Movies

The bittersweet art of letting go

‘Happy Old Year’ explores memory, loss, and the struggles of moving on.

Sanskriti Pokharel

Memories reside not only in our hearts and minds but also in the things around us. The withered flower bouquet in the corner of your room might hold the memory of a beloved and their love. The empty pickle jar on your cupboard could carry the memory of your mother lovingly making pickles to ease your homesickness. A piece of cloth you borrowed—or perhaps stole—from your sibling might be a keepsake of bittersweet childhood quarrels.

Every tangible and intangible thing carries memories. Even if some items seem useless, we struggle to let them go because of the emotions and attachments tied to them. These objects become a part of who we are, and letting them go can feel like losing a piece of ourselves we cherish deeply. Even when we want to declutter our space, the things we’ve collected over the years often feel too precious to discard.

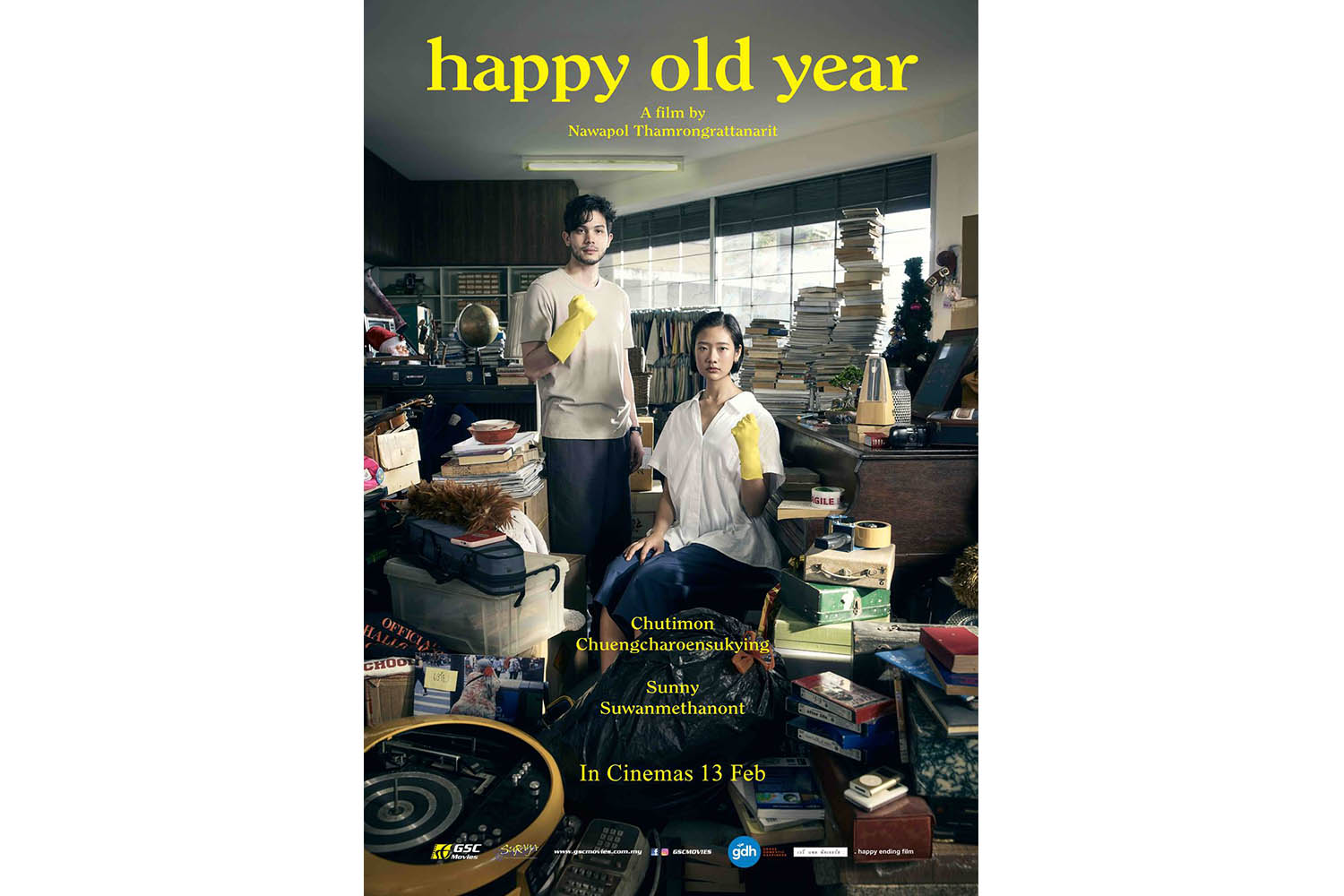

This is what the movie ‘Happy Old Year’ is all about—decluttering your home and your life by letting go of things. Directed by Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit, it is a poignant exploration of memory, loss, and the difficulties surrounding moving on.

