National

Everything you need to know about the Nepal government’s new IT bill

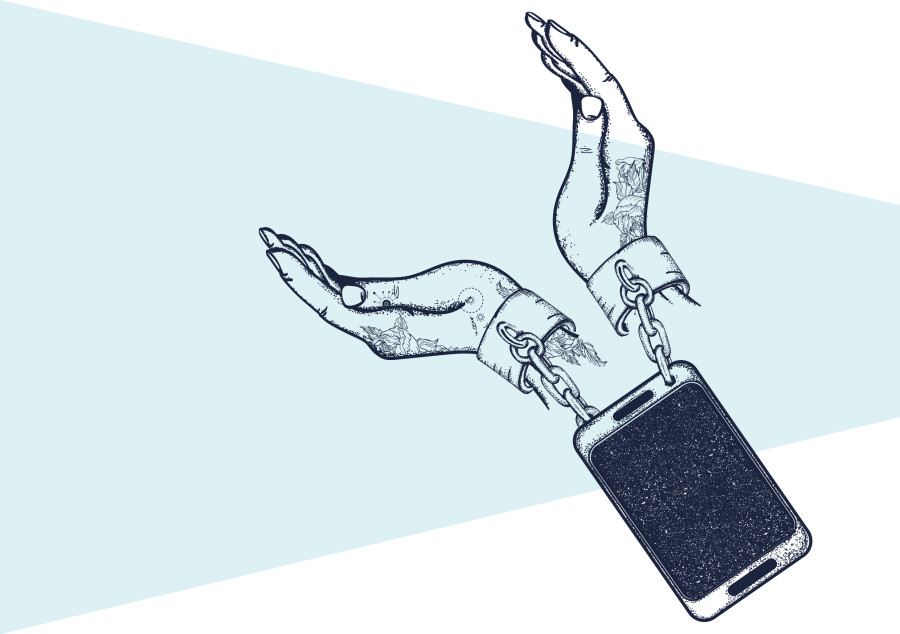

The controversial Information Technology management bill tabled at the parliament last week has raised several concerns about what this means for social media users and freedom of speech online.

Bhrikuti Rai

The controversial Information Technology management bill tabled at the parliament earlier this week has raised several concerns about what this means for social media users and freedom of speech online. But the comprehensive nature of the proposed bill which lumps together every cross-cutting sector that relates to information technology could push sweeping changes on everything from social media use to surveillance, e-commerce, and tech innovation.

Here is what you need to know.

What is the IT management bill?

The bill will replace the existing Electronic Transaction Act (ETA) and has been touted by the government as the most comprehensive and clear bill to address the long-held concerns around IT management. But the wide-scope nature and the vague language used in the provisions could give broad powers to authorities to block social media platforms if they are not registered in Nepal, threatening to curtail freedom of speech online as well as increase surveillance of personal data and also have more red tape for internet-based companies.

For example, the broad definition of “social network” in the bill includes all information and communication technology-based platforms where people and organisations interact or share content. This would include everything from Facebook, Twitter, Instagram to messaging services like Viber. Even the more secure platforms like WhatsApp and Wire could fall under the purview of the laws enacted through this bill.

The government has prescribed a fine up to Rs1.5 million and/or five years imprisonment for individuals who post online contents to sexually harass, bully or defame others.

[Read: Government's new IT bill draws battle lines against free speech]

How does it affect tech giants?

Nepal government wants internet companies like Facebook and Google to register in Nepal, set up an office in the country so they can be held accountable, and impose a tax for the money they make from Nepali users. But without a detailed plan in place from how taxations would work and the obstacles that exist for online payment gateway in the country, it is most likely that the government wouldn’t be able to implement everything it has set out to do to crack down on tech giants.

Industry experts agree that Nepal is too small a market for tech titans to go through a bureaucratic hassle to be allowed to operate here. Some of the companies have after all been banned in authoritarian regimes like China and North Korea.

Nepal also needs to first do its homework—from a business-friendly policy to necessary infrastructure to make the country a tech-hub—if it wants internet companies to come to Nepal and run as a registered entity, which IT entrepreneurs say would also benefit the country’s nascent but growing information technology sector.

[Read: New IT bill could kill innovation in Nepal, experts warn]

What does it mean for you as an individual?

The government has repeatedly said this bill will not stifle freedom of expression online and is only aimed at regulating tech companies. But the very nature of the bill, which is bent on criminalizing social media interactions—those could be deemed illegal based on the vague language of the provisions—puts the users at high risk of being penalized for online posts that “offend” politicians or bureaucrats.

The government has already been using the Electronic Transaction Act to arrest and take action against people based on their social media posts deemed “improper” by the authorities. According to the cyber crime cell at Nepal Police, 106 cases were filed in Kathmandu Valley in the last three years for posts on social media.

“Provisions in the new bill, which seeks to criminalise free speech by looking at it through the lens of decency and morality will dilute the protection enshrined by offline laws,” said Shubha Kayastha, co-founder of Body & Data which works in the intersection of gender, sexuality and digital technology in Nepal.

