Money

Book imports at a trickle as issues remain unresolved

Government not backing down on decision to tax books published in West based on their original value even as importers pay discounted Indian prices.

Post Report

In July, a book on United States President Donald Trump was published. Since he was elected president in 2016, hardly a week goes by without some scandal involving the former businessman and reality star. He seems to be an intriguing character, and because he is so different from past US presidents, there is an insatiable public demand for writings about his shenanigans. To fulfil this market demand, a number of show-and-tell books on him catch the public imagination and sell well. But this latest book was different.

His niece wrote it. Mary Trump is a trained clinical psychologist, and she looks not at his misdeeds since he came to office or his earlier business dealings as other books have done, but delves into the mind of Trump. It is a study on how he was formed by his relationship within the family, particularly with his father, and how the two treated the author's father, Trump’s elder brother. Trump and his lawyers failed to prevent the publication of the book. By the end of the first day of its release, it had sold almost a million copies.

Newspapers in different Western countries have written extensively about the book. Sadly, Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World's Most Dangerous Man is not available in Kathmandu. It is not because there is no demand for the book and distributors are not interested in marketing it that it is not being imported. It is because of the government's policy on taxing imported books.

According to book importers, much anticipated books become available in the Kathmandu market within a few weeks of their publication in the West.

“The lockdown is not the main reason why books have not been coming. Some books were coming during the lockdown too,” said a book importer. “It is because of government policy, and we were not in the right frame of mind as a result.”

Not only Mary Trump's book but also Hilary Mantel's The Mirror and the Light, the final part of the trilogy on the life of the 16th century chief minister in the court of King Henry VIII of England, is not available though it was published in March. The first and second books of the trilogy, Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies, won the prestigious Booker Prize, and this one too has been tipped to bag the award.

“In June, I went to purchase Phyllis Chesler’s An American Bride in Kabul. I couldn’t find it at any of the book stores here in the city,” said Rachana Thapa, an avid reader. “It’s not just Chesler’s book that I couldn’t find. In the past six months, I have frequented some of the leading book stores in the city and many of them no longer have the latest books, and they only have very limited choices to choose from. It’s a shame that we no longer seem to have the right to read the latest book or our choice of books.”

This wariness among importers stems from an incident in January. The Department of Revenue Investigation (DRI) office at Pathlaiya stopped a Kathmandu-bound truck carrying a cargo of books belonging to 21 importers after 10 percent customs duty on them had been paid at the border, according to authorities and importers.

“We were taken completely by surprise,” said an importer whose books were among those seized.

None of the half a dozen book importers the Post talked to wanted to reveal their names because of the 'sensitivity' of the issue and fear of 'harassment' by government authorities.

There are two reasons for the DRI’s move. One, the decision was based on a directive from the Department of Customs dated August 30, 2019.

“As per this directive, a product on which 10 percent customs duty is imposed, the average price that the importer pays is maintained at 57 percent of the MRP (maximum retail price). This means we do not recognise any bill that the importer produces which suggests that the cost of the book to the importer is less than 57 percent of the MRP for the purpose of charging customs duty,” said Shisir Ghimire, information officer at the Department of Customs.

Book importers are not happy with the government decision. “This means that if I produce an invoice from an Indian exporter that I bought books at, say, 40 percent of the MRP and got a discount of 60 percent, the bill is not recognised,” said one of the book importers. “The customs duty I pay will show as if I got only 43 percent discount and not 60 percent as the invoice says.”

The second issue is the retail price of the book that the government recognises.

