National

Hundreds of young, healthy Nepalis die sudden deaths in foreign lands. No one knows what’s killing them

Otherwise healthy men in the prime of life suffering cardiac arrests do not constitute ‘natural deaths’, say rights activists.

Chandan Kumar Mandal

Santosh Kumar Mandal had been working in Malaysia for three years as an industrial worker in a toy factory when his family began to ask him to come back. His father, Shani Lal, wanted to get Santosh married.

“We wanted him to come back, get married and settle down,” said Shani Lal. “Then, he could decide whether to go abroad again.”

But the Morang native refused; he wanted to work some more so he extended his contract by a year. On October 18 last year, before he left for work, Mandal reported a sharp pain in his chest. His fellow workers took him to the hospital, but Mandal died on a hospital bench, waiting for the doctor.

His friends and family were shocked by his sudden death. At 24, Mandal was young and in the prime of his life. As an industrial worker, he got enough exercise and had never reported any health issues. But he had died, suddenly, of a heart attack, according to the death certificate.

“There was no one as healthy and strongly built as my son,” said Shani Lal, holding up a photo of Santosh. “He had never even fallen sick when he was with us. How could he die of a heart attack?”

The way Mandal died is how many Nepali workers in foreign lands die--suddenly, without explanation or any prior signs. Young men and women, often with no previous health ailments are dying abroad at alarming rates--an average of two every day--and all too often, no one knows how or why they died.

The same fate befell Indra Bahadur Chaudhary from Bara last year. Chaudhary had decided to work abroad after seeing his friends leaving for the Gulf and Malaysia. When he first left for Malaysia, he was only 17 or 18, recalled his father Ram Prasad Chaudhary, a retired police officer.

“Going abroad is in fashion and my son followed the trend,” Ram Prasad told the Post over the phone from his village in Bara. “I couldn’t stop him. There weren’t any jobs to be had at home and he said he would earn money and come back.”

What started as a one-time trip to Malaysia in order to make enough to start a business of his own turned into multiple stints abroad. He went to Malaysia for the third time in November 2017, paying over Rs100,000. He was making a decent wage—slightly above Rs30,000 per month, according to his father.

But Chaudhary would never come back. Like Mandal, 30-year-old Chaudhary too collapsed while leaving for work. He died of a “coronary artery occlusion by atheroma”, according to the death certificate issued by the Malaysian authorities. A coronary artery occlusion by atheroma is the partial or complete obstruction of blood flow due to a buildup of material inside an artery.

“I had never imagined that he would die of a heart attack,” said Ram Prasad. “He was healthy and he had no health issues as such. He left and never came back.”

Dying in large numbers

Every year, tens of thousands of Nepalis leave the country for foreign shores, hoping for better opportunities and a livelihood for themselves and their families back home. They send back billions in remittance, which has continued to fuel the Nepali economy for years now. But many of these Nepali workers never make it back home alive--every year, thousands make the journey home in a coffin.

