Movies

Can Nepali cinema survive the viral outbreak?

The Post’s in-house film critic on what the ongoing pandemic could mean for the Nepali film industry which is already fraught with problems.

Abhimanyu Dixit

It feels like forever, but the last film I saw in a theatre was only two months ago. I was in Kolkata travelling without a shadow of worry. It was my last day in the city, and I decided to experience IMAX before heading back to Kathmandu.

The film I was watching was ‘1917’, which was being touted as Sam Mendes’ technological marvel. I expected the theatre to be filled with people, as Kolkata is known for its vibrant cinema culture. But there were only three people in the theatre, including me.

Things seemed off. Then, during the interval, I overheard the popcorn vendors discussing there were 40 confirmed Covid-19 infections in Southern India, some 2,000 kms away. It was then that I looked into my bag of popcorn—a little fearful for the first time—and gave it a second thought. It would take me another month or so to truly understand the gravity of the crisis that was unfolding, especially for the Nepali cinema.

Today, we’re on the seventh week of the lockdown and it looks like it’s not going to end anytime soon. With their shooting schedules postponed, Nepali celebrities have found news ways of entertaining themselves and their audiences. Reema Biswakarma holds regular interaction sessions with her fans where she’s discussing everything from Covid-19 to films to food. Others like Keki Adhikari and Priyanka Karki are also regularly interacting with fans on social media. And although social media seems to provide some relief, the larger truth is that the industry has come to a grinding halt. And its future is uncertain. Even scarier is the fact that many insiders doubt that the industry will get back on its feet even after the lockdown opens—whenever that is.

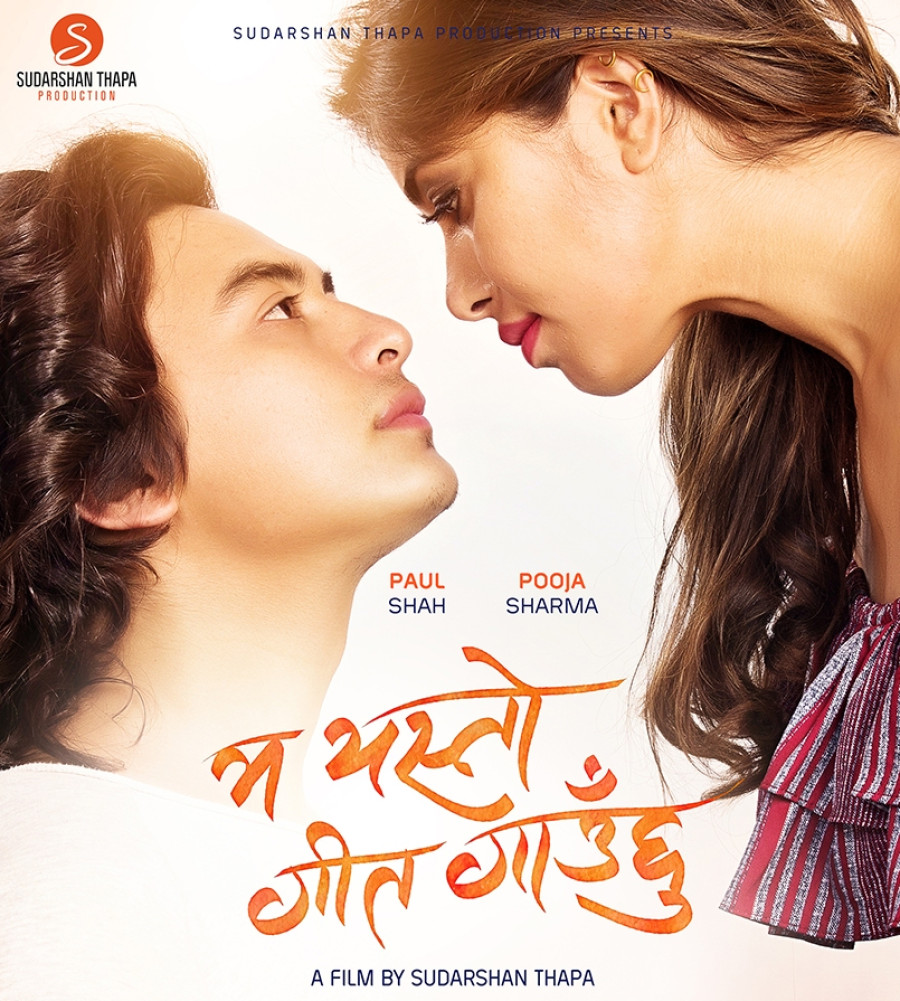

Santosh Sen’s ‘Prem Geet 3’, Sudarshan Thapa’s ‘Ma Yesto Geet Gauchu 2’, and Arjun Kumar’s ‘Chapali Height 3’ were all ready for release and were in the midst of promotions when the lockdown was announced. And even after the lockdown eases, these filmmakers will hold back their release dates because, well, they’re all franchise films with large investments, and do not want to take chances. The CEO of QFX cinemas, Roshan Adiga, in an interview with Kantipur, said they’re set to close until June, which means Nepali films will be stuck in limbo at least until the mid of this year.

But even before the lockdown began in Kathmandu, things had begun to be wary. As people knew very little about the virus, shooting schedules were disrupted and filmmakers were pushing their release dates. There were confusions about payments, contracts, and pre-selling of overseas rights. And then before anybody could understand anything, the lockdown was announced. Things were brought to an abrupt pause, and we couldn’t do anything but stay home.