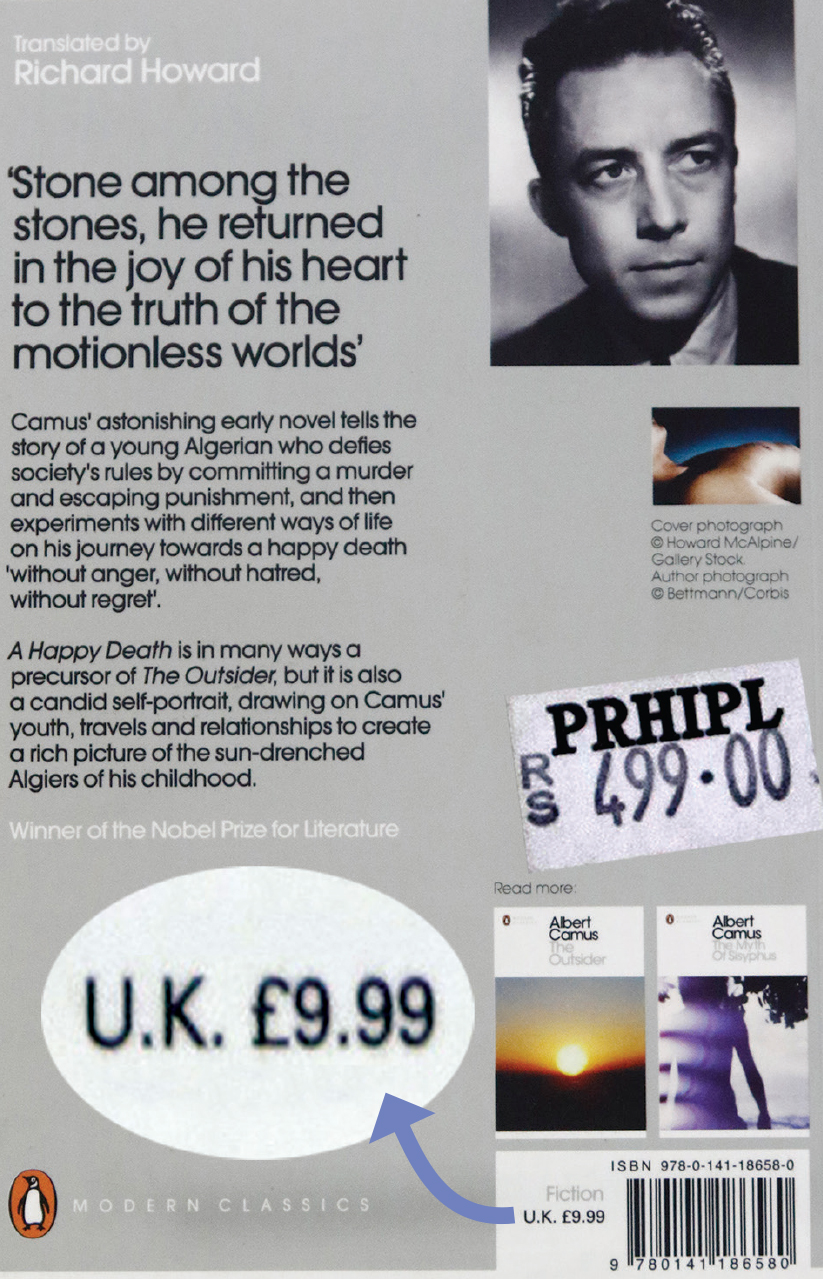

“A majority of the imported books in Nepal come from India because that’s where the regional offices of the world’s leading book publishing houses are located,” said another importer. “Most of the multinational book publishing companies only print British pound and US dollar prices on the book. That’s just how the industry works. To denote a book’s Indian MRP, all they do is put a price sticker showing the Indian MRP on the book.”

“The pricing by publishers is different in different parts of the world depending on the purchasing power of the local public,” another publisher added.

But in January, DRI officials from Pathlaiya said that the sticker price would not be recognised and customs duty would be levied based on the printed price.

“If they don’t want dollar or pound MRPs to be recognised as the MRP, they can import books that are only priced in Indian currency,” said Ghimire. He said booksellers were selling books in Nepal at US dollar or British pound rates.

“They should sell the products at the Indian prices in Nepal, not dollar prices. If the dollar MRP is not official, they should produce proof,” he added. “Importers produce different bills for the same goods, and it is difficult to distinguish between real and fake bills.”

After holding the January consignment for nearly a month, authorities released it after the importers were asked to deposit about Rs3 million, said an official from the DRI, Pathlaiya and book importers.

“Of this amount, importers deposited varying amounts depending on the quantity of books they had imported and the low customs duty they had paid compared to the valuation of the products determined by the valuation rate of 57 percent of the MRP,” said Hom Pandey, section officer of the DRI, Pathlaiya office. “Most of them had paid customs duty based on 50 to 52 percent of the MRP.”

A smaller percentage of the total fine was also the difference in customs duty based on foreign currency and Indian currency price of the books, according to authorities and importers.

The final decision on the issue is still pending, a book importer said.

