Opinion

The power and the glory

Should we allow ourselves to be shepherded and caned like beasts by a dictator for the sake of prosperity?

Abhinawa Devkota

Lee Kuan Yew, the now deceased founding father of the country, must have sighed with relief at the sight of this digital panopticon—a mechanism that could effectively probe into the recesses of the digital lives of the island’s residents. After all, Lee was the person who had vilified democracy all his life, not just in words but also in deed, while promoting discipline, harmony, and scrutiny. And now, there was a system, made in the land of freedom, which would make sure that his citizens walked in goose-step forever and effectively curtailed the already-throttled grunts for freedom in his country.

Poor Amos Yee, how could he have even imagined that he could escape the sight of this digital policeman straight from the future, when he posted a video criticising the venerable Minister Mentor after his death. With the arrest of this 17-year-old boy, the government of Singapore proved once again that it would eradicate any possible outbursts of democratic voices with the same effectiveness with which it had handled the Sars outbreak more than a decade ago and the malaria outbreak during its founding days. The founder might have died, but his iron grip lived on.

The way of Lee

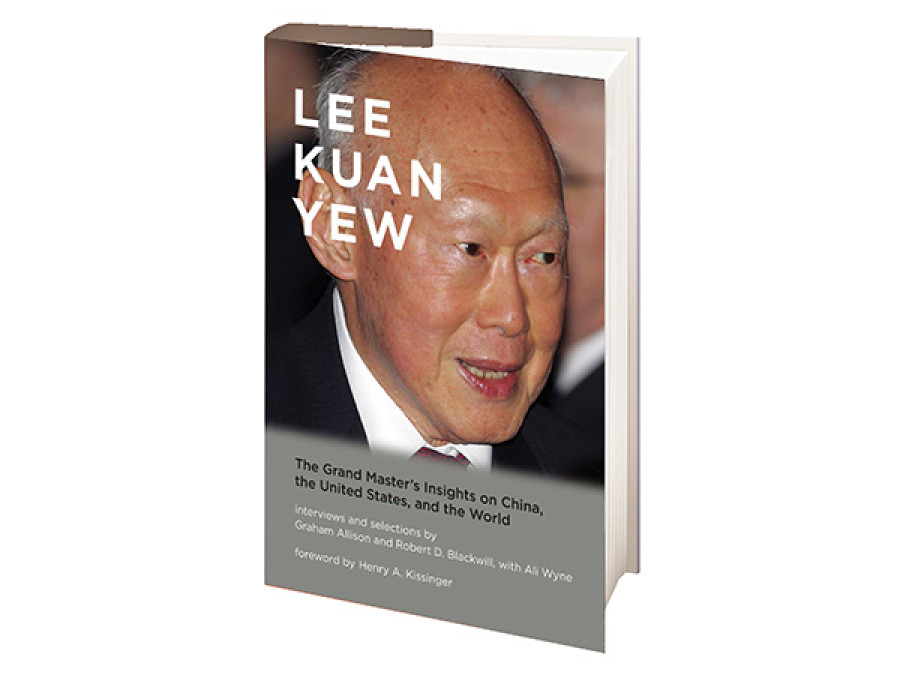

If one is to get a peek into Lee’s mind to understand his thoughts and beliefs, then there is hardly any better read than Lee Kuan Yew: The Grand Master’s Insights on China, the United States and the World, a selection of interviews coauthored by Graham Allison and Robert D Blackwill, with Ali Wyne. And, not to forget, a foreword by Henry Kissinger. Don’t get put off by its length. Though less than 200 pages, the book contains invaluable observations of the Wise Man of the East, one of Lee’s many monikers, that help us understand what went behind the making of the man who single-handedly challenged the values and systems of democracy that have become the political and philosophical hallmarks of the 20th century.

Lee’s observations of the world are mediated through the prism of realism, which would make even a realist quail. He blithely heralds the age when China rules the world, though he is of the opinion that China is still a few decades away from claiming the US’ position. He assesses every move and step of the contesting world powers with an air of superiority and confidence that even the best in this field seem to lack (given the tumultuous times we are living in) and is all praises for Friedrich Hayek’s defence of classical liberalism and Herbert Spencer’s Social Darwinism. He credits the Japanese invasion of Singapore with teaching him the meaning of power and the British overlords for edifying his young mind with the know-how of governing people and dominating them.

But the most problematic portion of the book seems to be Lee’s observation of human nature. “Human beings, regrettable though it may be, are inherently vicious and have to be restrained from their viciousness.” This belief about the inherent tendency for violence in all humans seems to be the cornerstone of Lee’s political understanding and the Singaporean form of governance: since humans are vicious, and they can easily bring themselves to harm and kill others of their species, it is perfectly ok to force them into enclosures and monitor their every move.

Sadly, this idea seems to have become the guiding spirit of many political leaders and people around the world. Because, by translating his belief into actions, and by backing those actions with stellar results, Lee not only provided ammunition for tyrants and dictators to defend themselves, but also discredited what might be the greatest philosophical and political achievement of humanity: the unquestionable supremacy granted to democratic institutions and values.

Wealth vs freedom

One cannot deny the fact that Lee made his country wealthy and his people rich; he must be credited with turning a bog into the financial centre of the world, brimming with bright skyscrapers, world-class graduates, and moneyed technocrats. But do his achievements prove the redundancy of democratic values and tenets of human rights?

They do not. We still have the examples of countries in Europe, especially the Nordic countries and Germany, to prove that a country can become a major economy without forfeiting the democratic rights of its citizens or colonising distant lands.

And this argument is pertinent especially for a country like Nepal, which is living in a constitutional limbo that many attribute to its affirmation of the democratic system. The praises that Lee the benevolent dictator garnered in our country after his death for his ability to get things done shows the exasperation that the Nepali people seem to have developed for the ever-chaotic and ever-irresolute democratic procedure. Lee’s medicine might work miracles for our country, but should we allow ourselves to be abused, shepherded, and caned like beasts by a dictator just for the sake of prosperity?

Devkota is with the Post’s features section

12.12°C Kathmandu

12.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)