Miscellaneous

Yalung

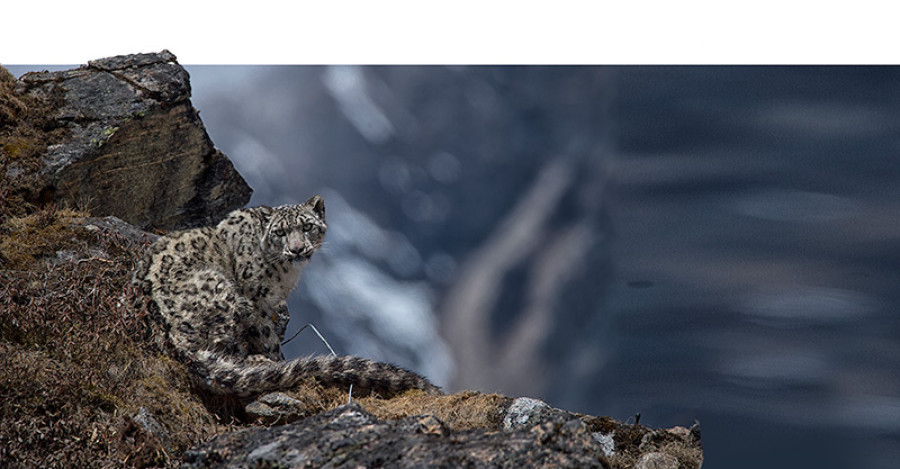

The only certainty about tracking a snow leopard is the uncertainty. These solitary and secretive cats are not called the “ghost of the mountain” without reason—no matter how much you prepare, you are almost always pointing in the dark.

Samundra Subba

The only certainty about tracking a snow leopard is the uncertainty. These solitary and secretive cats are not called the “ghost of the mountain” without reason—no matter how much you prepare, you are almost always pointing in the dark. During every expedition, hope is the operative word. Yet, there we were in Rajmer—a sweeping valley, five days walk north of Taplejung— ‘hoping’ that a cat would put its foot through a small trap laid amid the vast Himalayan landscape.

In fact, just getting to Rajmer is a mission in itself. A 45-minute flight from the Capital and an eight hour drive to Taplejung is merely the start. Then on, the only way forward is on foot. And while the trek weaves through undulating hills, picturesque valleys and steep river gorges—the landscape slowly changing from dense forest of alder, oak and juniper to rugged and barren alpine terrain—you can’t help but internalise that the snow leopard doesn’t want to be found.

Our party—a band of scientists, researchers and conservationists from WWF Nepal, the National Trust for Nature Conservation and the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area Management Council (KCAMC)—arrived at Rajmer in early May in view of collaring a snow leopard under the government’s Snow Leopard Conservation Program. As part of the programme, three other snow leopards—two male and one female—have been successfully tagged with GPS satellite collars in past years.

Between 5 and 7 of May, a hotel room in Ramjer became our control station where we were to receive signals from 24 strategically laid out traps attached to radio transmitters. These traps—called the Aldrich Foothold Snare—clamp the foot of an animal, then transmit a signal when they try to escape. Once the animal is caught, our main communication tower would receive a signal but until then all we could do was wait and watch. For how long, no one could tell. There was a reason our expedition commenced only after a small spiritual ceremony was held, as per local beliefs, to grant us luck and safety. Stationed at a glacial valley at 4500 m, deep in the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area, there were little doubts that we were going to need it.

The snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is a large cat native to the mountainous regions of South and Central Asia. Elusive and secretive, the species is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. A 2013 report places their population at between 3921-6290 in the wild. Nepal’s population, according to the Snow Leopard Action Plan, hovers between 301-400 cats. Called the Semoh by the locals of the Kanchenjunga region, snow leopards are viewed relatively positively, with retaliatory killings by shepherds rare, if reported. And while poaching for body parts remains an ever present threat, habitat shrinkage because of global warming and conflicts with humans continues to remain the main cause for concern for their future.

Discussing with the locals and based on some scientific evidences from previous monitorings, we identified passageways of snow leopard entering and exiting the Ramjer valley, then fanned out to lay the traps trying to cover all possible natural corridors.

Citizen scientists, the locals who trained with us and were part of the team, were recurrently checking whether any of the traps had been triggered from the very first day they were laid. But, with absolutely no signs of snow leopard movement in the camera traps and heavy snowfall to boot, our prospects, admittedly, were rather dim. Then, just like that, an alarm was triggered for a trap set on a mountain ridge two kilometres from our station.

This was my third encounter with a snow leopard in the wild, however, every time, you live the experience anew. Yet, with no time to lose, the tranquiliser was prepared and the dart found its target in a single shot. The snow leopard was then immediately hauled in a stretcher to a safer site. We carefully placed a GPS collar on her neck and checked her vitals and measurements. She was a healthy female snow leopard around two years old with normal body condition and weighed 30 kg and was 165 cm in length.

Wrapping up the whole operation in about 40 minutes, the leopard quickly began reviving once the tranquiliser’s antidote began to take effect. Then, just as quickly as it entered our world, it slid back into its own. Just before she left, however, the locals named her Yalung, after the sacred mountain Yalung Khang—a peaceful sentinel forever overlooking the region.

Yalung became the second female snow leopard and the fourth one to be collared in Nepal’s eastern snow leopard conservation complex in the past four years. The information researchers will receive from her collar will help identify critical corridors, compliment existing snow leopard science and research and contribute towards understanding deeper trans-boundary linkages in the future. They will also contribute to understanding spatial movements, ecological and climate resilient habitats in the landscape.

Now, a few weeks later, back at my desk, my only remaining connection with Yalung is the GPS locations I receive from her collar. We humans have tracked and followed animals since our hunting and gathering days, only now our intention is not to kill but to conserve. And with the Himalayas, and its way of life—of both humans and animals—rapidly changing, Yalung and her future cubs will need all the help they can get.

- Subba is a research officer with WWF Nepal

9.89°C Kathmandu

9.89°C Kathmandu