National

Physically punishing students is ineffective, harmful and illegal but teachers continue to do it

Many school teachers, and even parents, still believe that physically disciplining students is sometimes necessary.

Binod Ghimire

It was time for morning assembly at the Bagmati Community School in Barahathawa, a small village to the east of Sarlahi. Students had lined up in orderly rows and were performing their morning prayers when Mahendra Prasad Yadav, the school’s headmaster, rushed towards them and began beating them with a stick. Yadav’s rationale: their prayers weren’t sincere enough.

Five students from grades one to three were injured, with bruises across their bodies. But it was 10-year-old Sanjeeb Sahani, a third grader, who suffered the most and fell unconscious. Sahani, who had always had a weak physical constitution, had to be hospitalised for two days, his parents said. Yadav had struck Sahani with the stick at least five or six times, which knocked him out.

Nepal was the first country in South Asia to criminalise corporal punishment, and in 2006, the Supreme Court issued a ruling asking the government to pursue appropriate and effective measures to prevent physical punishment as well as the cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment of children. But despite legal frameworks, teachers across the country continue to mete out inhuman levels of punishment to their students, beating them with fists, kicks, sticks and even the dreaded sisnu (stinging nettles).

The morning of June 17 wasn’t the first time Yadav had laid his hands on students. Parents and students who spoke to the Post said that beating children was part of his ‘teaching style’.

“He beat us regularly, often with a big bamboo stick,” Sahani said in an interview with the Post.

Parents were well aware of Yadav’s propensity towards violence, but as most families were poor, they didn’t dare protest his treatment. Yadav, as the headmaster, was the highest authority at the school and even if students and parents wanted to register a complaint, they had no one else to turn to. Most members of the community did not even know that corporal punishment was illegal and that victims could take legal action, according to Pramod, Sahani’s elder brother.

But when Sahani had to be hospitalised, the villagers finally had an opportunity to hold Yadav to account for his actions.

“Yadav’s brutality against the students would probably not have come out if Sanjeeb hadn’t fallen unconscious that day,” Pramod told the Post.

Dozens of villagers surrounded the school the next day, demanding that Yadav be disciplined. Confronted with parental rage, the police was forced to register a first information report.

Yadav, however, didn’t face any legal repercussions, and the case was settled with an agreement between him and the villagers. Yadav committed to stop beating children and vowed to ensure a ‘child friendly learning’ environment in the classroom. He also agreed to bear Sahani’s treatment costs.

Locals only agreed to recall their police complaint because Yadav’s absence from the school would affect teaching, said Ratna Bahadur Giri, chairperson of Ward No. 1 in Barahathawa.

“Yadav has been strictly informed that he will face severe consequences if he doesn’t correct himself,” Giri told the Post.

In the past month alone, at least five similar incidents have been reported from across the country. Over three dozen students have faced harsh physical punishment at the hands of their teachers.

In one especially egregious case, 14 students in Rolpa were beaten so badly by their teacher that five of them suffered severe injuries to their arms, with broken bones and ligament tears. The students, from Bhanu Basic School in Runti Gadhi, were beaten with a sal branch for showing up late to assembly.

Bimala Roka, an eighth grader from the school, said the teacher, Laxmi Pun, already had the branch in her hand when Roka arrived.

“She started beating us with the stick before I could say anything,” Roka told the Post. Appointed just a year ago, there had been numerous complaints about Pun, but she had faced no censure for her behaviour.

This time, police arrested Pun and registered an ‘offence against children’ case against her at the district court.

Speaking to the Post over the phone while out on bail, Pun said that she did not want to harm the students. “My only intention was to maintain discipline,” she said.

Legal defences

Pun’s answer is the justification most teachers provide when asked about them resorting to corporal punishment. According to children’s rights activists, physically punishing students wasn’t considered illegal, or even undesirable, for such a long time that both teachers and parents continue to believe that some level of physical disciplining is necessary at times.

At one time, Nepal’s laws supported this societal belief in physical punishment as sometimes unavoidable.

