Miscellaneous

The tussle for Kasthamandap

At their small office overlooking Kasthamandap, a group of young volunteers for the Campaign to Rebuild Kasthamandap are huddled in a circle, discussing the flurry of events that have taken place at the seventh century monument this week.

Sanjit Bhakta Pradhananga

At their small office overlooking Kasthamandap, a group of young volunteers for the Campaign to Rebuild Kasthamandap are huddled in a circle, discussing the flurry of events that have taken place at the seventh century monument this week. The room, which is usually abuzz with activity, is starkly muted today and a heavy cloud of frustration looms large. Every few minutes, a volunteer rises, peeks out the window, sighs, and sits back down.

Across the street, at Kasthamandap, five workers from the Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) are rushing to create a makeshift cover for the monument’s exposed foundation out of tarpaulins. The group had arrived, unannounced, the day before and begun to dismantle the bamboo structures erected by the volunteers in a bid to build a cover themselves. Despite the monsoon downpour, working with uncharacteristic speed, the task was completed within 24 hours. Prior to this week, Kasthamandap’s 1,400-year-old foundation had remained exposed to the elements since a joint excavation was carried out by the Department of Archaeology (DoA) and Durham University last fall.

“So, why the sudden interest now?” asks Birendra Bhakta Shrestha, the chairman of the Campaign to Rebuild Kasthamandap—a community-led initiative that was recently handed over the task of rebuilding the monument, “In the two years since the earthquake, the authorities showed little interest in securing and salvaging what was left of Kasthamandap. Now that the Campaign was just about to complete the first phase of the rebuilding (protecting the foundation with a temporary structure before the onset of monsoon), we’ve been obstructed by this uninvited intervention.This is tantamount to vandalism.”

Shrestha argues that the reconstruction of Kasthamandap is no longer within KMC’s jurisdiction.

On May 12, an agreement was signed between four parties—National Reconstruction Authority (NRA), the Department of Archaeology (DoA), Kathmandu Metropolitan City (KMC) and the Campaign to Rebuild Kasthamandap—that handed the Campaign the responsibility of rebuilding Kasthamandap. The agreement was signed by Yamalal Bhusal (Joint Secretary of the NRA), Besh Narayan Dahal (Director General of the DoA), Ishwor Raj Poudel (Executive Officer of the KMC) and Birendra Bhakta Shrestha (Chairman of the Campaign to Rebuild Kasthamandap).

Nabindra Raj Joshi, the then Minister for Industry and the parliamentary representative for the Durbar Square area, was also present at the signing, and had pledged that provisions would be made for high-quality timber required for the rebuild to be provided through the Timber Corporation. At the event, NRA’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Govinda Raj Pokharel had hailed the initiative as a “model project” that would “safeguard the originality of Nepali architecture, and the history and culture of the community.”

Yet just six-weeks later, the three-year project appeared to have been plunged into uncertainty this week with the KMC unilaterally intervening in the project, which the Campaign argues is against the spirit of the four-party agreement.

‘Hard-won privilege’

The Memorandum of Understanding signed in May was itself the result of a two-year-long canvassing by the Campaign.

In light of the government’s lethargic response to the rebuilding of heritage sites destroyed by the 2015 earthquake, locals had launched a campaign to rebuild the iconic Kasthamandap through a community initiative that prioritised the use of local resources and traditional building methods.

Then, organising a ceremonial oath at 11:56 am on April 25 this year, exactly two years after the Gorkha Earthquake killed almost 9,000 and damaged hundreds of heritage sites across the country, the Campaign made a public pledge to reclaim the stuttering rebuilding process and to charge it with local fervour and community ownership.

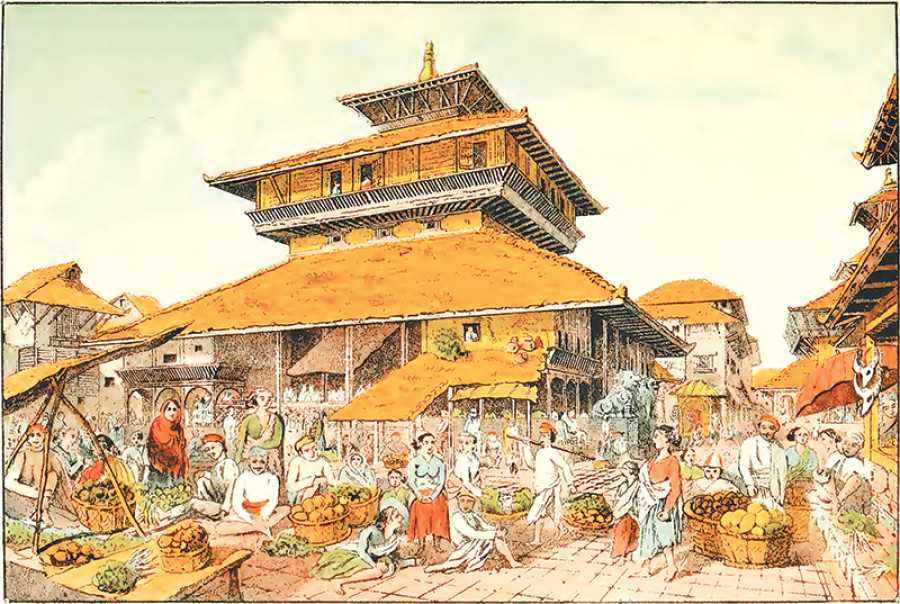

Kasthamandap is the oldest public building in Kathmandu Valley. Serving both religious and secular functions for over a millennium, the wooden pavilion is misconceived as having been built by Laxmi Narsingh Malla in the 17th century.

Other estimates had placed the structure as a 12th century monument. But the joint excavation conducted last year pushed Kasthamandap’s dates back by five centuries, confirming that the foundations dated to the seventh century.

But more than just a physical structure, Kasthamandap also holds immense cultural and symbolic importance for Kathmandu. Lying at the crossroads of two ancient trans-Himalayan trade routes that connected China and Tibet to India, Kathmandu’s very name is derived from Kasthamandap.

Which is why, Mary S Slusser, a pre-eminent historian and chronicler, has described Kasthamandap as the most important heritage site of the Valley. In an article Why Kasthamandap Matters by author Dipesh Risal, published after the earthquakes brought the pavilion down, she was quoted as saying, “Kasthamandap is Nepal’s heritage defined, a witness to its history and evolution as a nation for almost a thousand years—and likely more. No other traditional building in Nepal could compete in size, antiquity or cultural impact. It must not be allowed to perish.”

The government’s efforts to rebuild the Kasthamandap after the quakes, however, were marred by missteps. Last year when the Department of Archaeology, the government body charged with overseeing the sites of historical importance, green-lighted architectural plans for rebuilding Kasthamandap, it drew flak from locals and heritage conservationists alike for including steel, industrial glue and even concrete in the blueprint. Stakeholders at the time had argued that the proposed plans went against the DOA’s own heritage conservation guidelines and had been drafted without due consideration for the reuse of structural elements salvaged after the quakes.

In 2015, the Gorkha Earthquake destroyed 753 heritage sites in the country and damaged many more.

In the two years since, the government’s efforts to rebuild heritage sites have been obstructed by protests from local communities who accuse the authorities of lack of transparency, a disregard for traditional building methods and of ramming through projects through the “lowest-bidder tender system” which hands out lucrative rebuilding projects to contractors without taking stock of their expertise or previous experience. Rebuilding projects, including of the historic Rani Pokhari, Dus Avatar Temple and Jaisi Dega, have halted this year in light of vocal local opposition.

“So, it was not like we just grabbed random people from the streets and made them sign the agreement. Its signatories were top-level bureaucrats, accountable to the people,” Shrestha says, “The responsibility of rebuilding Kasthamandap was a hard-won privilege, and we intend to honour our end and hold the others to theirs.”

What agreement?

When the four-way agreement was penned, it had been hailed from all quarters as a unique public-private partnership model that could potentially be replicated elsewhere—a testament to what could be achieved if all stakeholders strove towards a common goal. But just a short month later, it has come to highlight how entangled and ‘red-taped’ heritage conservation is.

The Campaign claims jurisdiction over the rebuilding on the virtue of the signed MoU, KMC on the virtue that it is charged with the oversight and operation of public assets of the Metropolitan area. Matters of historical importance also fall under the Department of Archaeology’s control, while all rebuilding efforts following the 2015 quakes are being overseen by the National Reconstruction Authority.

This has in turn sown seeds for confusion regarding what each party’s duties and responsibilities are. For instance, KMC Ward-20 Chairman, Rajendra Manandhar, who was voted into office in the recent local-level elections by a razor-thin margin, claimed ignorance over any agreements that were signed. “I have yet to receive any official information regarding the issue.” he said. Ward-20 also has jurisdiction over Kasthamandap—as it demarks its northern boundary—even though the office has so far refrained from wading into the fray.

But more tellingly, Udaya Pasakhala, who heads KMC’s Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square Conservation Program, too claimed that he is yet to receive written documents proving the agreement was signed. “I have been requesting the Campaign to provide the necessary documents, but am yet to receive them,” he said in a conversation with the Post. When pressed on why he has not requested the documents from KMC itself—a signatory to the agreement—or why he had previously handed over the keys to the monument but is refusing to do so now, he replied, “It is the Campaign that wants access to Kasthamandap; it is they who should bring copies of the agreement. As far as I know, the rebuilding of Kasthamandap was to be done through a tender process. That process is ongoing.”

The Conservation Programme locked Kasthamandap’s premises earlier this week, citing that complaints had been lodged by other locals in the area, and on Wednesday authorised the dismantling of the tarpaulin cover erected by the Campaign’s volunteers.

The ‘Danger List’ and the redtape

This latest controversy comes at a time when Kathmandu’s fallen monuments are facing the imminent danger of losing their status as World Heritage Sites.

On June 2, a report published by UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee recommended that the cultural heritage sites of Kathmandu Valley be enlisted in the “danger list” as a result of the government’s failure to reconstruct heritage sites following the 2015 earthquakes. The report, prepared by the Reactive Monitoring mission that was in Kathmandu from March 20 to 25, concluded that “the best way forward for the protection and recovery of the property is that it be placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger.” According to the report, a combination of issues, including the lack of documentation of the damage to monuments, use of inappropriate construction methods, lack of monitoring of works in progress, and the poor coordination between the various stakeholders, were major threats to Kathmandu’s heritage sites.

The report was published in light of the 41st session of the World Heritage Committee set to convene in Krakow, Poland starting July 2.

The World Heritage Convention is an international convention adopted by UNESCO aimed at conserving the world’s most outstanding heritage sites. The World Heritage Committee—a 21-member body—decides which sites make the list of World Heritage Sites. The Committee also publishes a second list: the “List of World Heritage in Danger.” And while, the enlisting of a heritage site on the list isn’t itself calamitous—as in most cases it is followed by international interventions—it comes with the obvious embarrassment for the host nation and the danger of the site losing its World Heritage status.

But most of all, of the people losing an entire link to their history.

‘Living heritage not a museum’

Back at the Campaign for Kasthamandap Reconstruction office, Suman Shrestha, an active volunteer and a member of the Campaign’s 15-person steering committee, cedes that the initiative had foreseen that disagreements would naturally arise in a reconstruction project of this scale. “With so many stakeholders, it is not possible to always see eye-to-eye,” he says, “Which is why, we have always tried to move ahead through a consensus. But this doesn’t mean that the KMC can unilaterally intervene, citing complaints, without first even mentioning to us that grievances have been lodged.”

Govinda Raj Pokharel, the CEO of the National Reconstruction Authority—the agency the agreement appoints as the final arbitrator should disagreements between two or more parties arise—also expressed concern over this week’s development. Weighing in on the issue he said, “The NRA recognises that these monuments are a part of the Valley’s living heritage and are not museums. It is important that the community have ownership over the rebuilding process. Decisions should be made through discussions, not through bullying or bypassing another party.” Pokharel confirmed that the NRA has received a letter from the Campaign about the recent turn of events and would be conducting a follow-up before calling all parties to the table.

The Campaign too is maintaining calm, according to Birendra Bhakta Shrestha. “It could be a misunderstanding, with the KMC just recently transitioning from a 20-year ‘bureaucratic regime’. But if there is something more sinister afoot, we are ready to stand our ground. Heritage reconstruction should not be done through the lowest-bidder tendering system; and Kasthamandap is where we are drawing the line.”

***

Timeline for Kasthamandap’s Rebuild

April 25, 2015: A 7.8 magnitude earthquake rocks Nepal, killing almost 9,000 people, and bringing down 753 heritage sites. Kasthamandap is destroyed in the quake, and 10 people die at the site.

May, 2015: Local communities express alarm over the use of excavators to clear out the rubble at Kasthamandap, worried that it would cause irreparable damage to the building’s foundation.

January 17, 2016: The government initiates its rebuilding campaign with a symbolic event held at Rani Pokhari in the Capital.

August 27, 2016: The reconstruction of the rebuilding of the 17th century Rani Pokhari is halted after local protest over the use of steel and concrete, against heritage preservation guidelines. The protest galvanise communities, experts and conservation enthusiasts against government apathy and lack of oversight.

December 24, 2016: A joint excavation by the DoA and Durham University push back the dates for Kasthamandap by five centuries, establishing that the structure was built in the 7th century.

April 25, 2017: The Campaign to Rebuild Kasthamandap make a public pledge to rebuild Kasthamandap through a community-led initiative.

May 12, 2017: A four-way agreement is signed between the NRA, DOA, KMC and the Campaign, handing over the responsibility of rebuilding Kasthamandap to the Campaign. A three-year, Rs 20 Crore project is outlined.

June 18, 2017: Campaign volunteers begin erecting a temporary structure out of bamboos to safeguard Kasthamandap’s foundation from the approaching monsoon.

June 26, 2017: KMC’s Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square Conservation Program padlocks the Kasthamandap premises, citing complaints from locals.

June 28, 2017: KMC workers dismantle the bamboo structure erected by the Campaign and replace it with tarpaulins.

16.01°C Kathmandu

16.01°C Kathmandu