Miscellaneous

The medieval mall

It is ironic that the word ‘Maru’ in Nepal Bhasa literally translates to ‘does not have’, because this traditional neighbourhood, 300 metres southwest of the Kathmandu Durbar Square,

Monalisa Maharjan

It is ironic that the word ‘Maru’ in Nepal Bhasa literally translates to ‘does not have’, because this traditional neighbourhood, 300 metres southwest of the Kathmandu Durbar Square, it would appear, has just about everything to offer. Busy and bustling throughout the year, Maru is more than just the southern entry point into Basantapur; it is a vibrant community that still perpetuates snatches of Old Kathmandu—a testament of its ability to change and morph itself according to the pushes and pulls of ever-changing time.

Strolling down Maru on a crisp, pleasant spring morning, you are instantly arrested by the frenzy and busyness that constantly charges this ancient neighbourhood. Here vendors and “snake-oil salesmen” are hawking passersby, offering everything from fruits and vegetables to paraphernalia for birth or death rituals and everything in between. Over yonder, devotees are lined up at the tiny Ganesh temple, pujas in hand, prayers in mind. Further still, young love birds are seeking out quiet corners that might afford them some solitude in the maddening crowd. And all the while, sweetmeats from the traditional Rajkarnikar stores that dot the neighbourhood tempt shoppers and locals alike for a quick, savoury detour. Maru literally has something on offer—both spiritual and material—for everybody.

But more than just being a busy shopping district, Maru is unique because it brings together the two elements that allowed Kathmandu to prosper and grow over the past millennia and more. Lying at the crossroads of two ancient trans-Himalayan trade routes that connected prosperous Tibet to the opulent India in the south, this neighbourhood boasts four famous Sattahs (rest houses in Nepal Bhasa), that made it a hub for travelling merchants. Because the high Himalayan passes were impregnable in winter and the mosquito-ridden sweltering forests in the Tarai were equally impassable in the summers, Kathmandu with its year round amicable weather became the preferred stopover for travellers as they waited for the ideal window to continue their journeys north or south. And when in Kathmandu, Maru was the place to be.

Here, the Kabindrapur Sattah, also colloquially called the Dhansaa:—or treasure room— was used to store valuables the merchants carried with them. Flanking it on either side, the Laxminarayan Sattah and the Si: Lyosattah housed shops that allowed travellers to exchange currency and buy daily essentials for their stay in Kathmandu and future travels. And at the heart of it all, the beloved Kasthamandap (also called the Maru Sattah) towered above fray. The largest and the oldest public rest house in Kathmandu, Kasthamandap is believed to have been built from a single tree in the seventh century. And for 1300 years after, it became the commercial and spiritual wellspring for the city, even lending Kathmandu its very name.

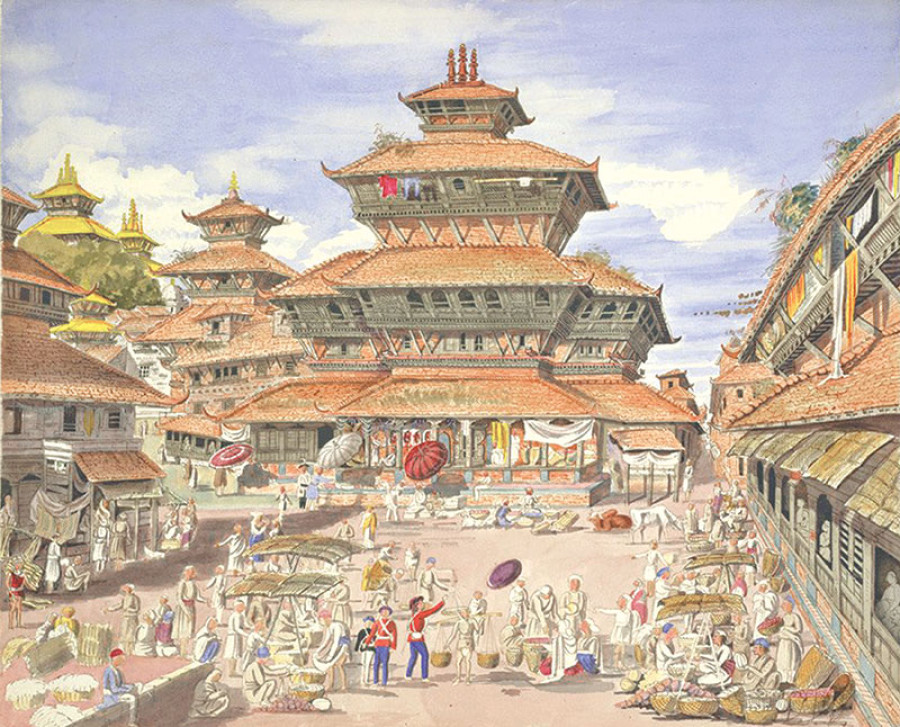

If its status as a favoured transit point for travellers allowed Kathmandu to prosper during the Licchavi and Malla eras, the city’s prosperity was created in the first place by its fertile farmlands that were conducive for a wide variety of crops. And if you were a farmer, Maru is where you’d want to be to sell your fruits of labour. In a 1860s painting by Henry Ambrose Oldfield, a busy farmer’s market under the shadow of the Dhanasaa is depicted as a square bustling with activity. Here an old patron is haggling with a fruit vendor, there a farmer has put aside his Kharpan and is daydreaming on a dabali, and in the background oxen idle in the midday sun. Oldfield may have caught Maru at the tail-end of its most glorious era, but he, in titling the painting “The Marketplace, Kathmandu” succinctly encapsulated the very essence of the neighbourhood.

One-hundred-and-fifty years or so later, today, Maru continues to embody the same spirit it once did, despite the devastating 2015 earthquake bringing down the venerated Kasthamandap. In addition to traditional stores that boast generation over generation of continued operation, newer shops selling clothes, shoes and mobiles have sprung up organically in the neighbourhood today. Emerging rooftop restaurants and mo:mo: shops, and the traditional “Bhatti Galli”—that runs adjacent to Dhanasaa and shoots towards Jhochhen—continue to entice hungry shoppers. What is on offer at this ‘medieval mall’ might slowly be evolving, but the frenzied activity of yore continues to course through Maru’s vein-like gallis that encircle the four rest houses that have seen Lhasa in merchants and Californian hippies alike come and go through the ages.

But what’s perhaps the most warming about Maru is that its vibrancy is derived out of its public spaces and not necessarily its religious cornerstones. Which is why, when locals and heritage activists this week publicly declared their intent to rebuild the Kasthamandap on their own, it felt like the neighbourhood had come a full circle of sorts. Maru was not built out of monarchical grandiosity or business interests, its four public sattahs were built out of a sense of community and service, and these spaces in turn helped shape Maru’s identity. No demi-god casts a watchful gaze over this ancient square; Maru has always been about the people who lived here—either permanently or on sojourns—and their shared interests and compassion. This week’s declaration is testament to the fact that 1300 years after Kasthamandap’s foundations were first laid, Maru continues to bring people together. And if that isn’t worth conserving, nothing is.

- Maharjan is a researcher at Centro Interdisciplinar de História, Culturas e Sociedades, Portugal

9.6°C Kathmandu

9.6°C Kathmandu