Opinion

Show some empathy

It’s wrong to mock marginalised groups engaged in social justice movements

Tirtha Raj Bhatta

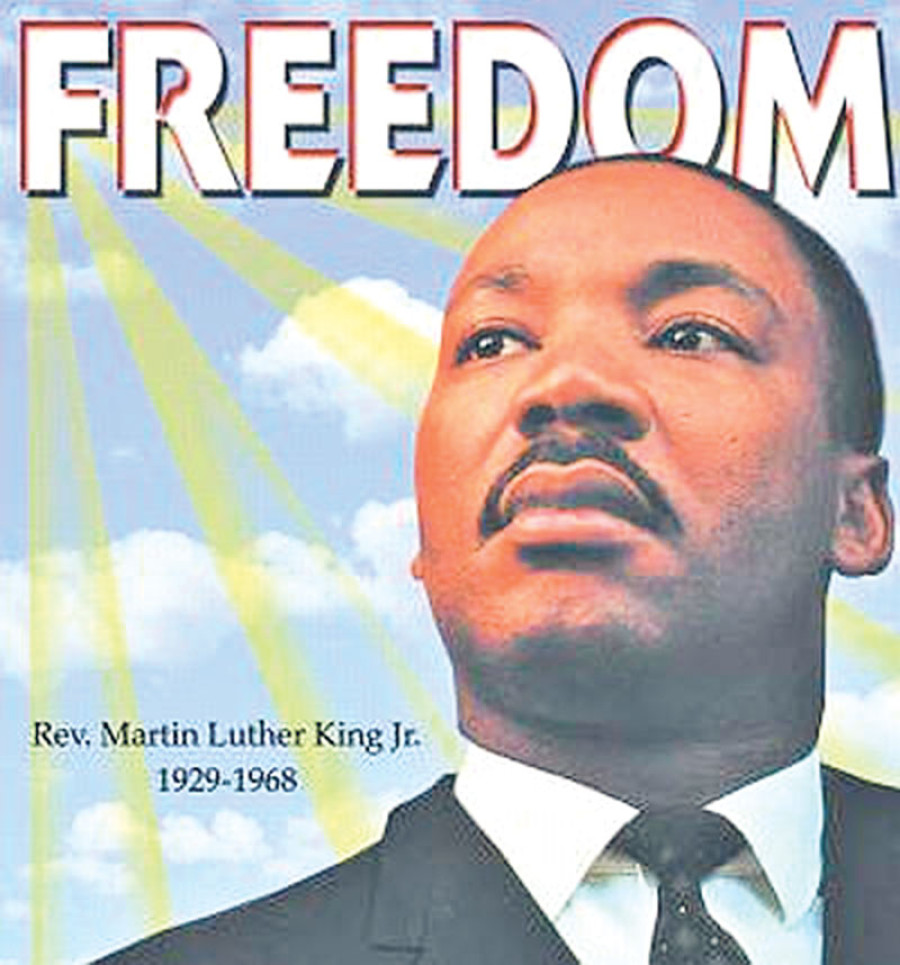

The leader of the US Civil Rights Movement, the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., constantly challenged us to identify structural or institutional causes of social inequalities. Through the Civil Rights Movement, he was able to expose institutional mechanisms like access to health care, segregation and wage discrimination as being responsible for producing racial inequalities in a range of outcomes like health and education. A lifelong champion of social justice, he organised successful social movements that ended legalised racism and reinstated voting rights for African-Americans in the US. It is important to revisit Dr King’s legacy to understand how far out of sync we are from his ideals when we deride Nepali marginalised groups engaged in social justice movements.

Struggles for social justice challenge the existing power dynamics, hence they are likely to invite vigorous opposition from groups that have been enjoying privileges. Likewise, recent mass movements by the Madhesis, Tharus and Janajatis have had to face ridicule and deep suspicion from the so-called higher caste groups. It is sad to see negative responses, particularly at a time when their solidarity with these movements could have heralded the beginning of a progressive era in Nepal. Our unwillingness to embrace struggles for social justice by our fellow Nepalis suggests a lack of understanding of the structural roots of centuries of injustice like state-sanctioned linguistic, cultural and economic marginalisation. It also indicates a lack of empathy for the plight of fellow Nepalis. Both of these were essential components of Dr King’s lifelong social activism for a more just and compassionate society.

Blame the victim

Growing up in a centralised and deeply unequal system in Nepal, we have come to accept social inequalities as something inherent or intractable. We are educated to ignore the role of social, economic and political systems in shaping people’s lives. Our education system, structured to produce obedient citizens, has reinforced such a depoliticised and decontextualised understanding of social inequalities. We are encouraged to find fault in the characteristics of individuals, not in the larger social, economic and political systems that place them at a disadvantage. Consequently, we turn our backs on our fellow human beings with a “it is not my problem” mentality.

This type of victim-blaming mentality was on full display when individuals representing the so-called higher caste groups mocked and ridiculed the Madhesi, Tharu, and Janajati struggles for a more just political system. The intent of their ridicule was to mask the hegemony of their caste groups by pointing out individual successes or failures of people from the marginalised ethnic groups. For instance, they tend to juxtapose poor Brahmins/Chhetris with rich Madhesis in their attempt to trivialise systematic inequalities by equating it with differences at the individual level. They fail to realise that a few privileged Madhesis, Tharus and Janajatis do not, in any way, alter their hegemony or power dynamics that has existed for centuries. Such a failure on the part of the higher caste individuals has impeded the progressive change sought by Nepali marginalised groups. Attributing social inequalities to individual failures creates a narrative that supports the status quo, and hence, does not provide incentive to those in power to effect change.

Chasing the dream

In the long run, the social inequalities that are deeply entrenched in a social system tend to be taken for granted or become naturalised. Dr King vigorously challenged the naturalisation of racial segregation that was so pervasive and deeply entrenched in South Africa and the US. The naturalisation of social inequality between whites and blacks was a manifestation of the deeply unjust system that persisted even after the abolishment of slavery in the US. Dr King argued that the manifestation of social inequalities cannot be attributed to the differences in individual characteristics. For instance, racial differences in the IQ level cannot be understood by examining individual differences between blacks and whites. It can only be understood in the context of slavery and the continuation of social and economic marginalisation.

A naturalised understanding of the social system makes us believe the myth that social inequality is inevitable. Dr King’s vision challenges us to rise above our material comfort to confront the myth that has been created to perpetuate the existing inequalities. He also encourages us to embrace a humanistic orientation to address social inequalities. Such an orientation requires us to transcend geographical boundaries because each one of us is part of what Dr King called a “global village”. For instance, higher caste individuals living in Kathmandu or other regions should be willing to express solidarity with social justice movements like that of Madhesis, Tharus and Janajatis even when it does not affect their own livelihood.

Dr King’s humanistic concern about the plight of the poor was not a criticism of rich individuals. He also provided strong support to those fighting apartheid in South Africa. Similarly, he expressed outrage at war atrocities committed in Vietnam. Inspired by Dr King’s ideals, we should be able to rise above our material comforts to express solidarity with the social justice movements happening in Nepal. Regardless of our geographical location and our caste or ethnicity, we are connected with fellow human beings at a spiritual level. Hence, our spiritual connectedness should make us empathetic to their struggle for social justice. Dr King also felt such spiritual connectedness. He was driven

by an understanding that “injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere”.

Bhatta is a PhD candidate in the department of Sociology at Case Western Reserve University

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu