Miscellaneous

The weight of history

Kathmandu is perched on shaky ground; and its residents know it. Over the past millennia of recorded history, dozens of earthquakes—of varying magnitudes—have rumbled through the Valley, often leaving widespread casualties and destruction in their wake. But with each calamity, Kathmandu’s residents have stepped up to the plate, picked up the broken pieces and restored what was lost—its stunning architectural marvels renewed and passed on to the next generation for upkeep.

Sanjit Bhakta Pradhananga

Kathmandu is perched on shaky ground; and its residents know it. Over the past millennia of recorded history, dozens of earthquakes of varying magnitudes have rumbled through the Valley, often leaving widespread casualties and destruction in their wake. But with each calamity, Kathmandu’s residents have stepped up to the plate, picked up the broken pieces and restored what was lost—its architectural marvels renewed and passed on to the next generation for upkeep.

That Kathmandu has internalised that impermanence is a fact of life is perhaps best enshrined in its indigenous architecture. Its towering temples, its sprawling palaces and its cloistered row-houses, after all, weren’t built to last. They were built to be restored and rejuvenated generation after generation—its finer nuances evolving with each new thumbprint.

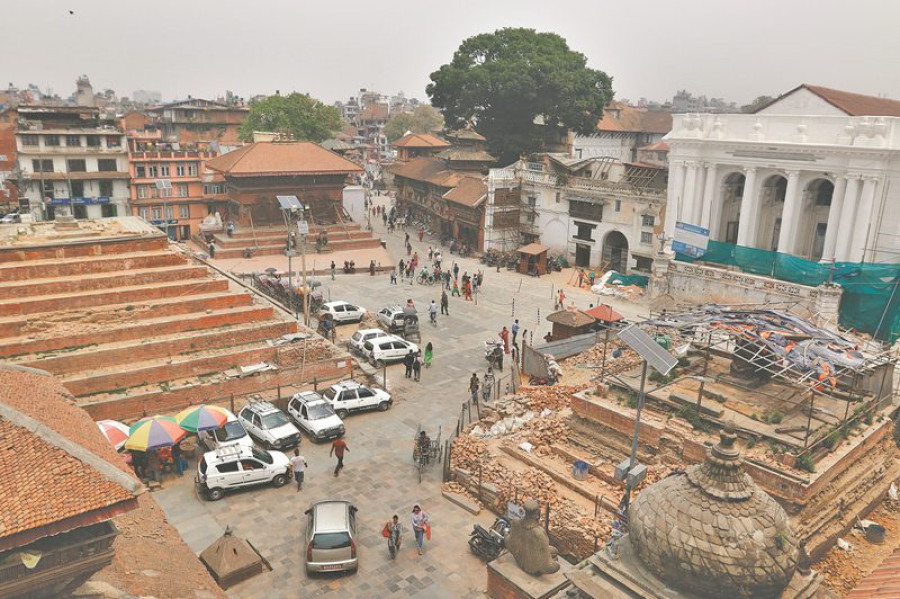

But the 2015 earthquake was different. With the steady erosion of social mechanisms—like the traditional Guthis—that made the continual restoration of ageing public structures possible, the destruction of hundreds of heritage sites in the Valley have, for perhaps the first time, been accompanied by a crippling sense of uncertainty. Caught between a lethargic government and bureaucracy and locals who don’t have the resources (or sometimes will) to undertake massive reconstruction processes, Kathmandu’s heritage sites have been languishing in various states of disrepair.

While it is true that significant progress has been made at some sites in Patan, Bouddha, Bhaktapur and parts of the Kathmandu Durbar Square, the critical question that has flared over the past three years has been how Kathmandu’s heritage should be rebuilt, and who should do it.

While there is little doubt that with the right donors backing them, even the most lethargic of governments can erect new buildings in place of the old, the sense of ownership and attachment that transforms cold, gangly buildings into venerated temples or beloved communal chowks is not so easily transferred. And this begs the question: How will Kathmandu’s residents relate to, interact with, preserve, and pass on heritage sites that they have had little to no part in shaping?

That is the marker by which this generation of renewal of Kathmandu’s heritage will be measured by. Because that, and not the completion of projects—however grand or well done—will echo into the future until the next big one comes rattling Kathmandu’s doors again.

Krishna Mandir, Patan

Changu Narayan

Rani Pokhari

Swayambhu

Basantapur Durbar Square

Bhaktapur Durbar Square

Basantapur Durbar Square

Bhaktapur Durbar Square

Photos: Keshav Thapa

Text: Sanjit Bhakta Pradhananga

16.01°C Kathmandu

16.01°C Kathmandu