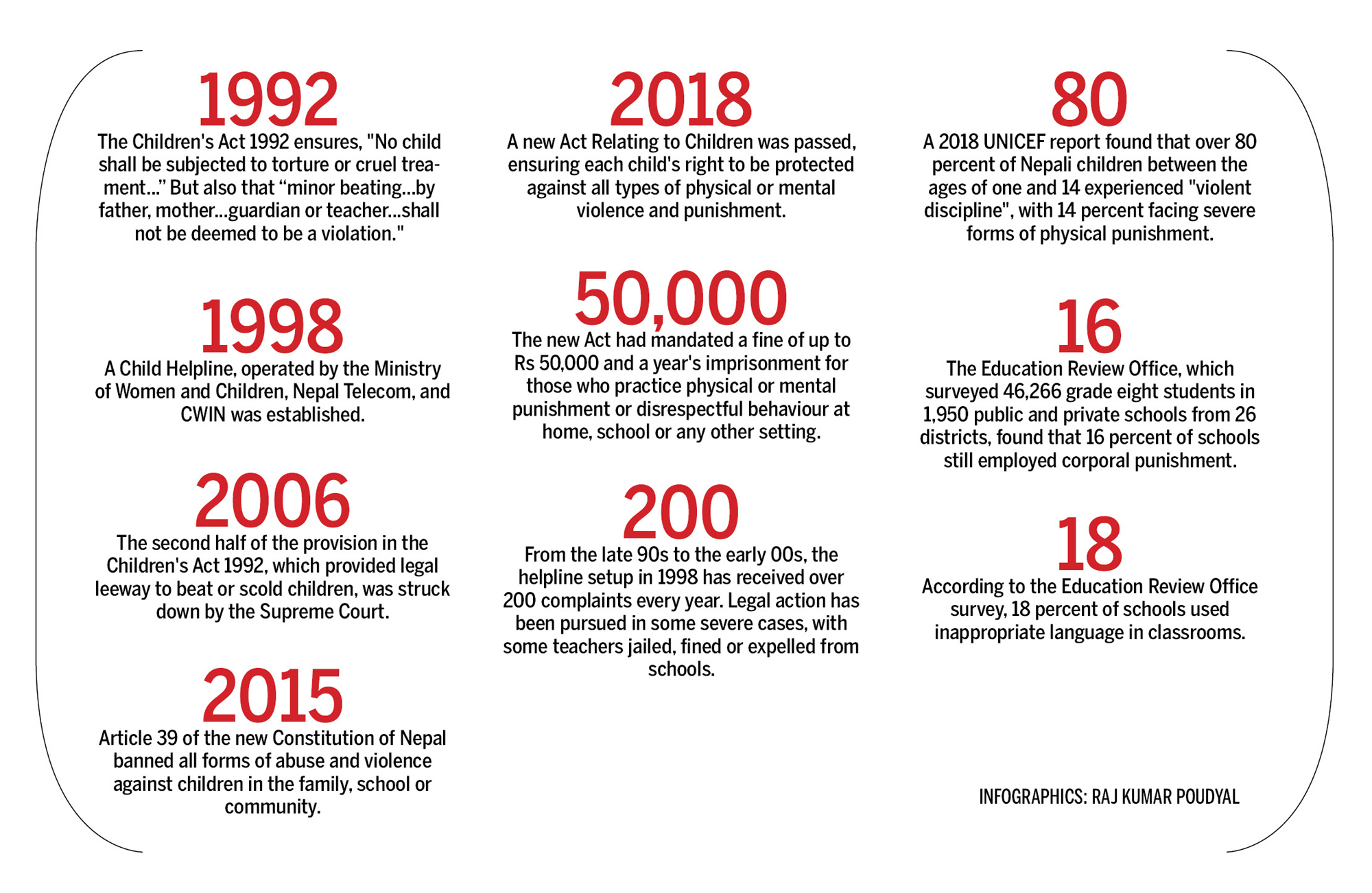

The Children’s Act 1992 says, “No child shall be subjected to torture or cruel treatment. Provided that, the act of scolding and minor beating to child by father, mother, member of the family, guardian or teacher for the interests of the child himself/herself shall not be deemed to be a violation of this section.”

The second half of this provision provided legal leeway to beat or scold, until the Supreme Court, in 2006, struck down the provision and asked the government take effective measures to prevent physical or mental punishment in any context.

However, it took over a decade for the government to come up with a new act that would comply with the court’s directive. Article 39 of the new constitution of Nepal, promulgated in 2015, banned all forms of abuse and violence against children in the family, school or community.

Finally, in September 2018, a new Act Relating to Children was passed, which ensured each child’s right to be protected against all types of physical or mental violence and punishment. It has mandated a fine of up to Rs 50,000 and a year’s imprisonment for those who practice physical or mental punishment or disrespectful behaviour at home, school or any other setting.

But despite legal provisions, many parents and guardians do not wish to take cases to court, activists say. The child will have to give statements to the police at least four times when the case is filed, which will only force them to relive their trauma. Often, as in the Barahathawa case, families prefer to settle cases out of court once the perpetrator admits their mistake and promises to stop.

“Nepalis are by nature forgiving so they prefer to compromise rather than pursue legal action,” said Tarak Dhital, former director of the Central Child Welfare Development Board, who has worked as a child rights advocate for over two decades. In this legal environment, advocacy and awareness are the most effective ways to reduce corporal punishment at school and at home, he believes.

