Miscellaneous

The business of sequels

Five years ago, when director Nischal Basnet’s debut feature directorial Loot released, it changed the discourse of the Nepali film industry.

Timothy Aryal

Five years ago, when director Nischal Basnet’s debut feature directorial Loot released, it changed the discourse of the Nepali film industry.

The film defied the traditional modus operandi—majority of films even today invariably include a few fight sequences and songs, borrowed from the formulaic bollywood films of the 90’s.

The flick, about a small-time gang that aims to make it big by robbing a bank, had its share of profanity, but that profanity was at the very heart of the film’s originality. It boasted dialogues that one might overhear while walking through a galli, bringing to the screen a sense of realism seldom explored before in the industry.

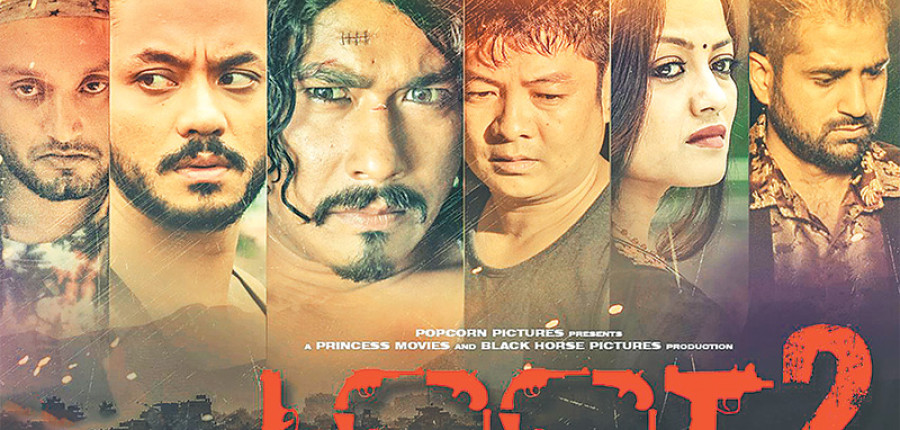

A sequel to the blockbuster was released last year, and it raked in a whopping 60 million in the first week of its release.

But critically, the film was considered feeble. One reviewer wrote: “Loot 2 is very much the sort of project in which the aspiration to ‘coolness’, or a specific loutish version of that, overrides everything, from plot to performance, culminating in an over-the-top, overlong and overindulgent film.”

So was the sequel made only to amass money? Its director Nischal Basnet says no. “The way Loot ended, it was necessary to stretch the story. Because the sequel starts where the prequel ends, we were obliged to continue with the name,” Basnet says. “Of course, the name is a plus point. But that doesn’t mean that the film was named only to cash in on the previous success.”

In an industry that is still struggling to find a voice of its own, the recent rush to make sequels to films that have done decent business continues to rise.

But then, how useful are sequels that repeat and entrench previous plotlines and formulas?

A sequel to 2015’s hit Prem Geet is all set to release this month. Naai Nabhannu La 4 released last year. And Chhakka Panja 2—sequel to Nepal’s highest ever grossing movie—its producer Deepak Raj Giri informed, is currently into post-production.

Giri says that Chhakka Panja 2, apart from its name and characters, has nothing to do with Chhakka Panja. “Of course, every sequel is made because the prequel was a hit. We are no exception. And then, when a sequel is made, half of your publicity expense is saved.”

He is honest about the project: that the producers hope to cash in on the prequel’s fame. “If it was, say, Chhaya, instead of Chhakka Panja, then we would have to invest some time and energy to reach out to the audience.

But since its Chhakka Panja, it’s a plus point that everyone who has watched Chhakka Panja will get attracted to it by default.”

Chhakka Panja 2, says Giri, revolves around a different story, set in different circumstances. “Although the characters’ names remain unaltered, the story is entirely different and virtually has nothing to do with the prequel.”

The business of sequels is nothing new to world cinema. In Hollywood for instance, Fast and the Furious franchise have spawned eight movies.

American film historian Mark Harris wrote a couple of years ago about how the independent films are sucked in by the heat of franchise movies: “Movies are no longer about the thing; they’re about the next thing, the tease, the Easter egg, the post-credit sequence, the promise of a future at which the moment we’re in can only hint.”

In the same spirit, not only are Nepali directors looking to cash in on recent successes, they are banking on reviving their old classic as well.

For instance, Tulsi Ghimire’s Darpan Chhaya 2 bombed at the box office last year. Director Ghimire has said that the film, although it borrows name from 2001 cult classic, was a completely different tale.

Regardless, it was only able to muster a meager performance in box office and was lambasted on the critical front—a stain no doubt on the good name of the prequel.

Kumar Bhattarai, a film blogger and director of the film Utsav, says that the current trend of sequels is a manifestation of cinema’s proliferation as a business rather than an art form.

“Sequels anywhere around the world are made to make money. The very fact that a sequel is made is that it saves a heavy amount on publicity expenses.

When I saw Loot 2, I didn’t think the story was something that needed to be continued.”

He concludes: “Sequels don’t in any way contribute to the development of a film industry.”

American film director Francis Ford Coppola’s saying about sequels especially rings true. “Sequels are not done for the audience or cinema or the filmmakers. It’s for the distributor. The film becomes a brand.”

If one is willing to believe that a film is about a certain idea or a style that the filmmaker wants to explore, more than about the money, the matter of sequel should be looked just through the monetary lenses. But once in a while, a sequel comes and gathers the imagination of the entire moviegoing audience overshadowing the feat of other, small-scale but decent movies. And if sequels rarely work, more so in Nepal, why make them at all?

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu