Sun, Sep 28, 2025

Opinion

Preparing to adapt

Nepal needs an integrated, coordinated and targeted adaptation strategy for climate change

bookmark

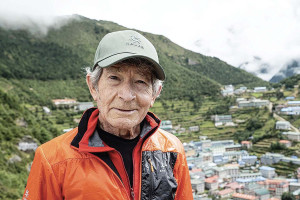

Madhav Karki

Published at : February 18, 2014

There is no doubt that the increasingly warming climate will have tremendous impacts on Nepali society. During the last few years, Nepal experienced more frequent extreme monsoon rainfalls—bringing devastating floods like in Darchula in 2013, Pokhara in 2012 and Koshi in 2008—than ever before. Small-scale droughts, glacial lake outburst floods, avalanches, landslides and slope failures are occurring more frequently every year. The repercussions of these changes on Nepal’s ecological security can be devastating. Accordingly, Nepal seems on track to face a future temperature rise of 1.2 degrees Celsius by 2030; 1.7 by 2050 and 3.0 by 2100, if the current emission trend is not arrested at the global level.

Massive scale adaptations

The growing impacts of climatic events will have serious implications on the carrying capacity of our river basins, watersheds and ecosystems as well as public and private infrastructures and assets. Nepal, therefore, has no option but to launch adaptation and disaster preparedness on a war footing. But is such a massive undertaking even possible? Finance is the least of the problems, with the lack of political will, an enabling leadership and coordinated implementation efforts as the major bottlenecks.

Given the multi-dimensional context of climate vulnerability—geo-physical, social and economic—Nepal needs to develop policies and raise heightened awareness on the need for an integrated, coordinated and targeted adaptation strategy. Given the highly diverse ecological, social, and economic situation of the country, simply copying adaptation plans from other developing countries will not make the country climate resilient. While local schemes such as community forestry have been successful in reducing the adverse impacts of environment degradation, unsustainable road building sprees and other haphazard development activities are causing land degradation and physical hazards.

Climate change is likely to exacerbate these risks on our hilly watersheds due to the enhanced hydrological cycle, which will consequently cause costly damage to our agriculture, ecosystem and physical infrastructure. Therefore, mainstreaming climate change risks into entire sectoral policies, plans, programmes and institutions has to be the foremost policy priority of the new government.

A collective response is needed from all government, non-government and private agencies to build resilience. One of the major challenges in the current adaptation plan of the government is the lack of a framework for mainstreaming climate change considerations in the programmes of all relevant ministries and agencies, thus eluding coordination. The main reason for this is dominance of bureaucratic and traditional mindsets, archaic institutions and a lack of clear political direction.

Ecosystem-based adaptation

Integrating Nepal’s river basins, ecosystems and watersheds into one system-based response will be key to sustainable adaptation and development. Currently, Nepal is piloting Ecosystem-based Adaptation (EbA), which provides a better framework for planning and implementing integrated adaptation. EbA operates on a ecosystem or landscape level and aims to increase resilience and decrease vulnerability by intervening with measures that enhance biodiversity and restore and regenerate vegetation. For a largely mountainous country like Nepal, EbA holds much promise since its framework is broad enough to accommodate our diverse social, economic and environmental needs. EbA first strengthens nature’s capacity to adapt to the changing climate and then builds on improved human and institutional capacity to reinforce natural resiliency.

Ecosystem management is a complex decision-making process, as it crosses administrative and political boundaries but we have nature to guide us in coordinating our activities. Our hill farmers have been practicing complex farming systems in harmony with the environment for ages. Therefore, effective climate adaptation will have to follow the natural boundary, ie, ecosystem, watershed or river basin. Building resilience on inherent natural capacity would be the most cost effective, quick and sustainable strategy.

Challenges ahead

There are of course challenges to institutionalising EbA in Nepal, one of which is that the costs of interventions largely fall on the people within the ecosystem but the benefits generated go to both insiders and outsiders, including across the border. Therefore, finding incentive measures to convince communities to practice ecosystem management activities is a real challenge. Yet another challenge is that the benefits generated through EbA activities are long-term while the costs incurred are immediate. Compensation mechanisms, such as Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES), will be necessary and need to involve all stakeholders, taking an ecosystem or watershed as a unit.

Nepal’s grinding poverty and food insecurity demands that both the ecosystem and the socioeconomic development agenda be pursued simultaneously. This means adaptation options that have the best economic, ecological and social rationale have better chances for the meaningful participation of people. Developing adaptation strategies for managing diverse ecosystems therefore requires a good understanding of how climate change impacts our societal, developmental and environmental features. Options that are based on thorough knowledge of local practices, current and future climate and non-climate hazards and risks and the people’s own vision for adaptation and development need to be given higher preference. Adaptation has to also consider social and gender equity aspects.

A climate resilient Nepal

Finally, Nepal’s traditional sectoral development approach makes EbA planning and implementation difficult. Planning based purely on administrative boundaries will not lead to sustainable adaptation. Once the country adopts a federal structure, new challenges and opportunities will emerge. Adaptation is a local agenda and needs constant input of knowledge, technology, finance and capacity enhancement, which decentralised structures have the potential to improve. However, in such decentralised systems, there is also a danger of imposing top-down measures that disenfranchise local communities, which will hinder adaptation.

Perhaps a constitutional provision that requires provinces to ensure community-approaches, ecosystem integrity and river basin/sub-basin wide coordination in development and environmental intervention might help Nepal better adapt to climate change. Here, the new Constituent Assembly members have a great responsibility to ensure that Nepal’s future development paradigm is based on a principle of sustainable development, which means that all units and levels of government have to ensure that their development activities ensure a balanced treatment of the environmental, social and economic pillars.

Karki is South Asia Chair of the IUCN Commission on Ecosystem Management

Editor's Picks

How misinformation fuelled panic during Gen Z uprising

At 86, Spanish Carlos Soria sets sights on Manaslu

She made history as first woman chief justice of Nepal. Now as PM

3 Gorkha youths killed in Gen Z protests, leaving families and dreams shattered

Nepal’s immunisation on the brink after vaccine stocks gutted in arsons

E-PAPER | September 28, 2025

×

18.72°C Kathmandu

18.72°C Kathmandu