Opinion

Treasures in ruins

The destroyed cultural heritages of the Kathmandu Valley were the heart and soul of the country’s identity

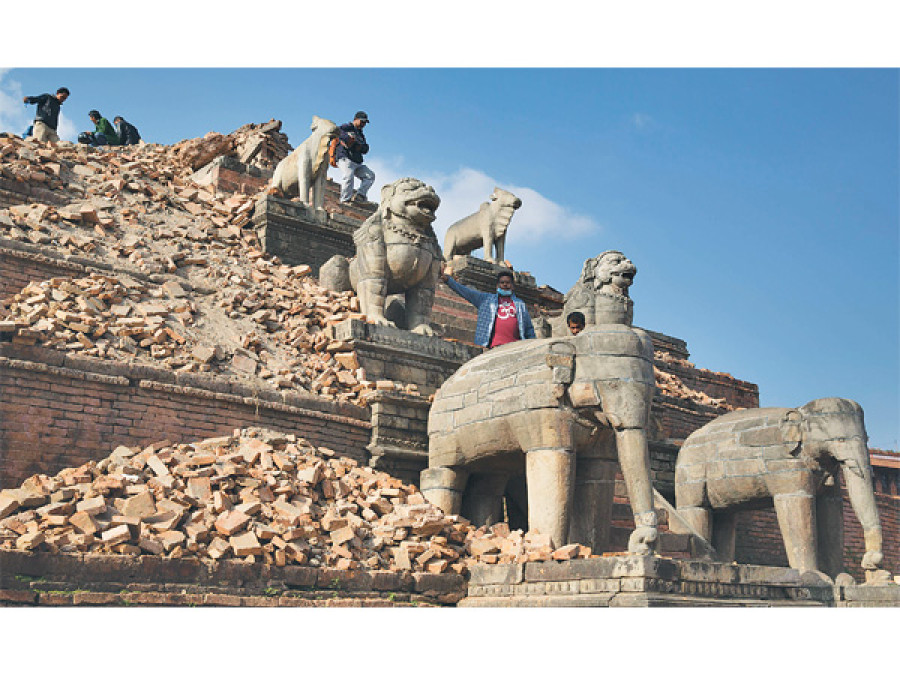

The deadly 7.9 magnitude earthquake on April 25, together with its numerous aftershocks, has devastated the Kathmandu Valley’s cultural heritage. Beyond the loss of human lives and the priority given to looking for and rescuing survivors, it is a terrible tragedy for the whole of Nepal. The damaged buildings were the heart and soul of the country’s identity. They sustained a sense of pride among all Nepalis. This destruction has been a particular blow to the Newars, whose architectural achievements and historic monuments have greatly suffered. In addition, these monuments were a major tourist attraction for international travellers and largely contributed to the country’s overall economy. Their loss will trigger considerable financial, political, and cultural consequences.

What’s been lost

Among the seven groups of monuments and buildings in the region that are on the list of the Unesco World Heritage Sites, three (the royal palace squares in the three ancient Malla capitals), including the nine-storey Basantapur tower in Kathmandu, have been almost totally destroyed and two others (Swayambhunath and the double-roofed temple at Changu Narayan, dedicated to Vishnu), have been partly damaged. In fact, Changu Narayan needs to be reconstructed. In Patan Durbar Square, the temples of Shanker Narayan, Char Narayan (also called Jagannarayan), and Uma Maheswar (made of stone) have totally collapsed.

Yet many other temples, former monasteries, and various key buildings have been hit. The iconic, 60-metre high, white Dharahara tower built in 1832, one of Kathmandu’s most visible monuments, has been razed to the ground. Kasthamandap, the temple that gave the capital city its name, and Kalomochan temple built in the Mughal style by Jung Bahadur along the Bagmati have been reduced to pieces of wood and rubble. More than 10 neighbourhood temples in Patan have been flattened. In Bungmati, the Rato Mastyendranath temple was destroyed during the festive performance dedicated to the god. The damage caused to the structure of Rana palaces still needs to be assessed but the nineteenth- and twentieth-century parts of Hanuman Dhoka and the Nepal Association of Fine Arts (Nafa) Naxal building now lie in ruins.

In fact, the Kathmandu Valley is a concentration of an exceptional number of historic monuments, both secular and religious. These buildings were erected between the 12th century and the beginning of the 20th century, if we include the exceptional Rana palace architectural heritage. Some chaityas are even older and date back as far as the fifth century AD. The maintenance is ensured by local bodies or by private individuals. Other sites come directly under the Ministry of Culture’s authority.

A living museum

These temples and monuments altogether represent a unique testimony to Nepali culture, with the major part belonging to the ancient civilisation of the Kathmandu Valley, which is one of the most vibrant in the Himalayas. Despite successive mega earthquakes over the ages (1833, 1934, for instance), and the current unrestrained wave of urbanisation, these temples and monuments have for the most part survived and are visited and used for various functions (both secular and religious). They are part of the recognised urbanscape; they are living places shared by all. When destroyed in the past, they were (save some exceptions) rebuilt over the centuries, approximately on the same model as before. The Kathmandu Valley is thereby an exceptional living museum of bygone ages, representing successive superposed historical layers.

Some temples have resisted more than others. Pashupatinath’s main temple has seemingly not been affected. The situation varies enormously from one place to another. Surprisingly, the five-tiered Nyatapol, the Dattatreya, and Bhairavanath temples in Bhaktapur have more or less resisted. Similarly, Patan’s stone Krishna Mandir has not collapsed. In the same manner as in 1934, the stone pavement, locally referred to as Bhairava, on which the city of Panauti is built, has preserved its main local historic monuments.

The vulnerability to earthquakes of each historical site varies according to its individual location, shape, and construction. Brick, for instance, is a better building material than mortar. Unfortunately, after the 1934 earthquake, temple repairs were hastily made, using cheap, flimsy materials (like mud and mortar). Walls held together by strong metal sheets, such as in temples at Pashupatinath, or those used in the renovation of Patan Durbar Square (Patan Museum), have proved to be more solid. The number of recent renovations, the underground structure, and the height of a building are also of great import in these matters. Whatever the case, most of the buildings have been greatly weakened.

Historical monuments play a crucial role in the symbolic imagination and are closely linked to the identity of the human groups. Temples and other outstanding buildings are vital historic landmarks. I vividly remember, in June 1973, the hopelessness of many Nepali residents of Kathmandu when the Singha Durbar Rana palace was in flames and fell to the ground. Such a desperate reaction reveals a deep attachment to the monuments of the past. In fact, monumental buildings memorialise the nation’s intermingled eras from the past. They are symbolically charged sites.

Building back

Unesco has announced an in-depth expertise of the damage “based thereon to advise and provide support to the Nepalese authorities and local communities on its protection and conservation”. Emphasis should be laid on the restoration techniques to be used, given that the 2015 earthquake has shown the extreme fragility of these monuments. Indeed, this structural weakness is apparent even in day-to-day life. In the 1980s, I myself saw the roofs of Vishwanath temple in Patan Durbar Square fall down all of a sudden during the rainy season, quite independent of any earthquake.

Past experiences attest to the fact that the UN’s cultural organisation will hardly be able to undertake the preliminary archiving work and the subsequent rebuilding task on its own. Other forms of cooperation with individual countries will be required. At any rate, the reconstruction will take many years, perhaps even decades.

Toffin is Research Professor at the National Centre for Scientific Research, France

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu