National

Verdict ahead of parliamentary hearing raises multiple questions

Experts say the Supreme Court saying Nahakul Subedi is qualified for the post of justice before parliamentary hearing threatens the principle of separation of powers.

Binod Ghimire

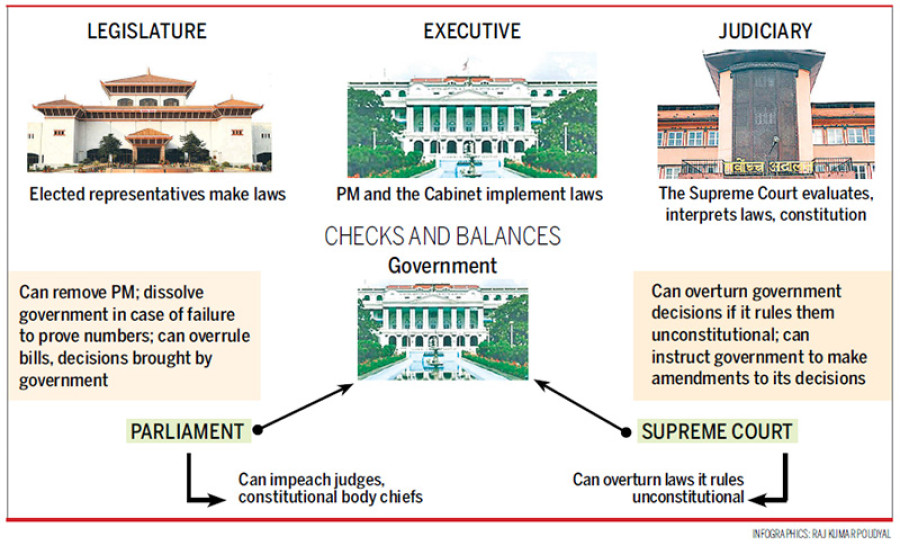

A recent Supreme Court decision has put a spotlight, once again, on how the principle of checks and balances is facing a threat in Nepal.

The Supreme Court said on Monday that a nominee is “qualified” to become a justice at the top court, days before his appearance at the parliamentary hearing committee, which constitutionally is the rightful authority to endorse or reject the nomination made by the Judicial Council.

The Judicial Council on March 12 recommended Nahakul Subedi, along with Kumar Chudal, both High Court chief judges, for appointment as justices of the Supreme Court.

As per the constitutional provisions that require such nominees to face parliamentary hearings, they are scheduled to appear before the committee on Friday.

But advocate Surendra Bhandari on March 27 challenged the Judicial Council decision to recommend Subedi as the Supreme Court justice, saying he does not meet the qualification as prescribed by the constitution to hold the post. Bhandari also demanded that the recommendation be quashed.

Bhandari cited Article 129 (5) of the constitution, which says “a candidate for the post of Supreme Court justice needs to have either 12 years of experience of working as a first class Gazetted officer or a higher post in the judicial service for at least 12 years or five years of experience as a judge or chief judge of the High Court.”

Subedi, who took his appointment as a joint-secretary at the Judicial Council in August 2007, was appointed a judge on January 4, 2018. When he was appointed High Court chief judge, he had the total experience of a little over 10 years. When he was nominated for Supreme Court justice on March 12, he had completed only a little over three years as a High Court judge.

Bhandari has argued in his petition that the constitution explicitly says for a person to qualify to become a Supreme Court justice, he or she must have worked for 12 years as first class officer or five years as the High Court chief. Bhandari also argued that a Chief Judge is not counted as an employee of the Nepal government, as it is a special position.

But while passing the verdict, a single bench of Justice Tej Bahadur KC said on Monday that Subedi qualifies to assume office as a Supreme Court justice as his “combined experience as gazetted first class officer and High Court chief judge” exceeds 12 years, the minimum qualification prescribed by the constitution.

Experts and analysts say Nepal’s key state agencies, which are supposed to complement each other, are making attempts to override each other, endangering the very principle of separation of powers which is key to a functioning democracy. And the verdict on Subedi’s case also reeks of judicial activism, according to them.

“This verdict is yet another example of judicial arbitrariness,” said senior advocate Dinesh Tripathi. “The verdict is also a blatant attack on the constitution.”

According to Tripathi, the way the judiciary is passing verdicts, it looks like the agency that is the ultimate arbiter of the constitution has itself emerged as a threat to the constitution.

The Supreme Court lately has been at centre stage, especially since December 20 when Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli dissolved the House. Its February 23 decision to overturn Oli’s House dissolution and ask authorities to call the House session within 13 days while earned praises for him, its March 7 decision to scrap the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) and revive the CPN-UML and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) attracted widespread opprobrium.

Critics say by “giving” more than what the petitioner had demanded in the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) case–that scrapping the party and ordering the revival of the UML and the Maoist Centre–was a judicial overreach.

According to experts, now by passing a verdict on Subedi’s case, labelling him “qualified” for the post, long before the parliamentary hearing committee could do its job, the Supreme Court once again has overstepped the limits of its jurisdiction.

“It looks the sole motive of issuing the verdict just a few days before the parliamentary hearing is intended to influence the hearing committee,” said Mohan Lal Acharya, an advocate who has served in the past as an adviser to the Constituent Assembly. “The verdict has put the parliamentary hearing committee in a fix. Rejecting Subedi will be tantamount to going against the Supreme Court verdict.”

Nepal’s constitution has provisioned parliamentary hearing of some key nominations to vet the recommendations by the Constitutional Council, the Cabinet and the Judicial Council and reject the recommendations if the hearing committee believes the proposed individuals cannot hold the position or cannot discharge their duties effectively.

Article 292 of the Constitution of Nepal says parliamentary hearing shall be conducted as to appointments to the offices of the chief justice and justices of the Supreme Court, members of the Judicial Council, chiefs and members of constitutional bodies, who are appointed on the recommendation of the Constitutional Council under the constitution, and to the offices of ambassadors, as provided for in the federal law.

For the purpose of hearing, the constitution has envisioned a 15-member hearing committee consisting of members from the House of Representatives and the National Assembly.

Experts have also questioned the timing of the verdict on Subedi’s case. According to them, the Supreme Court’s some of the verdicts in recent months have come at such a time that they have played a crucial role in changing the entire political landscape.

The Supreme Court verdict to scrap the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) and revive the UML and the Maoist Centre came on March 7, hours before the meeting of the House after it was revived on February 23. The case against the Election Commission awarding the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) name to Oli and Pushpa Kamal Dahal had been pending for nearly three years.

Rajendra Shrestha, a member of the committee from the Janata Samajbadi Party, says committee members know Subedi doesn’t meet the qualification to become a justice but he cannot say if the committee dares to act against the Supreme Court verdict.

According to Shrestha, the judiciary’s role should be towards giving a way out to the deadlock by interpreting the constitution, but it is making things more complicated.

Days before the Supreme Court labelled Subedi as qualified to become a justice, the Supreme Court Bar too had questioned the Judicial Council’s decision to nominate Subedi as justice, saying he does not meet the qualifications prescribed by the constitution. The Supreme Court Bar said that Subedi used the position of the chief registrar as a ladder to become Supreme Court justice. It said that its serious attention had been drawn to the decision to nominate unqualified persons when there are other qualified chief judges and judges for the post.

Subedi is the first person to hold the post of chief registrar. Before him, there was no post called chief registrar at the Supreme Court. The position was created during the tenure of former chief justice Gopal Parajuli, a close relative of Subedi.

The Parajuli-led Judicial Council in January 2018 had picked Subedi as chief judge.

Justice KC in his verdict has said it was unjustified on the part of the Supreme Court Bar to raise the qualification issue.

Experts on constitutional matters disagree and they say the question is not about an individual but is about the rule of law, the principle of separation of powers and checks and balances.

“The Supreme Court misinterpreted the constitution and encroached upon the jurisdiction of the legislature,” said Tripathi.

The court passed the verdict even without issuing a show cause notice, a practice which it usually follows.

The Supreme Court getting into a confrontational mode with other key agencies like the legislature is not a good sign for democracy, according to experts.

“However, I still believe the hearing committee would take an appropriate decision to correct the wrong decision of the Supreme Court,” said Tripathi. “The parliamentary committee’s jurisdiction is wide. It doesn’t just check the constitutionality but also the appropriateness of appointments.”

The question, however, remains what if the person in question moves the court if the hearing committee rejects his nomination. The judiciary and the legislature will once again be at loggerheads.

“It looks like the country’s politics will now be defined by the judiciary, given the recent verdicts the Supreme Court has passed,” Shrestha, the hearing committee member, told the Post. “Passing a verdict on a matter which should have been constitutionally dealt with by the parliamentary hearing committee is out and out breach of the principle of separation of powers.”

27.41°C Kathmandu

27.41°C Kathmandu