National

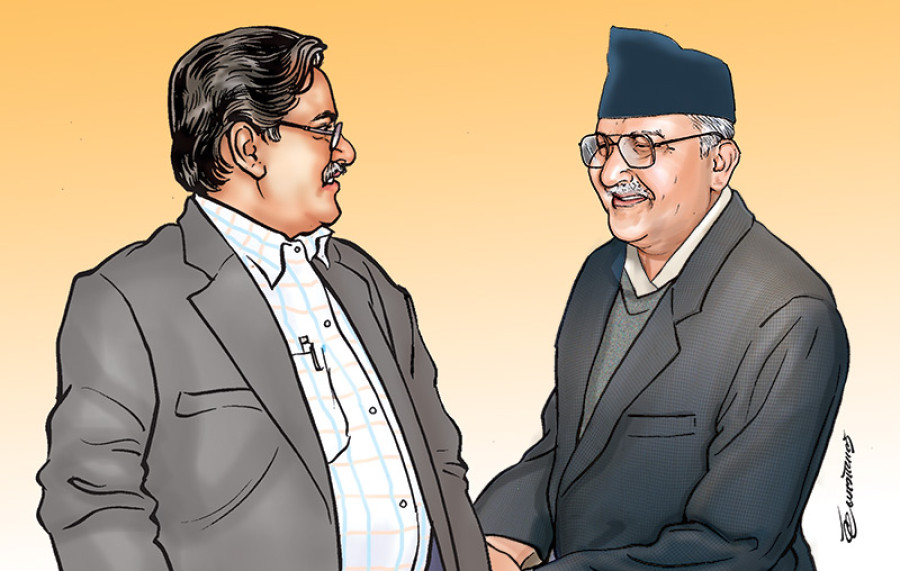

Oli and Dahal form a formidable team

The unification process between the CPN-UML and the CPN (Maoist Centre) is one of the most significant events in Nepal’s recent political history, and certainly the most significant one since the peace process started in 2006.

Akhilesh Upadhyay

The unification process between the CPN-UML and the CPN (Maoist Centre) is one of the most significant events in Nepal’s recent political history, and certainly the most significant one since the peace process started in 2006.

The unification will firmly put the left alliance in the driving seat in Nepal’s politics at least for the next five years, and perhaps well beyond. And the two major proponents of the unification process—UML leader KP Oli and Maoist supremo Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’—will be at the centre-stage of Nepal’s politics for that period and are set to leave behind strong footprints.

Starting with the first phase of local elections that took place last May, through the next two phases over the next few months, and finally the provincial and federal parliamentary elections in two phases late last year, the UML established its electoral dominance. The dominance was near-absolute in the provincial and federal polls after the two parties came together as the left alliance and shared tickets—on a 60: 40 ratio, with the larger of the two parties, UML, getting a greater share.

The Oli government now enjoys close to two-thirds majority, and if Upendra Yadav’s Sanghiya Samajbadi Forum-Nepal (SSF-N), with 16 seats in the House of Representatives, joins the coalition, it will have the support of more than two-thirds of the House. No party has held a majority since the peace process started in 2006 and only on two previous occasions, in 1991 and 1999, did Nepal have a majority government in office. The Nepali Congress-majority governments, however, collapsed without completing their tenure due to infighting.

“The current unification will establish KP Oli and Prachanda as the most influential leaders in national politics, leaving other party leaders far, far behind,” says Shyam Shrestha, a left-leaning thinker and former editor of Mulyankan magazine. The duo will share the party chair until the left alliance holds its national convention to elect a new leadership.

The big question now: Will the ongoing unification process see the UML and Maoists come together as a single party—they after all have vastly different ideological and political bases? By all accounts, the unification will hold, primarily because Oli and Prachanda need each other for their own political survival and they complement each other very well, say analysts.

Their mutual dependence was best witnessed last week when Oli took office and Prachanda refused to participate in the government until the outstanding unification issues were settled first.

Oli has proved to be a master strategist—he could sell the idea of 60:40 deal within his party, at a time when the Maoists’ electoral strength was fast on the wane and the UML had established itself as the number one party in all three phases of local elections.

