National

A song that took the country by storm

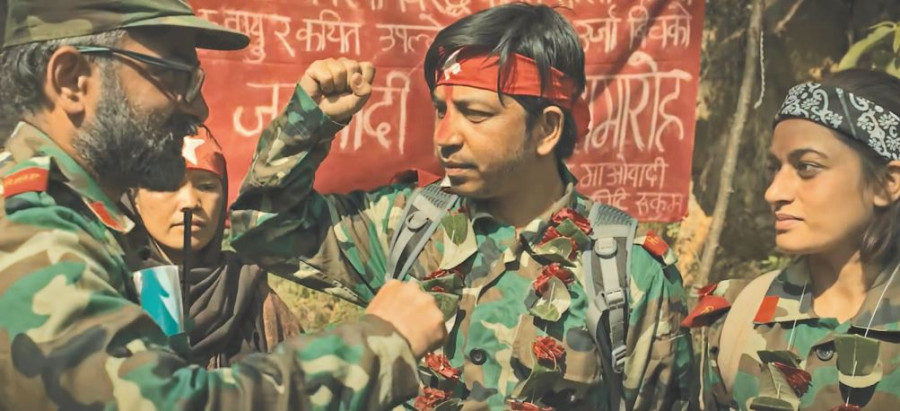

Prakash Saput’s music video portrays the disillusionment of former Maoist fighters while depicting the real story of society, observers say.

Anup Ojha

A Nepali song released on Friday, which has attracted more than 5.3 million views till Monday evening, has over the last four days prompted a fierce debate over the Maoist “people’s war”, with social media platforms flooded with comments for and against.

Prakash Saput’s new music video titled “Pir”—which means sorrow in Nepali—tells the story of the plight of a couple that fought as Maoist fighters but now struggles to eke out a living, even as those who led the war live lavish and comfortable lives.

While the Maoists have taken exception to the song, calling it misleading and saying that it undermines the well-intended “people’s war”, others say Saput has shown the mirror to the Maoist leadership who flagrantly abandoned the foot soldiers who made the fundamental pillars of the armed insurgency.

Some Maoist members have even sent warnings to pull down the video from YouTube.

Observers say while Saput’s song depicts the real picture of society, there are some key elements that are completely lost in the social media cacophony.

Lokraj Baral, a former professor of political science at the Tribhuvan University, says the problem with the Maoist Centre leadership is that they could not fulfil what they had promised during the time of the armed insurgency.

“They talked about many things that were not achievable to make people join the war,” said Baral. “Hence there is dissatisfaction among many former fighters.”

There is one section that has always loathed the Maoist war and now is riding on the song to deride the Maoists and their armed struggle.

Observers say the Maoist war’s contribution in bringing socio political transformation in Nepali society cannot be ignored, but the way the leadership was co-opted after the peace deal and became part of the same parliamentary system that they once fought against is something they should introspect.

“The Maoists deserve credit for setting the agenda of republicanism. Inclusivity is one key issue that they raised fiercely,” said Baral. “But over the years, they have lost direction. They don’t even have the ideological foundation now.”

The 16-minute video has a straightforward story.

A couple, both former Maoist fighters, lives in Kathmandu with their small daughter. The struggle is immense. The husband owns a small meat shop that barely earns enough to sustain the family.

The wife, frustrated at the husband’s meagre income, decides to go for foreign employment. They discuss what they achieved by participating in the bloody war—both had received bullets while fighting. The husband limps; the wife has a big scar of a wound on her right ribs.

“Did we not take the bullets in the name of the country and the people?” the wife asks. “What did we achieve?”

“Ganatantra [republic],” the husband responds, keeping his calm.

The wife ultimately goes abroad, leaving the daughter with her husband. About three months later, the husband learns she has been trapped in the foreign land and is pleading for help. He reaches out to his former comrade, who is now a minister. The minister, however, not only ignores his pleas but even refuses to recognise him.

He decides to leave the country. The daughter then leaves him perplexed when she asks: “What does a country mean?”

One dramatic element that Saput has inserted in the story is: the husband one day, at the persuasion of his friend, goes to a sex worker, only to find she is also a former Maoist fighter.

Maoist members have taken umbrage at it, saying the singer has crossed the boundary of creativity and insulted former women fighters by depicting them as sex workers.

“The music video that depicts women combatants who fought for the country’s political transformation as characterless is unacceptable,” Suman Devkota, coordinator of the Young Communist League Nepal, youth wing of the CPN (Maoist Centre), wrote on Facebook. “I would like to request Saput to take the video down.”

Satya Pahadi, a Central Committee member of the Maoist Centre, said on a Facebook Post that the singer has disrespected the bravery, courage and sacrifice of Maoist fighters.

“The singer has not only committed violence against those women who participated in the war but also all the women,” she posted. “This is not only condemnable but also liable to legal action.”

Baburam Bhattarai, who is considered a key architect of the Maoist insurgency, however, took to Twitter to urge all not to threaten the singer.

“Being a former leader of the people’s war, I reserve the right to comment on Saput’s song. There is nothing to feel offended about,” reads Bhattarai’s tweet. “The song does not oppose the people’s war. It has depicted the pain of the incomplete revolution. There is a need to take the revolution forward in a new way. Why threaten the creator of the song?”

Amid the intense debate over the song, Saput, the singer, on Monday issued a statement.

“I have only tried to portray a common man’s expectations from the state and the rejection they receive,” Saput wrote on Facebook. “I have only tried to say that the country witnessed the change because of the people’s war but people’s situation could not improve.”

“I have tried to show the growing gap between the comrades who once fought for equality,” he added. “But are not these the same issues which have been shown on television programmes… written and read in newspapers…?”

According to Saput, he has created the characters from what he learned from former Maoist fighters who he interacted with during his four years of singing at a restaurant.

“Many of those I came across who would sing, play musical instruments, cook and serve were Maoist fighters,” he said.

Responding to calls to remove the video, Saput has said such an act would devalue the insurgency, movements, republicanism and freedom of speech.

“I am an artist and my creations are my voice,” he said. “Controversy is not in my nature. Nor is it my strength.”

Even 16 years after the signing of the peace deal, the debate continues—whether the “people’s war” indeed was needed or was it just an outcome of adventurism of some communist leaders who romanticised revolution.

While top Maoist leaders continue to justify the war, they admit that they have failed to maintain the momentum to keep the revolutionary agenda alive.

Mumaram Khanal, who quit the Maoist party about two decades ago, says the dreams sold by those who call themselves revolutionaries are difficult to achieve.

“This has happened with the Nepali Congress and the CPN-UML as well,” Khanal told the Post. “The Maoist war issue keeps recurring and is talked about a lot because this is the latest in Nepal’s political history.”

According to Khanal, after joining mainstream politics, Maoist leaders were co-opted.

“Maoists were radical in their literature but that does not work in real life and they need to become pragmatic in politics. Therefore there appears to be a contradiction,” he said.

The main question is, said Jhalak Subedi, a political commentator, whether the Maoist leaders are working to ensure that they are accountable to the people who participated in the revolution and those at the grassroots.

“After the political change, one section of the Maoist party has drastically changed their lifestyles, while those who sacrificed a lot were left high and dry,” said Subedi, who has followed leftist politics for decades. “The problem lies with those who have changed, not with those who are at the receiving end and who are demanding accountability.”

8.79°C Kathmandu

8.79°C Kathmandu.jpg)