with Prachanda and the mercurial rise of the Aam Aadmy Party (AAP) in Delhi. Prachanda never wanted to see Bhattarai as the top leader of the Unified Maoist Party. Weak in organisational management and practicalities, Bhattarai had far fewer followers than did Prachanda. Thus, Bhattarai lacked the strength and skills to challenge Prachanda, let alone defeat him within the party. To fulfil his ambition of becoming the top leader, Bhattarai had no choice but to form a new party. He was also encouraged and inspired by the AAP and its agenda of clean government, effective delivery and austerity and simplicity in public life, which he wanted to replicate here. But the situation in Delhi is different from that in Nepal and so are the AAP’s dynamics from the NSN’s—a point Bhattarai seems to have missed.

A serious drawback of Bhattarai’s politics is his demonstration of love for divisive identity politics, probably with an eye on ethno-regional vote-bank—a peril that has been polarising communities and weakening the state for quite a while now. The Nepali people have also been asking Bhattarai and his comrades to publicly apologise for the violence, killings, destructions, terror and pain their decade-long bloody insurgency inflicted. But instead of obliging humbly, they are still defending and sometimes even glorifying their actions. How and why millions of people who suffered directly or indirectly at the hands of the Maoists will trust, support and vote for the NSP—Bhattarai does not seem to have mused either.

Ex-Maoists comprise a majority of the NSN rank and file, although to make it more colourful, Bhattarai has invited some professionals, celebrities and intellectuals to the party. Although few in numbers, staunch supporters of a free market economy have also been welcomed. Amidst their inherent ideological tussles, it will be an enormously challenging task to make the party a cohesive and functioning body. It could even be a non-starter, some signs of which have already been detected. During their ‘discussion session’ (other parties call it a ‘closed session’), participants were sharply divided on the

question of whether to pursue a ‘Left-Democratic line’ or a ‘Democratic line’.

Even trickier will be to define and implement a workable blueprint of ‘socialism’ as stated in the party’s political report. The NSN’s dream of socialism might collapse under the massive weight of its own burden that consists of everything from prosperity to development to social justice.

The party could not nominate office-bearers and central committee members as there were too many aspirants for the positions. This depicts the (same old) mindset of the (same old) ‘new’ people. Last but not least, the NSP has so far become a one-man show. From an all powerful leader to the face and voice appearing in the party’s publicity materials, it is only Bhattarai; no teamwork is in sight. How a single leader will effectively and in a ‘new’ way run this economically poor, socially complex, politically problematic and really pluralistic country in the most difficult time of its history—Bhattarai does not seem to have contemplated at all.

The author can be contacted at [email protected]

9.6°C Kathmandu

9.6°C Kathmandu