National

Nepal’s peace came with a promise for justice—but it’s been painfully slow

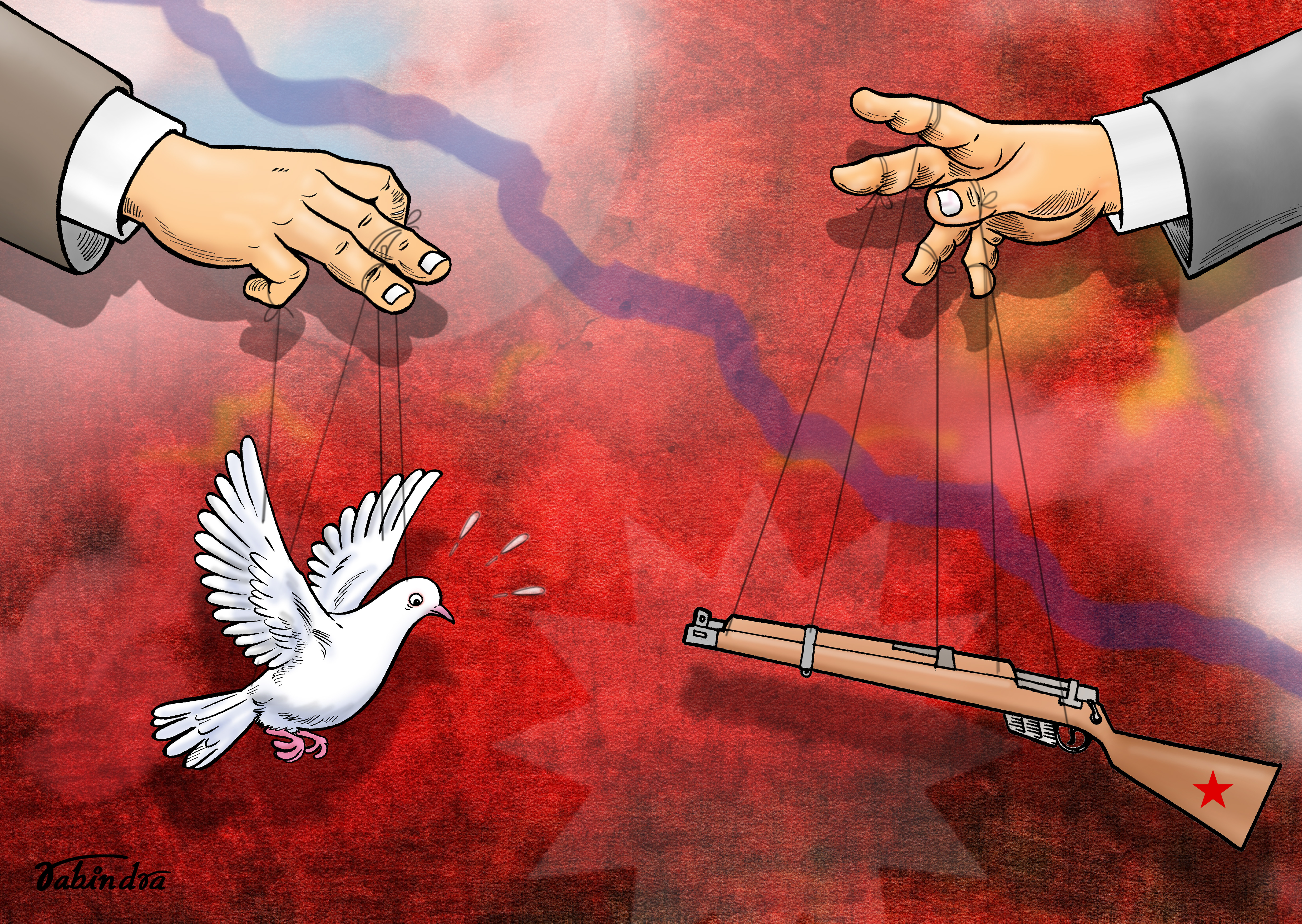

The imminent departure of the key people in charge of investigating and recommending punitive action for crimes committed during the 10-year-long insurgency that pitted Maoist rebels against the country’s security forces has not only thrown the timeline for completion of the transitional justice process into uncertainty but also raised serious doubts about whether the government, which the Maoists are a significant part of, and the political structure are committed to delivering justice to the conflict victims.

Binod Ghimire

In a quiet development last week, the government announced that it will bid farewell to the chiefs of two commissions that were formed to lead the transitional justice process. The imminent departure of the key people in charge of investigating and recommending punitive action for crimes committed during the 10-year-long insurgency that pitted Maoist rebels against the country’s security forces has not only thrown the timeline for completion of the transitional justice process into uncertainty but also raised serious doubts about whether the government, which the Maoists are a significant part of, and the political structure are committed to delivering justice to the conflict victims.

When the government and the Maoists signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2006 as a formal declaration of the end of the civil conflict, one of the major points was to ensure justice for all those who suffered at the hands of the state and the rebels.

In order to provide restorative justice, the agreement envisioned the formation of a high-level Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). It was tasked with bringing to light serious violations of human rights and crimes against humanity and creating an environment that would facilitate reconciliation.

But political brinkmanship and continued squabbling among the various political parties and the security forces, especially the Nepal Army, have meant that it took nine long years to even form the two transitional justice commissions--TRC and the Commission of Investigation on Enforced Disappeared Persons--in 2015. Even then, they remained largely dysfunctional for more than a year, until regulations for them were endorsed by the Cabinet in 2016. By then, a year of their two-year mandate had already been lost. A month later, the commissions finally began collecting complaints from conflict-era victims.

But the obstacles didn’t end there.

The law enacted in 2014 to deal with war-era cases--Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act 2014--had little consolation for victims; instead, it paved the way for the exoneration of political leaders and security personnel who were active during the insurgency. For instance, the Act did not specify cases of serious human rights violations. All cases, including serious ones like rape, torture and enforced disappearance and relatively minor ones like arson, were placed in the same basket, leading to fears that general amnesty might be applied even to serious cases of human rights violations. In 2015, the Supreme Court took issue with the law and ordered that amnesty provisions for those guilty of serious human rights violations be removed. Successive governments, however, failed to amend the law.

(Right) Girija Prasad Koirala, on behalf of the government, and Maoist commander Pushpa Kamal Dahal, sign the Comprehensive Peace Agreement on November 21, 2006. [Post File Photo]

(Right) Girija Prasad Koirala, on behalf of the government, and Maoist commander Pushpa Kamal Dahal, sign the Comprehensive Peace Agreement on November 21, 2006. [Post File Photo]Despite this failure to honour the Supreme Court’s directives, around 63,000 complaints have been filed with the truth commission and around 3,000 with the disappeared commission. Conflict victims, however, have never really been convinced that they will receive justice, given the workload of the two commissions and their lack of resources and laws.

“We knew that commissions formed out of pressure would never deliver justice, which has been justified after four years,” said Phanindra Luitel, general secretary of Conflict Victims National Network, one of the two umbrella bodies of conflict victims.

Now, four years since the commissions were constituted, their terms have been extended by another year. This time, the two commissions will bid farewell to existing officials in April and new officials will take over in an attempt to ensure some semblance of a ‘revamp’ to the transitional justice bodies--something conflict victims have long been demanding.

But given the previous approach of the transitional justice mechanism--and the unwillingness of the political leadership--the recent term extension has done little to boost victims' hopes.

"This term extension barely scratches the surface," Man Kumari Ranjitkar from Kavrepalanchowk told the Post. Man Kumari’s husband, Rajbhai, was abducted by security forces in 2005. He never returned. She has spent the last 14 years trying to find her husband’s whereabouts.

When the disappeared commission called for applications in June 2016, Man Kumari had filed a complaint.

“I don't know whether I will ever know what exactly happened to my husband,” said Man Kumari. "The commission where I had filed the complaint has failed to take any concrete step towards revealing the status of my husband."

The two commissions were formed on February 9, 2015. The month of February holds great significance for the Maoists, who mark a day in mid-February every year as a day to pay tributes "to all those who sacrificed their lives" for the ‘people’s war’ and the cause of socio-political transformation. It was on February 13, 1996 that the then Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) officially launched its ‘people’s war’, attacking a number of targets across the country.

Combatants from the Maoist People’s Liberation Army conduct a training drill. [Post Photo: Kiran Panday]

Combatants from the Maoist People’s Liberation Army conduct a training drill. [Post Photo: Kiran Panday]But for the last four years, the month of February has been a time when old wounds are torn open for conflict victims. On February 13 this year, as the former Maoists celebrated their rebellion against the state, Purni Maya Lama recalled the day they abducted her husband Arjun Bahadur Lama, on April 29, 2005. Arjun was subsequently killed.

Arjun Lama’s murder case is currently sub judice at the constitutional bench of the Supreme Court. Purni Maya, who is originally from Dapcha, Kavre but currently lives in Kathmandu, has also filed a petition with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“It’s more than a decade since I started my legal fight to bring the perpetrators to justice,” Purni Maya told the Post. “I went to the courts first. Then, I approached the transitional justice commission. They have both failed me.”

***

Two years after the peace deal, the Maoist party swept the 2008 Constituent Assembly elections. Pushpa Kamal Dahal became prime minister. Conflict victims hoped that with the once-rebel Maoists in power, justice was on its way.