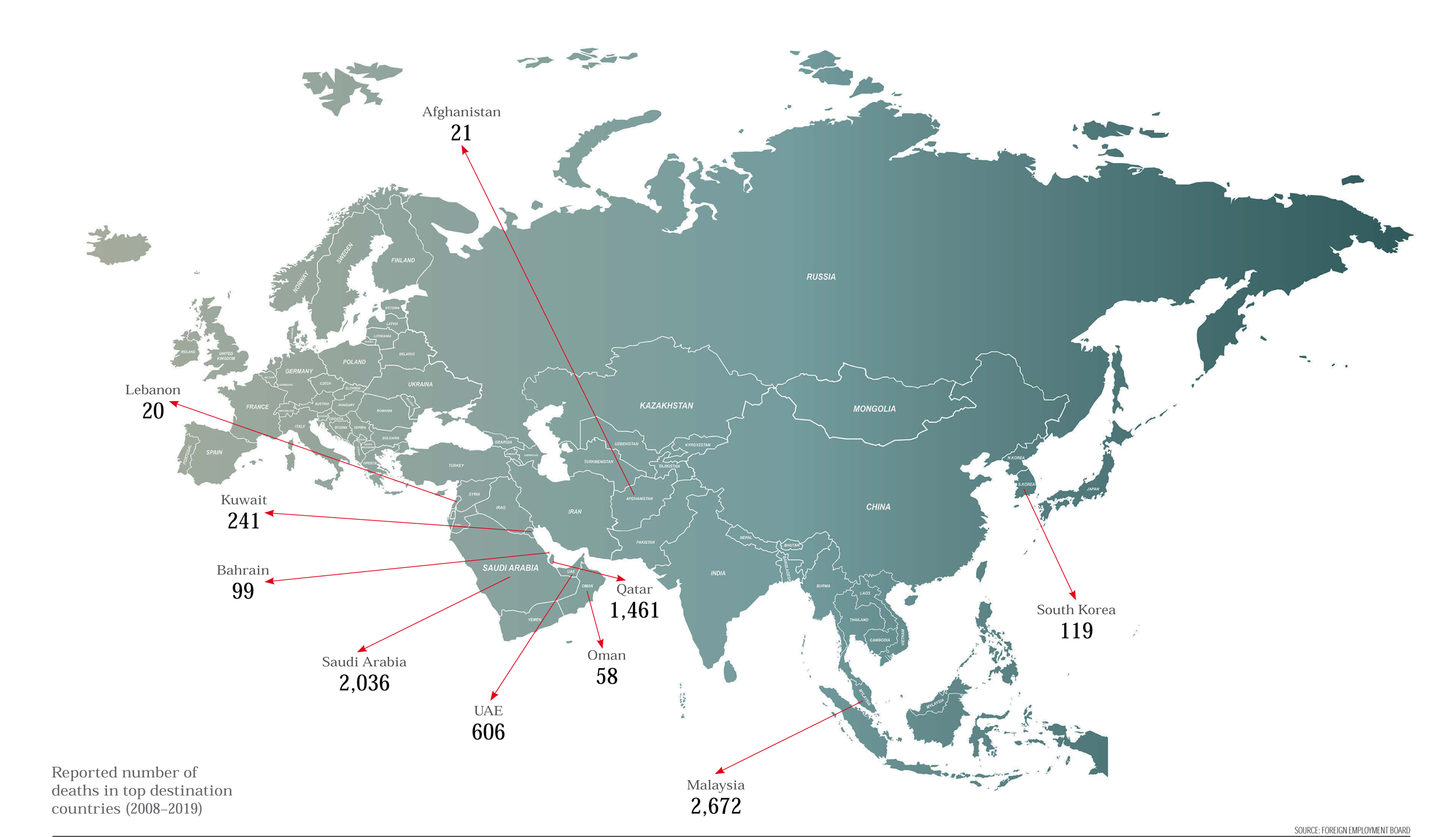

In the last 11 years, a total of 7,467 Nepalis have died while working abroad as migrant workers, according to data from the Foreign Employment Board, the government body that works for the welfare of migrant workers.

This number, however, is estimated to be significantly larger, as the Board’s statistics only enumerates those migrant workers whose families received compensation for deaths. Not all deaths are compensated as the Board requires a labour permit and there are estimated to be thousands of undocumented Nepalis in foreign lands who go abroad through various illegal channels.

“Nepali workers do not deserve to die like this abroad. People dying in such numbers can never be a normal phenomenon,” said Barun Ghimire, a human rights lawyer and programme manager at the Law and Policy Forum for Social Justice, an organisation that works on migrant rights issues. “Had they been dying while fighting a war, we could say they died in a brutal war. If workers from other countries were dying at the same rate then it might make some kind of sense. But Nepali workers are dying at a higher rate than workers from other countries.”

Most Nepali deaths have been reported in the Gulf countries like Qatar, where thousands of migrant workers are building stadiums for the 2022 FIFA World Cup, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab of Emirates, and Kuwait. There are also many deaths in Malaysia, which hosts the largest number of Nepali migrants, and South Korea.

A majority of these deaths are sudden, meaning they occur in migrants with no prior history of disease or illness. But despite the fact that these deaths occur unexpectedly in young men and women, and at a startlingly high rate, they are often termed “natural deaths”.

What is killing Nepalis abroad?

The Centre for Migration and International Relations, an organisation housed in the peaceful inner lanes of Kathmandu’s Buddhanagar, provides all kinds of legal and paralegal support to the families of migrant workers in case of their deaths, including assisting in the repatriation of dead bodies and the preparation of official documentation. Every month, the centre deals with 15-20 deaths.

According to the centre, these deaths are broadly categorised into cardiac arrest, heart attack, murder, natural death, suicide, traffic accident, workplace accident, other or unidentified, and ‘under investigation’, which are categories maintained by government records. These categories in turn are generated based on documents—police and medical reports--issued by the local authority that accompanies the dead bodies.

“But there is room for investigation,” said Yubaraj Nepal, director of the Centre for Migration and International Relations. “These deaths are basically categorised as per the death certificates. Most deaths appear to fall into the same handful of causes.”

Government records show that a majority of Nepalis die due to heart-related diseases—heart attack and cardiac arrest—workplace and traffic accidents, suicide, and other reasons. But a large number of Nepalis also die due to unknown reasons, which are then clubbed into ambiguous categories like natural deaths, other, and under investigation.

In the last fiscal year alone, over 100 deaths were presented as ‘other’ (44), ‘unknown’ (29), and ‘under investigation’ (29).

