Opinion

Neighbouring with the north

When all the countries in the world started to link with China, Nepal quietly delinked

Ram C Acharya

A few months ago during the fuel crisis, a team of Members of Parliament (MPs) had visited Nepal’s northern districts bordering China to learn about the mountain passes that were used for trade between the two countries in the 19th century and see if they could be used to import oil. With no options left, the lawmakers went to look for these routes as if they were searching for someone who had recently been lost in the forest. This episode raised many questions. Where was the country’s plan in the past? Why did the country never bother to think of these roads? Why was it so clueless about such vital issues? The fact that things have descended to this level is deeply disturbing.

Compounding the absurdity, the country located in Nepal’s blind spot happens to be the world’s largest manufacturer, the world’s most populous country, the world’s largest exporter and second largest importer of goods and services, the most favoured destination for foreign investors and the world’s top tourism spender. Above all, it is one of the only two neighbours Nepal has.

Bringing China on board

What went wrong? As China’s growth astonishingly went into high gear in the last three decades, the world made great efforts to integrate with it economically. Nepal took the opposite stand. The old infrastructure crumbled, and a new one never took hold. It was convenient that the only thing that interested Nepal, Chinese aid, did not require any roads. Trade between the two countries, that was so vibrant centuries ago, has evaporated. Nepal is less integrated with China in terms of trade to GDP ratio today than it was in the 19th century. The low level of trade with China has held up the economic development of Nepal’s northern regions. China, which consumes 10 percent of global exports, buys less than three percent of Nepal’s exports. Yet, Nepal and China are countries that share borders. For a landlocked country that is bordered by only two countries, having connections with multiple decent roads with both the neighbours should have been the first priority. Not so in Nepal.

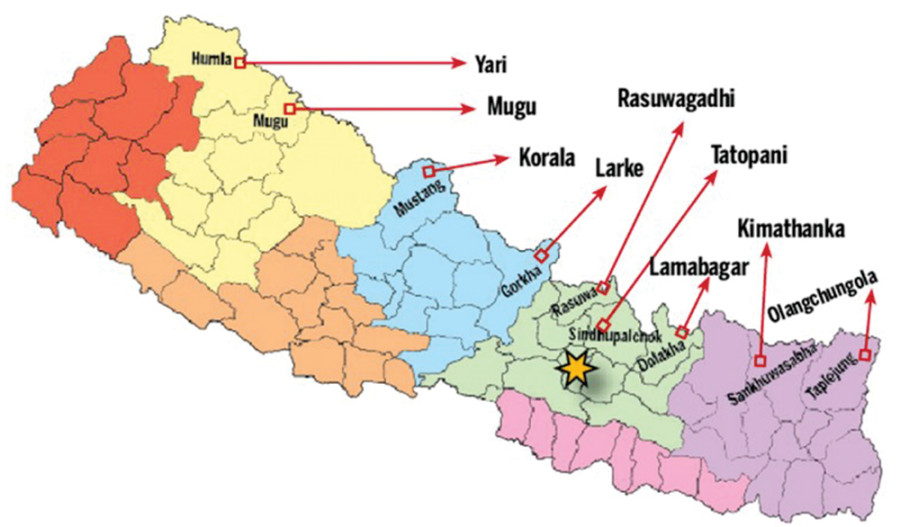

The difficult terrain in the north makes road building more expensive, but that does not justify neglect. It demands a more sustained and well thought-out plan. The inter-generational benefits of such infrastructure in the north far outweigh the one-time costs of building it. In fact, if Nepal connects with China by road networks, the mountains, which look like insurmountable barriers, would turn into assets. We do not know what the MPs decided at the end of their exploration, but the message is clear: Action is urgent. Nepal must, as a top priority, start upgrading these routes into decent all-seasons roads extending from the far west to the far east. Nepal should have signed a transit treaty with China a few decades ago. Besides expanding Nepal’s options, having transit treaties with both the neighbours will encourage them to respect the spirit of the pacts.

Engagement, not handouts

Nepal should stop thinking about what China can give in aid and think about how to engage it in economic integration. Nepal should graduate from thinking of China and India as donors providing short-term handouts to seeing them as long-term economic partners and competitors. It is a tough call, but this is the only way to make Nepal a prosperous nation and a respectable neighbour in the middle of two giants. China would be interested in having stronger economic integration with Nepal, but as it is a small country (in terms of production, China equals 524 Nepals), it is in greater need of integration. And in order to integrate and take advantage of the Chinese market, Nepal needs to make several policy changes.

The most important one is creating a symmetric market framework—infrastructure, rules and policies—for both the countries. Nepal should sign a free trade agreement with China like it has been moving towards a free trade deal with India and the other South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (Saarc) countries. And with regard to foreign direct investment, Nepal needs to have global symmetry: Welcome investment from all the countries in the world and treat all the investors equally. Once the state has undertaken such a balancing act, it will be immaterial with which country Nepal’s economic integration deepens more. This will be decided by the private sector based on market signals leading to natural economic integration—exporting to countries where prices are higher and importing from countries where prices are lower. And it will be the most efficient way of integrating. However, due to the present asymmetrical framework, Nepal’s trade with China amounts to very little while India accounts for two-thirds of its trade.

This brings us to the fuel market in Nepal. Other countries make serious efforts to dismantle or regulate monopolists because they charge higher prices and collect rents at the expense of the public. In contrast, Nepal has created monopolies in two stages: Nepal Oil Corporation (NOC) at home and Indian Oil Corporation (IOC) abroad. Nepal has thus cornered itself as IOC’s captive fuel market. What it should do is throw out both the monopolists. At home, the private sector should be allowed to import and compete with NOC; and abroad, infrastructure should be developed so that fuel imports through or from China become equally feasible.

Bottom line

Nepal should do the right thing: Aim to graduate to a competitor in the economic sphere with its neighbours. It should complete market framework policies to ease economic integration with China. Whether building infrastructure, dealing with trade, foreign direct investment and transit treaties, providing monopoly rights or awarding contracts, it is prudent to follow symmetric policies with both the neighbours. Such a balancing act will enable Nepal to pursue independent economic and social policies at home besides making them more effective. The explorer MPs may have been disappointed at finding that the old trade routes across the Himalaya are no more functional. It needs to be said that it was nobody else

but the Nepali politicians who brought Nepal to this sorry state. Will they act differently this time?

Acharya is an economist

17.9°C Kathmandu

17.9°C Kathmandu