Child rights activists, along with concerned families and teachers, have attempted to bring preventive measures to the children themselves. A Child Helpline, operated by the Ministry of Women and Children, Nepal Telecom, and Child Workers in Nepal (CWIN), an organisation that works for children’s rights, was established in 1998. The helpline, which can be reached by dialling 1098, has offices in Kathmandu, Biratnagar, Pokhara, Hetauda, Nepalgunj and Dhangadhi, which provide children with counselling services and support from the Nepal Police if necessary.

Last year, the helpline received complaints from 54 children who said that they had faced corporal punishments from teachers, relatives and parents. A majority of the cases—41—were from inside the Kathmandu Valley.

Thirty-one said that they had been mistreated by their teachers, five by their mothers, and four each by their fathers and relatives. One of the victims lost an eye while nine others had problems hearing.

This year, the helpline had received 25 complaints by the end of May, at a rate of five cases per month.

“One case a week is not a small figure, though the number of reported cases has gone down in recent years,” said Bharat Adhikari, child helpline manager. Adhikari, however, said that there are possibly many cases that go unreported.

In its initial days, from the late 1990s to the early 2000s, the helpline would receive over 200 complaints every year, said Adhikari. Legal action has been pursued in some severe cases, with some teachers jailed, fined or expelled from schools. However, cases of a minor nature are resolved without legal actions, after an agreement is reached between the two parties, officials said.

Despite such measures, rights activists say corporal punishment remains deeply rooted in society.

“Children often cannot speak for themselves, so adults always dominated them,” said Dhital. “Corporal punishment is an extreme manifestation of a mentality that the use of force is necesssary to maintain discipline.”

Long-term consequences

A 2018 report by UNICEF found that over 80 percent of Nepali children between the ages of one and 14 experienced “violent discipline”, with 14 percent facing severe forms of physical punishment. A vast majority of children undergo violence at the hands of those entrusted to take care of them, the report said.

Even government reports reveal that a significant number of children face punishment and bullying in both public and private schools. A report by the Education Review Office—which surveyed 46,266 grade eight students in 1,950 public and private schools from 26 districts—found that 16 percent of schools still employed corporal punishment and teachers from 18 percent of schools used inappropriate language in classrooms. The study further said that the performance of students who underwent such kinds of punishment was poorer than their classmates.

The UNICEF report also points out that the consequences of corporal punishment are wide ranging and long term in nature, including learning disabilities, behavioural disorders and depression. Suffering violence during childhood can even perpetuate an intergenerational cycle of violence, said the report.

Psychologists say corporal punishments can have long-lasting effects on children and that they negatively impact learning.

“Corporal punishment can reduce learning motivation while also hampering emotional development,” said Salik Ram Bhandari, a clinical psychologist. “Beating or scolding children in front of their classmates can also develop an inferiority complex, which can consequently weaken the child’s confidence.”

In some tragic instances, corporal punishment, directly or indirectly, has even led to death.

On June 22, Sameer Lunwa, a fifth grader from the Kalidevi Secondary School in Lalitpur, committed suicide on the grounds that he didn’t receive fair treatment in school and at home. In his suicide note, he had named three teachers who he said beat up boys. “The teachers were suspicious even when I was sick,” he wrote. “I therefore would like to leave this world.”

The police are investigating the case and have taken the teachers named by Lunwa into custody.

Such incidents are tragic, and, according to Dhital, they tend to occur more frequently in private rather than in public schools.

A majority of teachers in private schools are untrained, unlike public schools, which have trained teachers, Dhital said. Public school teachers are provided with sensitivity training where it is explicitly made clear that the performance of students can never improve in an environment that is full of fear. Over 95 percent of teachers in public schools undergo this training, according to data from the Ministry of Education’s Centre for Education and Human Resource Development.

A content analysis of media reports on corporal punishment by the welfare board showed that the media had reported 15 stories of corporal punishment in the last year, with 11 from private schools.

Smaller private schools don’t have the resources to hire trained teachers, and so, they take in teachers who lack experience, and pedagogical and behavioural skills, Dhital said.

Private school operators disagree with Dhital’s assessment, saying they do train their teachers. Private schools are just as serious about children’s rights and providing a positive learning environment, said Ritu Raj Sapkota, chairman of the National Private and Boarding Schools Association Nepal, an umbrella body of private schools.

“We understand that classrooms should be free from fear,” Sapkota told the Post. He said his organisation had conducted a training for 800 teachers, including 200 principals, on corporal punishment a few years ago.

Sapkota, however, agrees that private school teachers have to work under more pressure than those in community or public schools.

“There are greater expectations from parents and pressure from the management,” said Sapkota. “This could result in violence. Such cases, however, are limited and cannot be generalised.”

Back in Barahathawa, after the recent incident, Sahani had refused to attend school, afraid that he would be punished again. It was only after the headmaster promised never to beat anyone again that Sahani’s parents convinced him to go back to school.

(Kashi Ram Dangi, Durga Lal KC and Chandan Kumar Mandal contributed to this report.)

10.17°C Kathmandu

10.17°C Kathmandu