The ambiguity generated by this classification of deaths has even been pointed out by the government’s annual report—Labour Migration For Employment: Status Report 2015-2016 and 2016-2017—the latest in the series. According to the report, the classification of the cause of death reflects a significant ‘grey area’.

Sometimes, dead bodies aren’t accompanied by death certificates. According to Nepal, while most bodies from the Gulf Countries come back with death certificates and medical reports, reports from Malaysia sometimes arrive without such documentation, as an investigation is ongoing. These reports are generally forwarded later, but by then, they’ve already been entered into the ‘unknown’ or ‘under investigation’ category.

But in Nepal’s five years working with migrant workers, he’s found that death certificates are not always credible. In most cases, the organisation tries to reach out to the deceased worker's employer, their relatives or Nepali colleagues in the same company. And there are times when reports from friends and colleagues contradict the death report.

“There have been differences reported between the two sides, raising questions about the authenticity and credibility of the death certificates,” said Nepal. “As we don’t have any mechanism to check how authentic these reports are, we have to accept the cause of death mentioned in the documents.”

In between natural and unnatural deaths

Nepal’s labour migration has been historically male-dominated but those migrating are overwhelmingly from an age group that is not only economically active but also healthy. But these are the same people who are dying ‘natural deaths’, a category that appears rather unnatural for an age-group that is between 20 and 44 years of age.

According to the Labour Migration Status Report, among the 5,892 migrants who died between 2008-09 and 2016-17, 1,351, or 23 percent, died ‘natural deaths’.

“These deaths are not natural, as those who’re dying are around 35 years of age and they had been certified as healthy before they left Nepal,” said Ghimire, the human rights lawyer. “What is a natural death? People are dying in Nepal as well due to road accidents and cardiac arrest but we need to look into the patterns and proportion. When people of that age group are dying ‘natural deaths’, that is problematic and contentious.”

In the last two fiscal years, 126 and 136 more deaths have been categorised as natural, according to government data.

It is possible that migrant workers are suffering cardiac arrests and dying, given their work conditions, especially in countries in the Middle East. According to Dr Meghnath Dhimal, chief research officer at the government's Nepal Health Research Council, deaths in the Gulf countries can be attributed to high temperatures and workers not drinking enough water, even when they are working under the scorching sun.

But there are just too many such deaths, especially given that these migrants were properly checked before departure, said Ghimire.

Every migrant worker has to pass a medical test before leaving for jobs abroad. Medical examinations are also conducted once they reach their destinations.

“Migrants should actually be healthier, as they need to pass stringent medical tests,” said Anurag Devkota, who is also a human rights lawyer. “They are declared medically fit by the government. So the high number of deaths does raise suspicions.”

But given the state of the Nepali migrant labour industry, the effectiveness and authenticity of medical examinations and certificates issued by health institutions can raise questions.

“We also have to see how effective these health checkups are as they do not examine everything,” said Nepal, the director of the Centre for Migration and International Relations. “Sometimes, workers might have problems that were not detected during the medical test. Once they reach their destinations and start working under harsh conditions, these problems can exacerbate, leading to death.”

Dhimal of the health research council agrees.

“Health certificates are not detailed examinations,” he said. “They are only a check on whether the worker is physically fit or not suffering from diseases like tuberculosis.”

The mystery of ‘unknown’ deaths

Nepalis in foreign lands are not just dying ‘natural deaths’--they are also dying of unknown reasons. From 2008-09 to 2016-17, as many 921 deaths were classified as ‘other or unidentified causes’ and ‘under investigation’. In the last two fiscal years, 109 and 102 deaths were recorded under these categories. The government started maintaining data on the ‘under investigation’ category only three years ago.

The classifications of ‘other or unidentified cause’ and ‘under investigation’ themselves raise suspicions, as they are inconclusive and do not provide any kind of closure to families.

“When medically fit persons die of unknown reasons, families do not even get compensation,” said Anjali Shrestha, a programme officer with the Centre for Migration and International Relations, who deals with repatriation of dead bodies and their documentation. “It’s tough for families to accept this. Most of the time the heart beat stops, but that is ultimately the case in all deaths. There is no definition of unknown deaths, making it even more dubious.”

The government’s labour report itself raises doubts about these categorisations for two primary reasons.

“First, many categories under which the cause of death of a migrant worker is classified are ambiguous and coupled with the lack of information and they can lead to speculative conclusions that need further research,” states the Status Report. “Second, if the available information is taken at face value, then it suggests an emerging public health problem that needs deeper understanding, backed by systematic analysis and immediate intervention.”

The report urges an in-depth investigation into autopsies and medical records to better under the causes of migrant deaths. There have not been any governmental studies to explore the causes of deaths of Nepali workers abroad, but according to the Nepal Health Research Council’s Dhimal, the Council has formed a committee to conduct research in the sector of migration and health.

