National

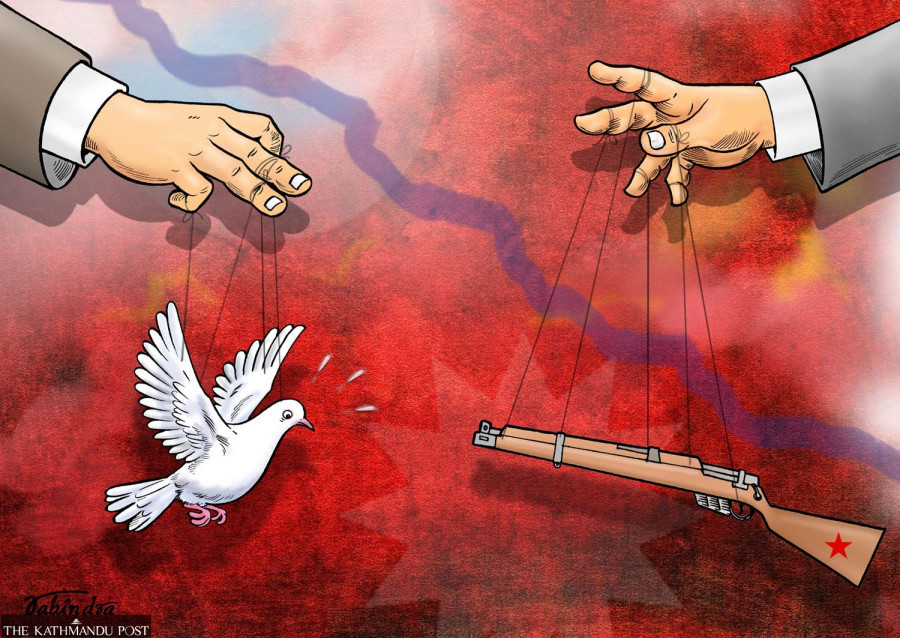

Peace deal into 17th year, yet no justice for victims

Thousands of victims of Nepal’s Maoist insurgency that ended in 2006 are still awaiting closure.

Binod Ghimire

On December 16, 2001, Sita Ram Tharu was sitting in a tea stall near his house in Manpur village in Bardiya district when a group of security personnel arrested him accusing him of being a Maoist.

Dozens of security personnel in combat fatigues with faces covered by bandanas took him away assuring his family that he would be brought back home after a brief inquiry. Twenty-two years later, the family is still waiting for his return.

“We were told that my father was taken to Chisapani barracks [Bhim Kali Company of Nepal Army in Bardiya district]. But nobody was allowed to see him. Later the army denied arresting him,” Manish Chaudhary, his son, told the Post. “Our family has spent over two decades searching for information on my father’s whereabouts. I would like to ask the government: how many more years does it want us to fight for justice?”

Unlike what the security personnel claimed while arresting him, Sita Ram, a farmer, had no direct connection with the Maoists. According to Manish, in that period, members of the indigenous Tharu community were often branded Maoist cadres and subjected to torture, forced disappearances, and even killings. Bardiya was one of the most affected districts during the Maoist insurgency and has the highest number of incidents of enforced disappearances among all the districts, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross.

On November 21, 2006, then CPN (Maoist) and then prime minister Girija Prasad Koirala signed the historic Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which brought the warring party to mainstream politics. Through the deal, the government and the Maoist party also agreed to provide justice to all the victims of the insurgency.

However, even as the country marks the 17th anniversary of the deal on Tuesday, not a single victim has got justice. Thousands like Manish continue to fight for it.

“Let alone get justice, there is no proper law in place even today. And there is no hope for justice in the near future,” Gopal Bahadur Shah, chairperson of the Conflict Victims National Network who was tortured and displaced by the Maoists, told the Post.

Despite pledges by successive governments to expedite the transitional justice process, there has been no progress in amending the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act. Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal and his predecessor Sher Bahadur Deuba both said amendment of the Act and appointment of office bearers in both the commissions were their topmost priority. However, the amendment bill still remains disputed.

After spending five months in discussions, a sub-committee under the Law, Justice and Human Rights Committee of the House of Representatives on October 10 presented an incomplete report to the committee after failing to forge consensus on four issues. Following differences among political parties, the subcommittee has been unable to decide on whether to classify murder as a serious violation of human rights, hence becoming a non-amnestiable offence. The current bill lists only ‘cruel murder’ as a serious violation of human rights, drawing criticism from various quarters.

Despite long discussions, the sub-committee couldn’t decide whether to categorise arbitrary killings or all killings except those that occurred in clashes as serious violation of human rights. Similarly, the committee also could not decide what happens in case the victims of human rights violations refuse to reconcile. The sub-committee also could not come to an agreement on addressing the concerns of those indirectly affected by the conflict.

Several people have lost their lives and scores of others have been injured in the landmines planted during the insurgency, but the transitional justice process has failed to accommodate them. Also, cross-party lawmakers could not find consensus on reducing sentencing. Though there is an agreement that the penalty for the perpetrators who cooperate in the investigation can be reduced, they have yet to agree on the amount of reduction.

“We tried our best to forge a consensus, but failed. I don’t think the House committee can finalise the bill without a broader consensus among major parties,” Santosh Pariyar, chief whip of the Rastriya Swatantra Party, who is also a member of the committee, told the Post. “It is the primary responsibility of the government to make an earnest effort to bring all the parties together. I haven’t seen that happen.”

He, however, says the message of the United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres during his Nepal visit a few weeks back that the transitional justice should be victim-centric has put some pressure on the political parties to work seriously towards conclusion of the process.

In his address to the joint meeting of federal parliament on October 21, Guterres said the transitional justice process can only succeed if it is inclusive, comprehensive and has victims at its heart. That means “... it centres on truth and reparations but also justice. When women participate fully. And when all victims of human rights violations can find meaningful redress,” he had said.

“The United Nations stands ready to support you to develop a process that meets international standards, your Supreme Court’s rulings, and the needs of victims—and to put it into practice.”

The victims have accused successive governments of lack of seriousness on relief while also not revealing the truth behind the crimes as well as of failing to take legal action against the perpetrators. “I didn’t get to study well as I lost my father in my infancy. It would have been a great help if there was a job opportunity,” said Manish. “But I don't think the government is bothered about our plight.”

23.88°C Kathmandu

23.88°C Kathmandu