Although piecemeal approaches were made at filing cases against perpetrators of human rights violations, transitional justice was only really possible through the due process, i.e., investigation by a credible truth and reconciliation commission. But parties on both sides of the conflict kept dragging their feet.

In October 2017, more than a decade after the formal end to the conflict, the Maoists decided to join with the CPN-UML—two parties that were once on opposite sides of a civil conflict now came together to form the largest political party in the country. Once again, they swept the elections in December. With the unified Nepal Communist Party now at the helm of government, there was also a notion that the top leaders of the party—Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli and Pushpa Kamal Dahal—were on the same page on how to take the transitional justice process forward.

But officials from the two commissions said that support from the current government was largely lacking. Lila Udasi Khanal, a member of the truth commission who resigned on February 8, told the Post that the government had worked to weaken the commissions, rather than strengthening them.

"It is clear from our experience that the two transitional justice bodies were formed out of compulsion. The governments never intended to let them function," Khanal said. “It's not about one particular government; none of the governments in the past was committed to transitional justice. There were numerous constraints. We were hamstrung by a lack of laws and resources."

More than a decade of sluggish development has also tired out conflict victims and made them wary. They have long been saying that the commissions were not capable of delivering justice and had demanded a complete ‘restructuring’ of these two transitional justice bodies.

Conflict victims' groups and civil society members complain that former commission officials were more focussed on legalities, rather than ensuring justice. They hope that the installation of new officials in April will reinvigorate justice delivery, they said.

“Had they been sincere, nothing would have stopped them from finding the truth. A lack of [legal] amendment would not have stopped them from investigating cases that had been filed to them,” said Suman Adhikari, former chair of the Conflict Victims Common Platform, who is now with another conflict victims' group called Conflict Victims National Network. “The officials had been pointing fingers at the government only to hide their incompetence. Four years were squandered."

But commission officials disagree.

“Yes, a lot more could have been done, but what we have achieved so far also cannot be ignored," Lokendra Mallick, chairman of the disappearance commission, told the Post. "It’s wrong to conclude that we wasted four years. We have set the foundation, easing the job of our successors.”

Sher Bahadur Tamang, former minister for law and justice under whose leadership a ‘zero draft’ to revise the existing Transitional Justice Act in line with the Supreme Court directives and international obligations was prepared, agreed that it would be wrong to blame just the commissions for their failure to deliver.

“The legal ground under which these commissions were formed was weak, which reflected in their performance," said Tamang. “The commissions did not have enough authority to investigate and the appointment process for the officials was flawed.”

***

The primary concern of conflict victims is that the transitional justice process has not been victim-centric. Without the representation of victims in truth and reconciliation, the process will remain incomplete, they say.

Both victims’ groups—Conflict Victims Common Platform and Conflict Victims National Network—want their say in the law amendment process as well as the appointment of new leadership to the commissions.

Of late, a consensus too seems to have built among the political parties to take the transitional justice process to its logical conclusion by incorporating victims into the entire process.

Sources familiar with developments and ongoing negotiations told the Post that Prime Minister and Nepal Communist Party (NCP) Co-chair KP Sharma Oli, Co-chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal and Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba have all agreed to ensure victims' representation in commissions, fix reparation schemes and amend the Act. The penalties for perpetrators will also be decided on after holding consultations with victims, the sources said.

“The cross-party leadership is now convinced that the longer we take, the more complex the process will become," a senior legal expert familiar with ongoing negotiations told the Post on condition of anonymity.

Continued delays and the past approaches of the commissions have also drawn the attention of the international community, which has refused to assist the government largely because of its failure to amend the laws in line with the court’s verdict and international obligations.

Combatants from the Maoist People’s Liberation Army conduct a training drill. [Post Photo: Kiran Panday]

Combatants from the Maoist People’s Liberation Army conduct a training drill. [Post Photo: Kiran Panday]In January, nine Kathmandu-based diplomatic missions, at the initiative of the United Nations, urged the government to publicly clarify how it plans to take the transitional justice process forward.

Last week, on February 11, Amnesty International, the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) and TRIAL International jointly warned that the recent term extension should not become another missed opportunity to ensure that victims are provided with the justice, truth and reparations they so desperately seek. A further one-year extension will be meaningless if measures are not taken to secure the independence and impartiality of the commissions, they said.

“This can only be achieved through a transparent selection process driven by a genuine will to combat impunity—not just for conflict victims, but for future generations,” said Frederick Rawski, director for ICJ Asia Pacific.

For the international community, the one vital area where the government needs to make amends concerns punitive action for perpetrators, said the legal expert, who is supporting the government in drafting the amendment bill.

The international community does not seem to be happy with the severity of punishment the political leadership is considering for those guilty of serious human rights violations.

“Community service type punishment won't work. There has to be prosecution and punishment in a true sense, even if it's symbolic. This is what the international community thinks,” he told the Post.

The completion of Nepal’s transitional justice process will require the fulfillment of four components—truth finding, prosecution, reparations and a commitment to ensure that such incidents do not repeat in the future.

But the drawn-out process has exhausted victims, with many of them saying reparation was their immediate need. After interacting with conflict victims from 73 districts, Lila Udasi Khanal, the truth commission member who resigned on February 8, affirmed their first priority has always been reparations, contrary to what a large section of human rights defenders claim in the Capital. Victims want the government to take care of the education of their children, ensure employment for at least one member of the family, in addition to an official acknowledgement from the state and concerned parties, he said. Shree Krishna Subedi, another member of the commission, said in a public programme last month that 90 percent of the victims prioritise reparation, while just 10 percent are focussed on prosecution.

Purni Maya, whose husband was abducted by the Maoists, said that the state has altogether forgotten her and victims like her. "Apart from the Rs1 million in compensation, I have received nothing from the state. We have become an object of neglect,” she said.

***

Nepal's quest for transitional justice has been a politically-charged affair from the very beginning. All 10 members—five each in the two commissions—were picked on shared political quotas. The majority of them were installed in the commissions given their affiliations with the political parties, rather than their qualifications. This led to the commissions being seen by victims and civil society as political tools and thus, did not receive cooperation. An official at the truth commission said that victims’ groups had refused to even come to the commission’s office. The commission had to hold meetings at a hotel.

A member of the commission, who did not wish to be named as he was not authorised to speak to the media, agreed that ‘political appointments’ might have been one reason that the victims and civil society refused to cooperate with the commissions.

“We might have been selected for our political proximity, but it would’ve been very insincere to act as a party cadre after getting the appointment. Some of our friends did forget their core responsibility,” the member said.

Some officials at the truth commission also blamed the lack of an assertive leadership for the poor show. And there were disagreements among officials.

Surya Kiran Gurung, who resigned as chairman of the truth commission on February 8, two days after the terms of the two commissions were extended, was caught in a dispute between two members who were appointed under the Nepali Congress and the then CPN (Maoist Centre) quota. For over two years, Gurung was not even on talking terms with one of the commission members.

Gurung had attempted to resign once before, in 2017, but had withdrawn his resignation after cross-party leaders, including then prime minister Sher Bahadur Deuba, assured him that they would create an environment conducive for him to work. That, however, never happened. Gurung later said that he had resigned because that it had become impossible for him to tolerate the “irresponsible acts” of some of his members.

***

When the Supreme Court in February 2015 struck down amnesty provisions in the Enforced Disappearances Enquiry, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act, it also said that around a dozen other provisions were inconsistent with international norms and practices. The court also sought clarity on provisions related to ‘serious crimes’, ‘serious human rights violations’ and ‘other crimes of a serious nature’.

Last week's was the second amendment to the Act, but it was for the extension of terms of the two commissions. This amendment also fell short of meeting the Supreme Court directives and international obligations. It appears that the political parties remain reluctant to amend the laws. Contesting voices from victims' groups and human rights defenders, as well as pressure from the security agencies, particularly the Nepal Army, are equally responsible for this reluctance, said officials from both commissions.

“Everybody should understand that the world is watching us and we can’t delay the process for indefinitely,” a senior government official, who did not wish to be named as he was not authorised to speak to the media, told the Post. Any further delay could prompt the international community to build more pressure, he said. “The international community, or the United Nations for that matter, might want to step in to complete the remaining tasks of the peace process. The process must be completed in a maximum of two years as prescribed by law if we want to resolve it on our own.”

Meanwhile, victims like Purni Maya said their hopes were fading. "I don't know who I should trust. I don't think anyone in this country is genuinely interested in ensuring justice and reparations for victims like me," she said.

As Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali prepares to travel to Geneva later this month to participate in a meeting of the UN Human Rights Council, of which Nepal is a member, he is certain to face tough questions from the international community.

Gyawali told the Post on Tuesday, February 12, that he would defend Nepal’s transitional justice process in Geneva. “I will tell the international community that there will be no blanket amnesty for perpetrators of serious human rights violations,” he said. “War-era cases of gross human rights violations will be dealt with by the courts while the entire investigation process will be victim-centric. I will inform the world that the Nepal government will respect—and adhere to—the Supreme Court’s verdict.”

But for victims, Gyawali’s promises still ring hollow. What matters, said Suman Adhikari, is truth and justice: “We just want to know what happened to our relatives. Why were they killed or abducted and who did it?”

17.9°C Kathmandu

17.9°C Kathmandu