Miscellaneous

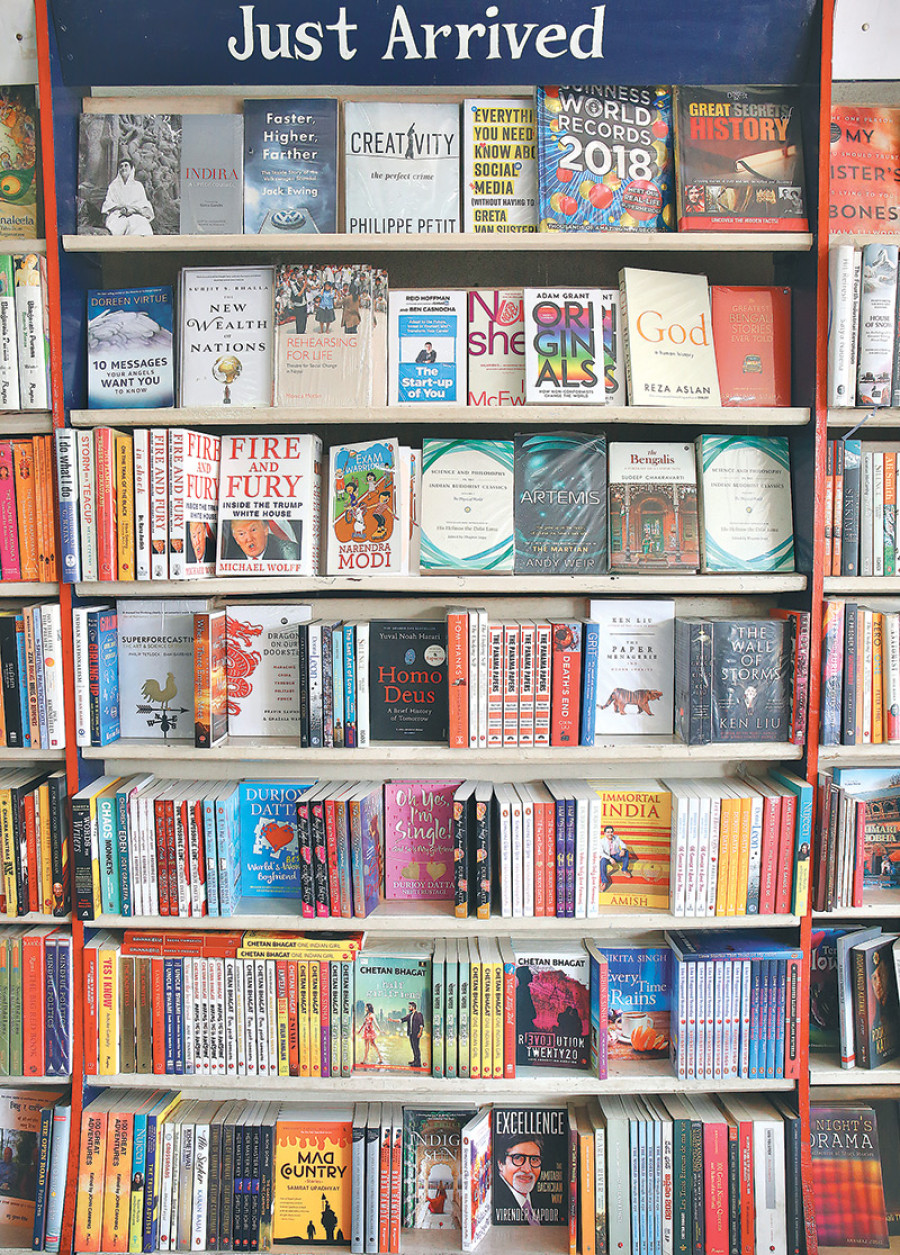

Book rush

Almost half a century before the publication of Bhanubhakta Acharya’s translation of Ramayana—considered widely as the first Nepali bestseller—the Bible had been translated and published in Nepali in 1821 CE.

Sandesh Ghimire

Almost half a century before the publication of Bhanubhakta Acharya’s translation of Ramayana—considered widely as the first Nepali bestseller—the Bible had been translated and published in Nepali in 1821 CE.

“That translated Bible, which is the first book to be published in Nepali, must have been done under the direction of the priest, father Ganga Prasad, in Darjeeling,” says Deepak Aryal, a researcher at the Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya, an organisation that archives books published in the Nepali language, “Contrary to what one might believe, translating a massive text like the Bible could not be possible without help from the Nepali rulers at the time—the Rana family.”

The Bible, which was printed in Sherampur Press in Calcutta, did not circulate more than a few dozen copies. By contrast, Bhanubhakta’s Ramayana, also published from India, went into several reprints.

According to Aryal, around 100,000 copies of the book had circulated in Nepal by 1951, which meant that every single literate household at the time likely had at least one copy of the Ramayana.