But Oli obviously saw that aligning with the Maoists, despite their electoral shortcomings, had political value long term—something the Nepali Congress President and then-Prime Minister Deuba failed to do.

“Without the Maoists’ support the left government will not be able to last a full term,” says Shrestha, “even if they plan to somehow find allies to garner a majority.”

Politically speaking, Prachanda brings to Oli a broad swathe of constituencies—the Madhesi, Janajati, Dalits, the marginalized groups that have traditionally been the Maoist base. The Madhes-based parties once considered boycotting the local elections because their repeated attempts to amend the constitution had failed due to UML intransigence. But Prachanda always got the benefit of the doubt from the Madhesi parties.

When Prachanda was the prime minister in 2016-017, almost all the Madhesi leaders interviewed said, he was ‘positive’ on amending the constitution, that he was ‘flexible’ and he was “constrained by the UML position”.

As prime minister, Prachanda repeatedly assured the Madhesi leaders in public that he wouldn’t fix the date of local elections without their consent and that constitutional amendment was as important for him as it was to them.

“Prachanda is viewed positively by the Madhesi leaders and voters,” says Dipendra Jha, a Madhesi lawyer who has just been appointed chief attorney in Province 2. “I expect that his presence in the left alliance will have a positive impact on Oli who is not viewed favourably by Madhesi parties.”

Prachanda also has another important constituency—the international community, which has worked closely with the Maoists since the peace process started in 2006, though his inconsistency has irked many allies. While the United States stayed away from the Maoists in the early stage of the peace process, the United Nations, the UK, Switzerland and European Union arguably contributed strongly to the political mainstreaming of the Maoists. Many senior Maoist leaders now enjoy personal rapport with senior diplomats and officials from the Western countries and the United Nations, thanks to their long association.

“We don’t see the Maoists as hostile communists,” says a senior diplomat based in Kathmandu. “We have done business with them for a long time.” Still, Oli is seen as a far more consistent leader than Prachanda, including by New Delhi. Oli also enjoys very good relationship with Beijing, his credentials strongly buttressed after he signed 10 framework agreements with China to diversify Nepal's trade and transit during his last stint as prime minister.

Though Oli and Prachanda’s politics seem to be converging, it is Oli who sits firmly on the nationalist plank. Since India’s undeclared border blockade in 2015-16, Oli’s stature has steadily grown in Nepali public perception, a rise that was further cemented with the left alliance’s landslide in the provincial and federal parliamentary elections. The fact that he could sell the 60:40 deal within his party showed Oli has far greater political acumen and power of persuasion than his political cohorts within his party and outside.

Also, the left alliance helped project UML’s political superiority as a ‘senior’ communist party. But to many, Maoist Chairman Prachanda has been an unsung hero. The fact that he could sell the idea of a combined larger left outfit to Oli, at a time when his own party’s strength had been on a steady decline after its hey days in 2008, shows that Prachanda can constantly reinvent his politics.

“The unification once again brings Prachanda back to the political centre-stage,” says analyst Shrestha. The move rescues his personal politics, his party and it, in all probablity, puts Nepal on a track to political stability and, in extension, to prosperity.

The unification process demonstrates the political acumen of two of Nepal’s shrewdest political players. Oli has come far because of his steadfast political belief, someone willing to confront the opposition hard; Prachanda, on the other hand, as a flexible dealmaker.

“In any important negotiations, Prachanda goes in with more than two well thought-out positions and he puts in his position after a careful observation. He is quick to seize the opportunity,” says Shrestha. “He is a deal maker.” Even when his party was the third largest in Parliament, Prachanda continued to be at the centre-stage of national politics.

“Oli meanwhile sticks to his position–to the extent that he tires out his opposition and develops an entirely new constituency,” says Shrestha. “Minority constituencies haven’t always viewed him favourably. But Oli is backed by a sizeable party machine and patronage networks.”

Now that they have come together, the two form a formidable political team which is all set to dominate Nepal’s political landscape for a long time to come. For now, Oli’s obduracy and Prachanda’s flexibility has worked well for them both, their parties and Nepal’s politics moving towards stability.

11.42°C Kathmandu

11.42°C Kathmandu