The film opens with an exposition set in stark, white, empty rooms that exude a minimalist vibe. The protagonist, Jean (Chutimon Chuengcharoensukying), is seen giving an interview in this expansive, pristine space. She appears relaxed, her face lit up with a cheerful smile. However, the smile quickly fades, and the screen transitions into the opening credits. Only upon a second viewing might one realise the exposition subtly reveals the movie's ending, cleverly hidden in plain sight.

After the opening credits, the movie unfolds chronologically. Jean, portrayed as an ambitious young woman, begins transforming her family home into a minimalist workspace. Once an abandoned music school, the house is crammed with overwhelming clutter.

When Jean convinces her mother to throw away things, she refutes. Her refutation signifies cultural context and also adds richness to the narrative. In many Asian societies, objects and traditions are imbued with collective memory and familial bonds. Jean’s minimalism is inspired by Western philosophy and clashes with her mother’s traditional beliefs.

However, Jean approaches the process with the cool efficiency of someone who has embraced Marie Kondo’s philosophy of only keeping what ‘sparks joy’. Yet, as she sorts through the objects in her home, the past resurfaces in ways she hadn’t anticipated.

One of the pivotal moments arises when Jean discovers items belonging to her ex-boyfriend Aim (Sunny Suwanmethanont). What begins as a pragmatic decision to return his belongings spirals into a confrontation with her unresolved guilt and regret over their failed relationship. Each item, no matter how mundane, becomes a vessel of memories. It forces Jean and the audience to grapple with the emotional hurdle of letting go.

On a surface level, ‘Happy Old Year’ critiques the minimalist ideal by exposing its emotional and cultural blind spots. Decluttering is not just about objects; it’s about people, memories, and the stories we tell ourselves. Jean’s initial coldness, her insistence on discarding and throwing anything that doesn’t fit her vision of the future, is challenged by the messiness of human relationships.

As I watched, I couldn’t help but reflect on my own attachment to certain objects. When I moved to Kathmandu after SEE, I realised that if I had brought all the items dear to me, they would have never fit into my hostel room. Letting go of so many things was emotionally challenging, yet it was something I had to do.

A dog-eared book gifted by a childhood friend, an old scarf with frayed edges—these items are far from functional, yet they hold a weight that’s hard to quantify. The film masterfully captures this emotion and reminds us that while physical objects may take up space, they also anchor us to who we are and where we’ve been.

The protagonist, Jean, is not an easy character to like. Her cold pragmatism, especially in the early scenes, makes her seem selfish and detached. Yet, as the narrative unfolds, her vulnerability begins to seep through. Her vulnerabilities humanise her so well, portraying her as someone we can relate to.

The ending is deliberately ambiguous. For some, this lack of resolution may be frustrating. But for me, it felt honest. Life doesn’t offer tidy conclusions, especially regarding relationships and self-reconciliation. This lack of closure is not a failure of the narrative. It felt like an intentional choice by Thamrongrattanarit to reflect the reality that emotional healing is often non-linear and incomplete.

As someone who cherishes the sentimental value of objects, ‘Happy Old Year’ hit me like a quiet storm—unexpectedly powerful, deeply personal, and emotionally resonant.

However, this is not for everyone. Its slow pacing and introspective tone require patience and emotional investment, which might bore some viewers. But this film offers a deeply moving cinematic experience for those willing to engage with its themes.

If I were to summarise the film in one word, it would be ‘cathartic’. Not in the explosive, tear-filled way of a Hollywood drama, but in the quiet and sombre realisation that sometimes, the hardest thing to let go of is not the object itself but the version of yourself it represents.

Happy Old Year

Director: Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit

Cast: Chutimon Chuengcharoensukying, Sunny Suwanmethanont, Apasiri Nitibhon

Duration: 113 minutes

Year: 2019

Language: Thai

16.16°C Kathmandu

16.16°C Kathmandu