“We sent a report on the incident to the Department of Revenue Investigation head office in Kathmandu. It can decide whether to send it to the Department of Customs for settlement,” Pandey said.

Meanwhile, the import of books has come down to a trickle, and new books like those by Mary Trump and Hilary Mantel are still unavailable in Kathmandu.

According to Department of Customs data, books, maps, brochures and leaflets worth Rs526.17 million were imported in the fiscal year 2019-20, down from Rs1.08 billion in 2018-19.

Book importers are still rankled by the January decision. “I do not understand why the DRI made that move in January. They seem to have acted on a tip-off,” said an importer.

The Department of Revenue Investigation was brought directly under the Prime Minister’s Office after KP Sharma Oli became prime minister in 2018. Earlier it was under the Ministry of Finance.

Explaining the issue of discounts, an importer said Western publishers send what are called 'remainder' books, in industry parlance, to India at 80 to 90 percent discount. “These books may not be very recent but they still sell,” said an importer. “If I get a book at 80 percent discount, I give buyers a big discount as well.”

He showed a children’s book priced 4 pounds which he was selling for Rs240 to support his claim.

But the Customs Department circular does not recognise a discount bigger than 43 percent, said another book importer.

On the issue of US dollar and British pound versus Indian rupees, another bookstore operator said, “In a bid to resolve this issue, we have urged book publishers to print Indian prices on the book, but we know that not all of them are likely to do so.”

For a bookseller who sells mainly textbooks published in the United Kingdom, this is worrying. “If the current situation persists, I will soon run out of textbooks and won’t be able to import new ones,” he said.

Book importers say the ideal situation would be if the government reversed its decision to impose a 10 percent customs duty on books, a provision that has been continued in the 2020-21 fiscal budget.

"We used to give a 10 percent discount on books to every individual buyer, and a larger discount to every institutional purchase; but we can't do that anymore," said a book importer and distributor.

"Before the 10 percent customs duty was levied, all book importers had to pay was just freight charges to get the books from India to Nepal. But now, after the government imposed customs duty we even have to pay VAT on freight charges. This has increased the cost of books by as much as 18 percent.”

Given the extra costs now for many books, it just becomes very difficult and impractical to sell without exceeding the set retail price, according to more than one importer and retailer. On his recent consignment one importer spent 22.5 percent over the cost of the books on the customs duty he had to pay on the foreign currency price and transport charges.

“After adding other costs like rent and overhead costs, book importers could make a decent profit. We could import books easily and customers could buy them at a cheaper price. It was a win-win situation for everybody,” said another importer.

Last year, after widespread protests against the new customs duty, authorities investigated the accounts of several importers to check for possible income tax fraud, according to an importer. It was like the authorities did this as a consequence of our call to remove the 10 percent customs duty, he added.

“Our accounts are transparent, and the payments we make to exporters in India are made through the bank so everything is out in the open,” said an importer. “But the humiliation and harassment is psychologically crippling.”

“We are just under too much stress,” said another. “We are not in a situation to confront the government.”

Kedar Bhakta Mathema, former vice-chancellor of Tribhuvan University and who has headed different government commissions in the education sector, is baffled. “I don’t understand what is going on,” he said.

“The raid shows that dissent is not respected. A democracy does not function that way,” he added, referring to the initial condemnation from booksellers and the general public to the government’s decision to levy customs duty on books last year.

The reason the government had given for imposing customs duty on books was to protect printing presses in the country. “It is the duty of the government to protect them. They have invested heavily, and they are paying customs duty of 15 to 20 percent on imported paper. Not levying any duty on imported books has not created a level playing field for domestic industry,” said Ghimire of the Department of Customs.

Asked what the impact has been on the printing industry as a result of the customs duty, he said, “Whether this policy has benefited domestic industry is a matter to be studied.”

Meanwhile, imports have come down to a trickle and book importers are choosing the titles they import very carefully.

Not only are the latest books on Trump or fiction not available in Kathmandu, neither can a tome on Nepal entitled Higher Education in Nepal: Policies in Perspective published by famous London-based academic publisher Routledge be found here.

“It seems as if we as a society are going towards ignorance. This is almost like we are going back to Rana times,” said Mathema.

A bookseller expressed his frustration more acutely. “It would have been better if we were selling meat instead of books,” he said.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu