Miscellaneous

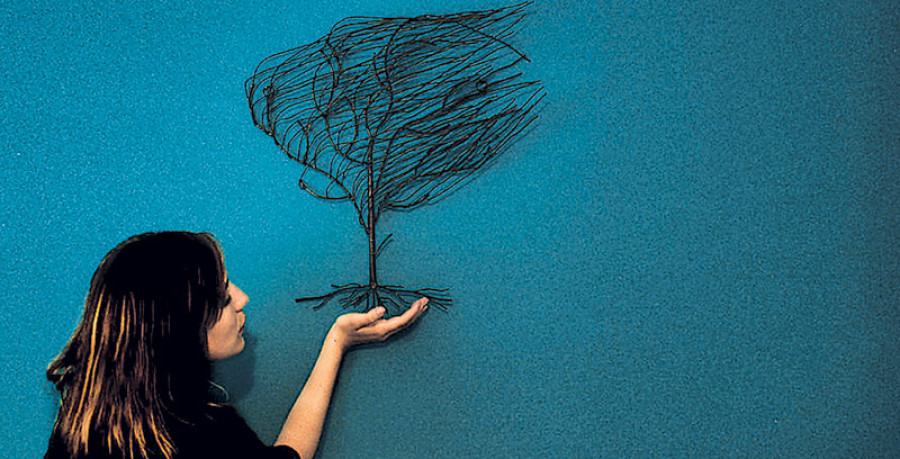

Rootless

When Africans were enslaved by European colonists and taken to the new continent—now known as the Americas—their names were erased and they were given the names of their ‘masters’.

Pooja Pant

When Africans were enslaved by European colonists and taken to the new continent—now known as the Americas—their names were erased and they were given the names of their ‘masters’. The names were, in fact, changed every time a new slave owner bought them—take away their names and you take away their identity; take away their identity and you take away their history. We all know that a people without history are a people without roots. And a people without roots can then be moulded into whatever you want them to be. You, then, control their presents and their futures.

Slavery has been abolished in most countries today, but the erasure of identity and roots continues to take place in another form: through the institution of marriage. Marriage is the foundation of most people’s lives in Nepal but when two people are bound in this ‘holy matrimony’, they enter into an unequal and discriminatory relationship.

In Nepal, the foundation of a family, and that of the society, is built on pillars of discrimination. Here, the root of the problem stems from the notion that a daughter does not belong to her parents. She is to be raised, nurtured and taught all the skills that make her a perfect object to be given away when the right time comes. She is given a new name, and her identity scrubbed off, so further generations cannot remember where she came from.

As most Nepalis, when I got married, I was expected to move into my husband’s parents’ home. As a woman, my role now was to take care of my husband’s parents and to keep his household running.

I was no longer of my family’s clan—a woman joins her husband’s clan and needs to forgo her own. The man’s family is hers now. She has to learn to let go what her mother has taught her, and learn what her mother-in-law will teach her. And if she is a ‘good’ wife—one who is subservient and follows prescribed norms—one day she will be given the prize of becoming a mother-in-law with her own son’s wives to train.

The foundation for inequality in Nepal is in fact laid in the basic concept of marriage. My husband doesn’t need to change his home. I do. A man doesn’t need to bow down to a woman’s parent. She does. A man doesn’t need to cook for her family, sweep her parent’s home, wash clothes, or do the dishes. In Nepal, marriage is not about two people getting together so they can start a new life.

It is about the man bringing free labour to his house. This idea of marriage is so normalised in our society that it is rare to find someone that questions it—no one even pauses to think that maybe there is something inherently wrong with it.

This is taken as casually as we take breathing, something we do instinctively and thoughtlessly. Of course a woman is supposed to move into her husband’s family and learn all the norms, the rules and regulations.

That’s just how it is.

After marriage, a woman is expected to change her last name, which is not much different than changing names to show whose property you are. Then there are the physical signifiers of this ownership. I cannot tell you how many times after I got married that I have been asked by random people: “Tika/ Chura khai ta?” No one asks my husband where the symbols of his marriage are.

My husband is not required to wear any red tika or sindur or glass bangles that signify his marital status. These little symbols imposed on women, on the other hand, are daily reminders that our identities are defined by the men in our lives. By birth a woman belongs to her father’s clan, and then she gets given to her husband’s. We forget who our mothers and grandmothers are. Their blood does not flow in our lineage. Our identities are bound to the men in our lives, but theirs are not bound to ours.

The institution of marriage is solid and unwavering in its treatment of women. My mother was a teenager when she got married to my father. Not yet in high school, she wasn’t consulted or asked for her opinion on the matter. She was still in her teens when she gave birth to me. She was one of the ‘lucky’ ones who got married to a ‘decent home that allowed her’ to continue her education. She ended up getting her Master’s degree and as a youth I remember copying my mother’s notes from her college, as a kind of handwriting practice.

I grew up at a time in Nepal where traditional values often clashed with modern ones. Not a typical girl child, I would be on one of the ends of these clashes. I remember an anger seething inside me for most of my life. I hated what I saw around me.

And while I was coming to terms with my own ideas of womanhood, I could see that patriarchy worked in a way that had managed to turn women against women. In my fight for women’s rights I found myself at odds with more women than I would have liked. Women around me often not only gave in to the patriarchal norms but actively enforced it.

The experience of marrying in Nepal would teach me a valuable socio-political lesson that no book ever taught me.

To be uprooted, your identity wiped out, every freedom taken away from you, you are made to submit. It is a fascistic value system that we collectively have agreed to. But we call it family instead. When the woman moves into the man’s house she is not just moving in; she will now be told what to wear, what to eat, when to leave the house and when to return. She has to submit to her ‘new family’ and forget the old ways. I often wonder if married women in Nepal suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

So when laws are passed that deny citizenship to children based on their mother’s name and property is deemed the inherent right of men, does it come as a surprise to us? The same people who don’t question this patriarchal status quo and who benefit from repressing the other half of this nation are the ones creating and passing these laws. How can we even logically expect our oppressors to make equal and just laws?

We went through a ten-year long uprising in Nepal, which in the end brought us some political changes.

We can now boast that the President, the House Speaker and the Chief Justice are all women. We now have a 33 percent quota system in place. But somehow you can’t help feeling that all these are merely window dressings that try to cover up the rot in the system.

During the war, one-third of the rebel army were women—rural women who left their homes and picked up a gun, because they were sick of it all. They fought believing that only through political changes could women finally free themselves from the shackles of slavery. But without cultural and economic changes, political freedoms seldom matter. After the war, women returned back to the same society they left behind, were made to fit in, and follow, the same rules they tried fighting against.

Without a radical socio-cultural move that has the capability to shatter the myth of a ‘good wife’, and a ‘good woman’, it will take a long time for things to change in Nepal. And the first step towards radicalising our society is to start by radicalising our own families.

Because as Emma Goldman, a feminist and anarchist, once said, “If love does not know how to give and take without restrictions, it is not love, but a transaction that never fails to lay stress on a plus and a minus.”

10.58°C Kathmandu

10.58°C Kathmandu