But what we also need to consider is that Nepali films weren’t doing well even before the virus. Last year alone, only three out of around 55 films were financially successful and only seven broke even. Covid-19 is only another addition to a long list of problems Nepali cinema was already struggling with. Filmmakers have always battled against adversities since the inception of cinema in Nepal.

The first Nepali film was produced from Kolkata in 1951. Nepal’s first film came much later from Kathmandu in 1964. And we fell in love with it right away. In 30 quick years, we already had our superstars, chartbusters, and multiple film halls around the country. In the '90s there were around 500 cinema theaters, including Hi-vision halls and video halls. That is without counting many unregistered screening spots that showed films through a VCR.

But with the armed political conflict and persistent attacks on theatre owners during the insurgency, hundreds of theatres closed down. Quantity and even quality of Nepali films produced during this time suffered. Director Dipendra Lama, who worked as a film critic then, says, “A lot of films were just ripping off Indian cinema at that time.” The storyline, characters, action sequences, and even the sound design and background scores in the films of that time bear striking resemblance to Hindi films.

Lama and his contemporary reviewers, including directors like Deepak Rauniyar and Manoj Pandit, were doing their best to discourage the practice through their writing. “Reviewers from my generation always pointed out the copy-paste trend, the unoriginality, dependence on technology, and shunned music-video style filmmaking,” Lama adds.

Then, when the digital age rolled out, it helped evolve the Nepali cinema. It provided a platform for original stories from young filmmakers. It became easier to create, distribute, and exhibit cinema. Cheaper DSLR cameras and home-assembled editing suits encouraged a new batch of filmmakers.

This new wave gave us directors like Nischal Basnet, Rambabu Gurung, Prashant Rasaily, and Deepak Rauniyar, all of whom had a distinct style of presentation and storytelling. Abinash Bikram Shah, a screenwriter who has worked closely with many of these filmmakers, says, “Technology and access to world cinema made it easier for young Nepali makers to express themselves through cinema. This in-turn gave us recognition in the international festival scene.”

Along with the filmmakers, Nepali audiences too were also rediscovering Nepali cinema, and films ran to packed theatres. Then, came the 2015 earthquakes that put the industry at a standstill for almost four months. The films that were released after the standstill had better storytelling and were commercially successful.

Makers like Dipendra K Khanal, Deepak Raj Giri with Deepa Shree Niraula, and Khagendra Lamicchane told local stories in their genre of comfort. Nepali filmmakers enjoyed international exposure in notable festivals too. Feature-length films of Min Bham and Deepak Rauniyar, and short films from Pooja Gurung with Bibhusan Basnet, Rajan Khatet, and Ankit Poudel garnered accolades around the world. Major film labs and notable international festivals began noticing Nepali films and investing in our stories.

Filmmaker Prashant Rasaily, who is watching Kathmandu closely from Gangtok, has a rather optimistic outlook on the current scenario—despite the gloomy reality. “Every-time there is a huge world-changing event—a variety of significant contents have emerged. The Second World War gave us Italian Neo-Realism and French New Wave Cinemas,” he says. These waves transformed cinema across the globe, and he hopes for something similar now.

Deepak Rauniyar believes online screening and virtual cinema might be the new norm. He is optimistic of newer technology coming into the forefront. His film ‘White Sun’ is available on Amazon prime, and he hopes for other Nepali films to follow suit. “There’s a lot of online streaming platforms coming up in South Asia, and they’re interested in Nepali cinema for their catalog,” says Rauniyar.

Nepal too has its own streaming services that seem to be doing well for themselves, like iflix, Video Pasal, and Dish Home. More such streaming services are slated for launch in the near future. “After the pandemic, traditional establishments like cinema halls might collapse entirely, and online platforms might not be enough for filmmakers to survive on,” says Rauniyar.

However, for the industry to survive, private investments will not be enough to make the industry stable. Therefore the need for the hour is government intervention. Rauniyar says that in New York, the government has “announced stimulus packages for small and larger companies working in cinema.” He says that these desperate times call for viable mechanisms to help sustain the cinema industry. Some Nepali filmmakers, distributors, and exhibitors from the Nepal Motion Pictures Association agree with Rauniyar. To bring that into effect, they submitted a memorandum to the Finance Minister Yubaraj Khatiwada recently. The memorandum broadly requests for a care package to save Nepali cinema from economic devastation.

But the Nepali government has notoriously stayed away from any sort of investment in Nepali cinema. The closest the government has come to working with the industry was when Visit Nepal 2020 had a programme that promoted ‘Nepal as a film destination’. While the programme might have helped Nepal appear on the global map as a tourist spot, there’s nothing for the local cinema industry.

The next most viable alternative for cinema then is international funding but that too will require government assistance. International funding and co-production opportunities with filmmakers from foreign countries require the state to be involved at the policy level. A co-production agreement usually requires both countries agreeing on certain prerequisites. “Filmmakers today need the state’s support, participation, and investment," Rauniyar says.

We also need government organisations like the Film Development Board to learn from international examples. The countries that boast of a strong film culture—Korea, India, Iran, and lately the Philippines—all enjoy a very strong support from their respective governments. For example, in India, the National Film Development Corporation organises film markets and supports independent films.

For now, no one really knows how this pandemic will turn out. But it’s in our best interest if we can plan ahead our route to normalcy. Although there are many other areas that require urgent attention, cinema and art will be important in helping us ease into normalcy. Cinema until now has survived two global wars, numerous political transitions, and economic devastations. Nepali cinema can even add natural calamities to that list. But positivity and perseverance has carried us through tough times. Hopefully, it will now too.

See you at the cinemas, soon.

21.11°C Kathmandu

21.11°C Kathmandu