Why Internet Service Providers are worried, and why you should be, too.

The existing ETA’s definition of originator clarifies that intermediaries like the Internet Service Providers (ISPs) do not fall under the broad definition of “originator”, which includes anyone “who generates, stores or transmits electronic records, and this term also includes a person who causes any other person to carry out such functions.”

However, the proposed IT act removes the clause regarding intermediaries. This, IT experts say, could jeopardise ISPs who are merely the medium of the content created and shared online.

Given the stringent policies around content-filtering and the onus on internet service providers, there is a strong possibility that Nepali users will feel their choices being limited online or having to increasingly rely on VPNs. Internet service providers also don’t want the responsibility of actively filtering content with the fear of punishment over their heads. They are concerned about what these draconian rules would mean for internet users in Nepal.

“What kind of internet will the people get if we, the ISPs, start taking down sites one after another, to safeguard our business and because of the fear of government reprisal?” Binay Bohra, the managing director at Vianet Communications, an ISP company, told the Post in an interview earlier this week.

What will be the long term effects of the bill?

If the bill is passed in its current form, where government bodies from local, state to federal level, are given the authority to direct ISPs to take down content without the permission from the court, it could have dire consequences on everything from privacy to freedom of speech online.

The possibility of being confronted in a situation where multiple public bodies flood ISPs with requests to remove anything they deem illegal would overwhelm these companies in more ways than one.

Provisions in the draft’s current version provide plenty of room for interpretation that could give the government an upper hand on dictating whether or not certain types of equipment or software that a person or company uses could be deemed “illegal”. Experts have warned that such provisions could be used against particular individuals or institutions in situations when the government feels like it.

“If certain contents are deemed illegal, then it needs to be taken down with the permission of the court, it should go through a judicial process,” said advocate Babu Ram Aryal, who specializes in cyber law. “If it doesn’t, there might be a gross misuse of this provision.”

A ruling by the Supreme Court’s joint bench of the then Chief Justice Kalyan Shrestha and Justice Devendra Gopal Shrestha in February 2016 had instructed the government to have a mechanism in place to seek permission from concerned district court if they wanted to access phone calls and message records to investigate crimes. Experts say some of the provisions in the bill, which could give unchecked authority to multiple government bodies over people’s data, are trying to override the 2016 Supreme Court ruling.

What are the chances that the bill will actually work?

The comprehensive nature of the bill and its wide scope makes the implementation process challenging. The bill currently gives authority to multiple administrative bodies in the government to direct intermediaries to take down content they deem “illegal”. If the administrative bodies’ directions aren’t clear, then the people and bodies who have to follow those orders will have a hard time.

So how did we get here?

The KP Sharma Oli-led government completed a year in office this month. And it's been a particularly busy year so far for the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology. Last October, there was a major chest thumping by the ministry about the 20,000 plus websites it shut down for obscene and harmful content, which the ministry said was to curb sexual violence. The following month, Minister for Information and Communication Technology Gokul Prasad Baskota began “a new arrangement” of weekly updates on cabinet decisions, breaking the long tradition of media briefings that were held after every Cabinet meeting.

Three months later, more chastisement followed. On February 13, the ministry proposed a bill seeking to tighten the use of social media and regulate all internet-based companies in Nepal, just days after the government tabled a new law at the House of Representatives restricting civil servants from sharing their views on social networking sites. The bill, which was tabled in the Parliament last week, has provisions to fine or imprison individuals who post “improper” contents on social networking sites that the authorities deem as discrediting individuals and attack on national security.

Independent experts who have been working with the government for the past couple of years to amend the ETA say there has been intervention from Prime Minister’s Office as well as the Ministry of Home Affairs to include stringent policies on social media posts and give the information technology department the jurisdiction to order social networks to remove content.

Where else in the region has this kind of broad laws been put in place?

The past couple of years has seen an uptick in the laws and regulations to tighten online space worldwide. Democratically elected leaders in Asia have been on the forefront trying to silence dissent, put restrictions on the media, and crack down on individuals who share memes and posts that “offend” politicians. From the Philippines to Cambodia and India, people have been arrested and punished for expressing views online that didn’t sit well with their governments.

According to Freedom on the Net 2018 survey by the US think tank Freedom House, Asia had the most evidence of a negative trend of global internet freedom. India has more internet shutdowns than any other country in the world. Other Asian countries like Bangladesh, Cambodia, the Philippines, China, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Pakistan, Sri Lanka have seen a steady drop in the internet freedom index.

Coincidentally, the Oli administration has had several meetings with some of the leaders from these countries who have unleashed wrath on dissenting voices by cracking down on internet use, among others. In the past year, Prime Minister Oli and members of his government have met and interacted with the high-level officials from Cambodia, Myanmar and the Philippines among others, though it’s unclear if those meetings have inspired the growing restrictions Nepal’s government has attempted to put on freedom of speech and online freedom.

17.12°C Kathmandu

17.12°C Kathmandu