Nonetheless, Nepal-based publications remained largely sluggish until the end of the censorious Rana Regime. Out of the 3000 titles published in the Nepali language until 1951, less than 100 titles had been printed within the political boundary of Nepal.

And while, the fall of the Rana Regime brought with it a marked rise in the number of books published in the country, it wasn’t until the turn of the millennium that publishing truly boomed as a viable industry. Thanks to the introduction of modern printing presses and the rise of books as a marketable commodity, the publishing business has become one of the most vibrant industries in the country, “with an approximate annual growth rate of 15 percent,” according to publisher Indra Mani Neupane of Shangrila Books.

Industry insiders peg the origins of this very recent boom to the phenomenal sales of Narayan Wagle’s 2005 novel, Palpasa Café. What this Madan Puraskar-winner did, according to Kiran Shrestha of Nepalaya—the book’s publisher—is that it made books accessible for popular consumption.

“Before we published Palpasa Café, most Nepali books were being sold for less than Rs 100, and many people thought that we were crazy for trying to sell a book for more than twice that amount,” Shrestha says, “But better editing, quality paper, a more readable font, a better cover design and layout helped establish publishing as a profitable venture if packaged in the right way.” Palpasa Café would go on to sell more than 60,000 copies of its Nepali edition, with its 2010 translation outdoing the original by selling north of 150,000 copies.

But beyond just being a book that gripped the public imagination, Palpasa Café’s success also served as a watershed moment for the entire publishing industry. Since the novel first appeared in 2005, more players have entered the market and today 70 publishers and booksellers are registered with the National Booksellers and Publishers Association of Nepal (NBPAN).

As a result, according to Neupane, books from all genres have begun to find a readership in the market. From biographies of business tycoons, politicians, army generals and comedians, to academic books, serious journalistic explorations of social issues, and light hearted young-adult fiction titles—a wide range of genres have been able to carve a niche for themselves among the readers. The industry’s vibrancy is also evident in the fact that numerous book launches are held each week, with publishers competing against each other for public attention.

While the outreach of social media has provided a platform for free publicity, publishers are finding unorthodox ways for promoting their books.

In 2013, FinePrint, a leading publishing house in the country, made headlines by offering Rs 1 million as a book advance to TV personality Vijay Kumar Pandey for his memoir, Khusi.

“You could say we have managed to lead the field when it comes to book promotion in Nepal,” the co-founder of FinePrint, Ajit Baral, shares with the Post, “Apart from the conventional book launches and social media campaigns, we have printed book excerpts, book marks, placed newspaper ads, produced YouTube videos, organised lunches with writers, introduced attractive book offers and started taking in pre-release orders.”

As a result, according to Baral, book launches are no longer the drab events they used to be, but rather have evolved into vibrant social gatherings that draw sizeable crowds, along with eminent speakers and panellists.

Other publishers are also introducing novel ways of getting readers to buy their books, and the publishers agree that competition is helping the publishing market to grow in quality as well as quantity. But despite the meteoric growth, the industry still finds itself among ample hurdles, the biggest of which is it not being able to capitalise on the demand and appetite for books by Nepali writers writing in English.

“A supply of quality editorial professionals, publishing friendly policies, libraries, creative graphic designers would help the publishing industry grow further,” shares Baral, “And the bilateral agreement with India also adds several unnecessary hurdles in exporting our books to India.”

In the Nepal-India Inter-Governmental Committee (IGC), a secretariat level meeting held in December 2013, in Kathmandu, the Nepali side had mentioned that exporters in Nepal faced problems in exporting newspapers and literary books to India, to which the India side assured that the process would be reviewed. However, Nepali publishers say, the export channel has not been eased.

Bidur Dangol at Vajra Books opines that the roadblock in exporting books from Nepal to India has resulted in Nepali writers writing in English choosing to publish their books in India, “There is a big market for Nepali writers in India, and to tap that market, writers prefer to publish in India. That way it is also easier for the book to be marketed in South Asia and the rest of the world as well,” he says, “Importing books from India can be enough of a hassle, exporting a book published in Nepal is a whole another matter altogether.”

Dangol points out that some of the best English titles of the past years, including Manjushree Thapa’s All of Us in Our Own Lives and her translation There’s a Carnival Today, Sagar SJB Rana’s Singha Durbar: The Rise and Fall of the Rana Regime, and Rabi Thapa’s Thamel: Dark Star of Kathmandu, were all published by Indian houses before they found their way to Nepal.

According to Dangol, while an unobstructed policy regarding books would really help Nepali publishers, the market for Nepali books is yet to show any signs of saturation.

“Book publishing has truly taken off because of the rising middle class in Nepal and the corresponding rise in literacy. And as long as that happens, there will be a market to consume the Nepali books. I would say the best years are still ahead of us,” says Dangol.

6.12°C Kathmandu

6.12°C Kathmandu