Miscellaneous

Jung Bahadur’s Love for British guns

Most of what we had known about Jung Bahadur Rana’s Europe trip was from a lost diary narrated by his son Padma Jung, published posthumously, in 1909.

Sanyukta Shrestha

Most of what we had known about Jung Bahadur Rana’s Europe trip was from a lost diary narrated by his son Padma Jung, published posthumously, in 1909. Along with the diary, an unnamed co-traveller of Jung Bahadur is also speculated to have published a travelogue, which has also been lost. Fortunately, when a hand-copied version of the travelogue was found, Kamal Mani Dixit published it in 1957, leading to an English translation by John Whelpton in 1983. In the last decade, growing web presence of Western archives has also added a few interesting episodes from what was documented of his Europe trip.

A close observation of Jung’s activities in London reveals that he visited Woolwich—which housed the Royal Military Academy, the Royal Arsenal and a military laboratory at the time—a total of three times, a frequency with which he only paid visits to Queen Victoria. Jung first discovered his interest in the Woolwich site on June 28, when he reviewed the process of manufacturing bullets and the percussion caps that help avoid misfiring in bad weather.

What is not recorded in various recanting of Jung’s travels is his visit to a local family business called James Purdey & Sons, who have been manufacturing guns since 1814. This is because it is neither mentioned in Jung ’s travelogue nor his son Padma Jung’s narrative. But thanks to British surgeon Henry Ambrose Oldfield’s knowledge of English guns, we know he briefly mentioned in his 1880 publication that Jung was in possession of Purdey’s pistols in 1851, just after his return from London.

Having moved from 314½ Oxford Street, where Jung would have visited them, Purdey’s Guns & Rifle Makers have kept their sales record intact from as early as 1818. This makes it possible to trace some important transactions made by Jung in person between the end of May and mid-August of 1850.

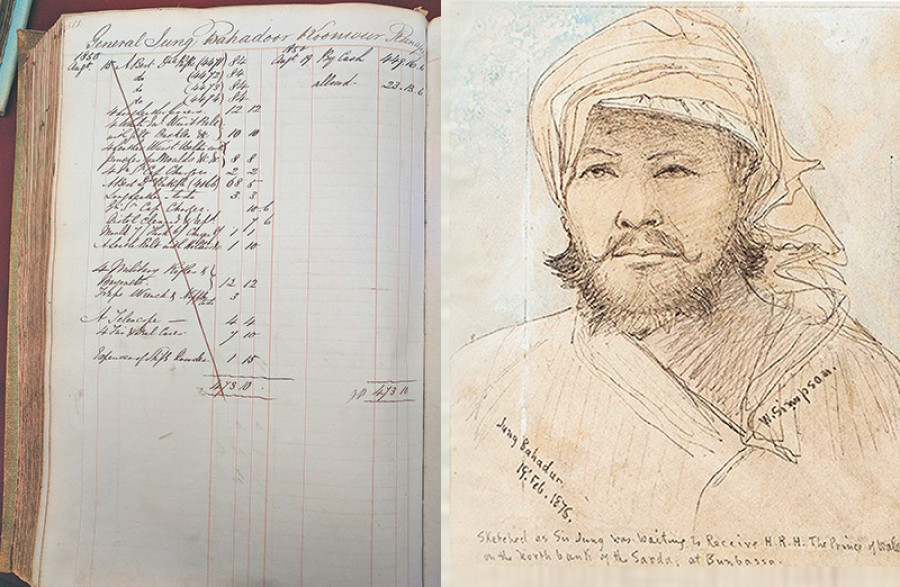

On May 31, 1850, Jung Bahadur first visited Purdey’s where his account was opened on page 379 of ‘Ledger E 1847’ under the name of ‘General Jung Bahadoor Koonwur Ranajee’. On this day, he must have been received by none other than a 66-year-old James Purdey Sr, the founder of Purdey’s, who had established himself as London’s best gun maker—one of his clients being Queen Victoria herself. Jung’s title in the accountholder’s name aligns well with the fact that he was not yet a ‘Maharaja’, in contrary to those who believe he took up the title of ‘Rana’ after a Persian lady’s advice. King Rajendra Bikram Shah had actually conferred him the title of ‘Ranaji’ publicly in 1846, according to Oldfield’s account.

