Miscellaneous

A fresh face for Patan Dhoka

If you happen to pass in or out of Patan Dhoka, Lalitpur, of late, you are bound to encounter at least a few artists busy working on either one of the facades of the gate, painting.

Nhooja Tuladhar

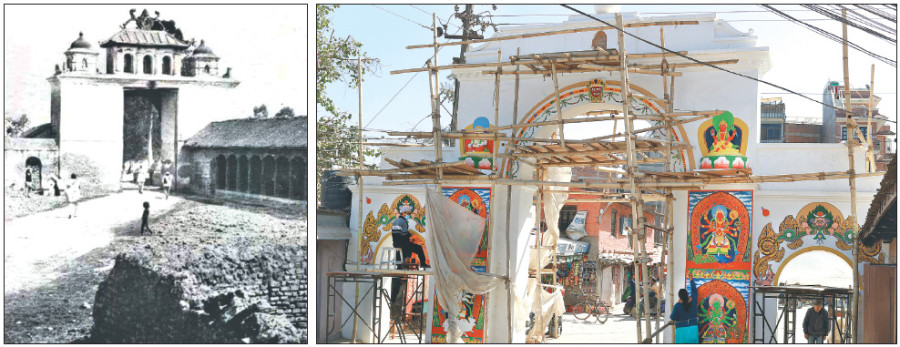

If you happen to pass in or out of Patan Dhoka, Lalitpur, of late, you are bound to encounter at least a few artists busy working on either one of the facades of the gate, painting. On most days, the artists are busy with their cups of paint and brushes—donning shower caps and face masks—painting paubha-style renditions of the Astha Matrika of the tantric Hindu/Buddhist pantheon. The Malla era entrance to the ancient city of Yala, or Patan as we know it today, has received a makeover of late; the gate, within the last three months, has transformed, from a message board that told the Nepal Sambat year, to a larger-than-life work of art.

“The painting of the auspicious signs of the parrot, the eye and the kalash was commissioned for the first time in 1976,” says Shekhar Dangol, President of Shanti Yuwa Club, the initiator of the mural project. “It started when the club decided to paint the Nepal Sambat date on the gate as a form of protest, supporting the Nepal Bhasa Movement, on the first day of the Nepal Sambat new year. And we’d been doing it every year since. This time, though, we decided that it was time to do something different.”

The three auspicious motifs, usually painted on household entrances, are a part of the age-old Newar wall-painting culture done for the wellbeing and prosperity of the families that reside within the walls. Prominent paubha painter, Lok Chitrakar—under whose mentorship the artists are painting the gate—says that the trend of painting these motifs were slightly problematic to begin with, in accordance to traditional culture—as they weren’t supposed to be done in public locations but in personal spaces, exclusively.

“The idea of painting the Asta Matrika came about after we held a number of meetings with culture and Nepal Bhasa scholars,” says Dangol. Then it was just a matter of seeking help from Chitrakar, who has devoted several years to not just create intricately executed paubhas but also to study up on the form and its development through time.

The Asta Matrika—or the mother goddesses—are believed to be celestial beings with immense tantric powers and are positioned in eight different directions—establishing energy centres—around a Newar city to protect its area and the devotees that reside in the periphery. Brahmani, Vaishnavi, Maheshvari, Indrani, Kaumari, Varahi and Chamunda are depicted in the mural, which is scheduled to be completed sometime this month. “Although it’s not possible to position the deities in their exact directions on a cuboid gate, we have at least made sure that the goddesses face the right directions,” says Chitrakar. His students have been studying the iconography and the colour scheme of the depicted deities for religious accuracy; the idea has been to stick to the descriptions of ancient Vedic texts. The artist says the mural draws inspirations from stylistic elements of traditional paubha from different periods between 13th and 19th century. The varied influences are evident in how the backgrounds that surround the central figures are executed in bolder strokes—and dabs—of paint; a stylistic exploit that only came about in paubhas during the turn of the 19th century.

Along with the goddesses are painted four renditions of the Cheppu—an aquatic creature from Bajrayana Buddhist mythology— on all four arches of the gate. The artists have also repainted the four terracotta sculptures of Ganesh and Kumar, which are installed on the top of the gate, on both sides, along with two copper, wax-cast, sculptures of Padmapani Lokeshwors (the Seto and the Rato Machhchendranaths).

While most of those that have witnessed this process of transformation have admired the work initiated by the artists and the youth club, the initiation has not been without criticism. “People come and talk to us when we are painting and while a lot of them thank us for our hard work, some of them also tell us how they like how the gate was before we started,” says Rabin Maharjan, a Patan-based artist who has been leading the project. Some might side with the idea of preserving the structure in its original state, but the current gate that we see has been remodeled several times, the last time after the 1934 earthquake. There is no documentation as to when the gate was first built, but it is known to be the main one among the more than half-a-dozen entrances to the state of Yala.

Pictures that date back to before the 1934 earthquake shows how the gate looked a lot less Victorian than it does now. The previous version was larger and also possessed two Mughal style domes and a gilded roof with a gajur in the centre. Sure, the monument did not possess any painted murals on it in its original state, but artist Chitrakar says that there is nothing wrong with the mural that they are working on as it is an integral part of Kathmandu’s culture. “I still remember painting on homes as well as temples with tempera paint as a young artist. The art of mural making has been practiced in the Valley from a long time back. It’s just that we don’t see much of it these days as it will be very expensive to commission artists for such work in this day and age,” he says.

Then there’s also the hope that the mural will bring other benefits to the community around the gate.

“The mural project not only helps the city from a socio-cultural standpoint but will also be an important aide in improving tourist inflow,” says Dangol. The youth club, has been collaborating with the local community and the municipality in order to initiate activities—mostly related to renovation and restoration—for this very purpose. The youth club’s latest feat has been of working to pave the area with slate, taking charge of its maintenance and also managing parking spaces in the vicinity. “The Lalitpur mayor visited the site a few days back and he has promised that the municipality office will help make sure that the project meets its completion and that the mural is maintained and taken care of.”

Although locals see immense potential in the output of the project in benefiting the area, it seems off that the artists who have already invested more than three months in the project are yet to be adequately remunerated for the work.“We had decided to provide artists with per diems and the target was to complete the project in 45 days. But the work took more time than we thought it would and the costs went up, too,” says Dangol. While the club has already spent about Rs 200,000—in the renovation and white washing of the gate of which a lot of work was done in kind—it still needs at least Rs 800,000 to pay the artists, fit lights and do constructions and fixes that will guarantee a longer life for the painting and the gate.“The club is currently working to secure funds to pay the artists. We want to give them about Rs 1,200 -1,500 for each day’s work.”

“Getting decently paid as an artist is a rarity. But we hope things will improve,” says Maharjan. According to his teacher, a paubha the size of each deity on the gate can be sold for about Rs 500,000. Maharjan adds: “But we are glad that we got this opportunity, from which we have learned a lot and gained much. We are happy that we were able to do something for our city.”

16.32°C Kathmandu

16.32°C Kathmandu