But as of now, neither the government, migrant organisations nor the media has attempted to try and figure out just what these unknown deaths are and why so many continue to die due to such mysterious reasons, said Ghimire.

“There must be some reason, like kidney failure or heart attack or anything else,” he said. “Unknown deaths or unidentified causes can be listed as the cause of death just because they do not fall into the list of causes maintained by the government.”

But mentioning of causes as unidentified only raises concerns about suspicious deaths in labour destination countries. Thereby, mentioning of natural causes and something as unidentified only raises suspicion on deaths of Nepali workers in foreign countries.

“We don’t know how they are dying. Who knows if they are also dying at the workplace. They are being taken to the hospital, which does not check where they died but how they died,” said Devkota. “Workplace deaths might account for remuneration and other insurances. There is no strong connection between employer and workers and also there are no trade unions, mainly in Gulf countries to speak on behalf of workers.”

According to government data, between 2008-09 and 2014-15, the highest number of ‘other or unidentified’ deaths occurred in Malaysia (546), followed by Qatar (140), and Saudi Arabia (34). Malaysia, which is the most popular destination for migrant Nepali labour, is also the deadliest country for with 2,154 deaths, or 36.56 percent of all deaths reported between 2008-09 and 2016-17.

Malaysia also reports the highest number of unidentified deaths. Often, death certificates are missing the cause of death, which leads to the death being categorised as ‘unknown’.

According to Nepal, the lawyer, Malaysia has a dubious track record when it comes to reporting deaths.

“Unknown causes of death in Malaysia are high because they do not have an effective investigation process,” said Nepal. “They send dead bodies without mentioning anything on the death report. Even when the cause of death is mentioned, we have found contradictory evidence on the bodies.”

In such cases, where the cause of death is suspicious, applications can be filed with the Foreign Ministry’s Department of Consular Services, which coordinates with Nepali missions abroad to repatriate dead bodies. But there is often no response from foreign authorities. Cases that are marked ‘under investigation’ often never get resolved.

“We can not always keep these deaths as unknown. The family must know,” said Nepal. “These deaths are neither investigated nor are there post mortem reports. Nepali embassies are poorly resourced but they can at least take the initiative to investigate deaths of their citizens.”

The first step to finding out the cause of death in such cases is to conduct a post-mortem, say labour rights activists. Forensic tests can also be conducted based on the evidence collected.

Two migrant rights organisations—the Law and Policy Forum for Social Justice and Pourakhi Nepal—had even filed a case at the Supreme Court demanding that an investigation be conducted into the unidentified causes of death.

Responding to the petition, earlier this year, in January, the Supreme Court issued a mandamus order against the concerned authorities, including the Nepal government, Labour Ministry, Department of Foreign Employment and Foreign Employment Board, to conduct investigations into unknown causes of death. The court asked the government to abide by provisions regarding minimisation of the risk of death to migrant workers, a compulsory post-mortem in case of natural or sudden deaths, and insurance and compensation.

“The family has the right to know how their loved ones died,” said Devkota, one of the lawyers who argued the case at the Supreme Court.”

But according to migrant rights activists, there is a benefit for employers to not identify causes of death, or categorise them as natural--they don’t have to pay compensation.

“In Qatar, for instance, a natural death does not require any medical investigation,” said Devkota. “If there are hazardous or suspicious deaths, then they are accountable for insurance payments that can reach as high as $80,000.”

According to lawyers, it is the responsibility of the governments of both countries, as well as the employer, to conduct post-mortems. But it is the Nepal government that needs to make sure that such an investigation is done.

“A post-mortem is also required because there have been reports of organ theft from the dead bodies of Sri Lankan migrant workers,” said Ghimire, who also argued the case. “Causes of deaths should be made public for two reasons—closure to the family and knowledge that could help minimise or prevent such deaths in the future.”

If suspicious deaths are investigated in Nepal, it is the responsibility of the Nepali state to ensure that such deaths are investigated in foreign lands as well, say activists.

“A mandatory post-mortem will help us find the real cause of death,” said Devkota. “If we had done this long ago, we might have an understanding of why these deaths continue to occur and find ways to prevent them from happening. Sadly, we had to wait for hundreds to die.”

Low and middle-income countries like Nepal do not have practice of investigating deaths, with most categorised as natural deaths, according to Dhimal.

“Only suspicious cases are further investigated,” said Dhimal. “But since the deaths of migrant workers is a crucial issue, there should be post-mortems and causes of deaths should be specified.”

For families, a sudden or unknown death is a wound that festers, leading them to wonder what could have been.

In Bara, Indra Bahadur Chaudhary’s family has been struggling to move on.

“There should be an investigation into all the deaths of migrant workers abroad. I keep wondering what killed my son,” said Ram Prasad. “I still cannot believe he died of a heart attack.”

13.25°C Kathmandu

13.25°C Kathmandu