On this day, Jung made a total purchase of 23 guns—pistols and rifles—enough to arm all the high ranking members of his team of 41, if we exclude the four cooks, 12 domestic servants and 10 assistants as listed by Padma Jung. This visit to the gun shop seems to be quite a confidential one, or at least less hyped, because Rana is believed to have stayed back at his guest house, Richmond Terrace, while rest of his brothers, including Jagat Shamsher, went to hear oratories at Exeter Hall, accompanied by Captain Cavenagh. Cavenagh was Jung’s official translator according to the India News published from London. So if Cavenagh was not with Jung on May 31, how did he communicate with the gun maker James Purdey? Although Lieutenant Lal Singh Khatri is known to have learnt English from British resident Hodgson in early 1840s, how would he work around the local West London accent within three days of his arrival?

Could it have been the enigmatic Moti Lal Singh, who, contrary to popular belief, is considered to be the first Nepali on record to have stepped on the British islands? Moti Lal Singh was first brought to light to Nepali readers by Bishwo Poudel through his September 2010 Himal Magazine article ‘Birsiyeka Moti Lal’ and was further researched by Krishna Prasad Adhikari in his 2013 book ‘Belayat Ma Pahilo Nepali Moti Lal Singh ko Rahasyamaya Jeevan’. Born in Bhaktapur, Moti Lal had fought as a 19-year-old in the Anglo-Nepali war. After being captured and imprisoned, he was later recruited in the British Army in 1815. Soon after, he moved from Calcutta to England where he was spending his later life as a sweeper at St Paul’s churchyard. While both Poudel and Adhikari focus on Nepali translation of Moti Lal’s original article published in London’s New Monthly Magazine in July 1850, they leave their readers somewhat uncertain of when exactly it was that Moti Lal first met Jung Bahadur.

The kind of gun that Jung Bahadur bought from Purdey's & Sons Co., London.

Moti Lal starts section 4 of his article by talking about an unexpected encounter with the high ranking Nepali team in London when they were visiting ‘John Company’ in Leadenhall Street. When collated with Padma Jung’s narrative, the Company visit can be dated to May 27, 1850, which makes it likely that Jung was accompanied by Moti Lal to Purdey’s gun shop as well on May 31.

On June 3, a lump sum payment of £938 for Jung’s first transaction is recorded at Purdey. A cash payment was otherwise less frequent at the time, and the payment date is relatively close to the order date as well. As expected, the account’s closing signatory bear the initials of ‘JP’—James Purdey. Later, on June 6, Rana made an additional purchase of five guns and rifles, and paid for it on July 1 with £339 in cash.

A day before this, on June 30, Jung accepted an invitation by the first Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley, at his official residence. Although already a national hero, owing to his victory over Napoleon in the famous Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Jung seems to have been less than impressed by the Duke of Wellington, who he mispronounced as ‘Duk-ulan-than’, a derogatory term believed to have entered the Nepali diction from this day, and used till date to qualify someone who is a show-off and of little substance.. To start with, Dixit’s reprint of the travelogue leaves Duke’s misspelt name as ‘Dukwailund’.

While Jung’s second visit to Woolwich was on July 10 for an inspection of the repository and the arsenal, by July 19, again, he is recorded as purchasing six more rifles and pistols with a lump sum cash of £604.16, as per page 380 of Purdey’s ledger ‘E’. This time around, Jung seems to have purchased a lot more accessories, ranging from mahogany cases to gold embossing of Jung’s name on the weapons.

Following his study of percussion caps in Woolwich, which were not introduced in Nepal until early 1850s, he is seen adding to his Purdey’s orders, as many as 200,000 best caps, 50,000 pistol caps, and 10,000 Smith’s copper caps. The guns purchased on July 19 were relatively cheaper in price as they were second hand; probably meant for guards and lower ranking officers.

Jung’s third and last visit to Woolwich was on July 23, perhaps to make sure he had collected most of the information regarding arms and ammunitions of the British. As Cavenagh remarked in his 1851 book, ‘Rough Notes on the State of Nepal, its Government, Army and Resources’, Nepal’s artillery included chiefly lead balls as they were ‘unable to cast iron’, and Jung Bahadur had no success with the art of manufacturing fuses even after devoting much time ‘to ascertain the exact proportions of the ingredients used in preparing the composition’. On August 15, Jung managed to make a last visit to Purdey’s to purchase five more custom rifles of the best quality for a total of £449.16, paid for later on August 19.

Jung is reported to have spent up to £1,000 easily on every other item, a habit which gave him the name ‘Hippopotamus’ among the local Brits. His total expenses for Purdey’s guns is £2,330. Considering the UK inflation rate since 1850, and the current Nepali exchange rate in 2017, its current value is £295,027 or nearly NRs 42 million.

From Oldfield’s memoirs of 1851 to Daniel Wright’s 1856 History of Nepal, published in 1856; they all maintain a steady currency exchange rate of NRs 10 for a Pound Sterling in the early 1850s, which converts Jung’s 1850 London arms expenses to NRs 23,300. If Brian Hodgson’s 1834 calculations are anything to go by, this amount was simply one-third of the annual revenue from just the sale of elephants and ivory from the Tarai. Moreover, in a letter from Paris dated August 1850, Jung proposeds to raise NRs 52,000 from seven districts between Udiya and Mechi in order to cover the expenses of his Europe journey. India News of July 1850 rightly expressed, ‘Our Nepalese guests … have spent their money among us with a liberality amounting to profusion’.

The mystery now is what was Jung’s plan with all these arms? While the Nepal army’s in-hand resources were limited to 300 guns, of which 160 were retained at the Capital according to Cavanaugh’s 1851 account, Nepal had reportedly sent 500 artillery men with as less as just 24 guns during the British campaign to suppress the Indian mutiny in 1857. Even the 1855 Nepal-Tibet war, headed by Jung himself, boasted of a 600-strong regiment with only 12 guns! However, shooting excursions to the Tarai would call for as many as 50 guns, as was the case with Jung’s December 1848 expedition with 32,000 soldiers. As a connoisseur of the world’s best arms and ammunition, Jung is likely to have been an avid collector who would enjoy showing off, especially to impress his British co-hunters.

Almost two years after his return to Nepal, Jung made an offshore order to Purdey’s for an additional 10 rifles. In November 1852, the order was received with various diagrammatic details in a workshop’s notebook, possibly in Calcutta, and now preserved in their London store. This hardback notebook titled ‘Gun Details 1851-1868’ has ‘Jung Bahadoor’ written on page 40 and ‘General Jugget Shumsher ’on page 41. Jung’s brother Jagat’s order is for only two rifles and a gold watch.

Special instruction for Jung’s order reads ‘the lighter the better but very strong & serviceable for Elephants Rhinoceros’, which further strengthens our guess the guns were procured primarily for hunting in the Tarai. On May 24, 1852, Jung Bahadur had also started the custom of 21-guns salute in honour of Queen Victoria’s birthday, followed by other public demonstrations. Also, Jung’s celebrated acquaintance from England, Duke of Wellington, aka Dukulanthan, died on September 14 the same year, which Jung mourned by an 83-minute gun-salute, to match the English national hero’s age in years.

While the corresponding London entry for his last order can be found on page 235 of ‘Ledger F 1852’, both Jung and Jagat’s orders were delivered on January 20, 1854, when Nepal was preparing for a war against Tibet. This time, the invoice includes costs for freight, transit and insurance too, which were paid on April 30, 1855, through bank bills by Jung for £796.14 and Jagat for £112.4. Around two months before this date, Nepal-Tibet war had already started with more than 50,000 Nepalis fighting with only 36 guns.

The total of 51 historic Purdey’s guns could still be traced through their serial number engravings in the museums and private collections of Nepal. The last batch of 10 rifles from 1854 will even have JB1 to JB5 engraved within a diamond shape. The thousands of pistol caps will also have Jung’s name engraved down their bottoms. A full page after Jung’s account in the Purdey’s ledger is unusually left blank in anticipation of a comeback by one of its best buyers from the mid 19th century. What other traces left by Jung Bahadur that are still lying around unnoticed in London and beyond, is something for us to find out before sketching a complete biography of one of the most popular figures from pre-modern Nepal.

Acknowledgement: Nicholas Harlow (Archivist, James Purdey& Sons),researchers/authors Dr John Whelpton, Dr Krishna Prasad Adhikari, Dr Bal Gopal Shrestha,Dr Stefanie Lotter, Subodh Shumsher Rana and Dipesh Risal.

The author is a researcher of Nepali art history and a software developer based out of London, UK.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu