Miscellaneous

One for the book(store)s

In 2000, I came to Kathmandu; not so much in pursuit of education, as in search of intellectual stimulation.

Ajit Baral

In 2000, I came to Kathmandu; not so much in pursuit of education, as in search of intellectual stimulation. I was beginning to find Pokhara, the city where I was born and brought up, intellectually inert. I did not have a circle of friends with whom I could talk to about books over drinks or a cup of coffee. Nor were there any bookstores where I could buy books or spend time reading them. It’s not that Pokhara didn’t have a bookstore then. It had a few bookstores in Lakeside, but they catered only to the needs of tourists and stocked books that the foreigners wanted to read or had left behind.

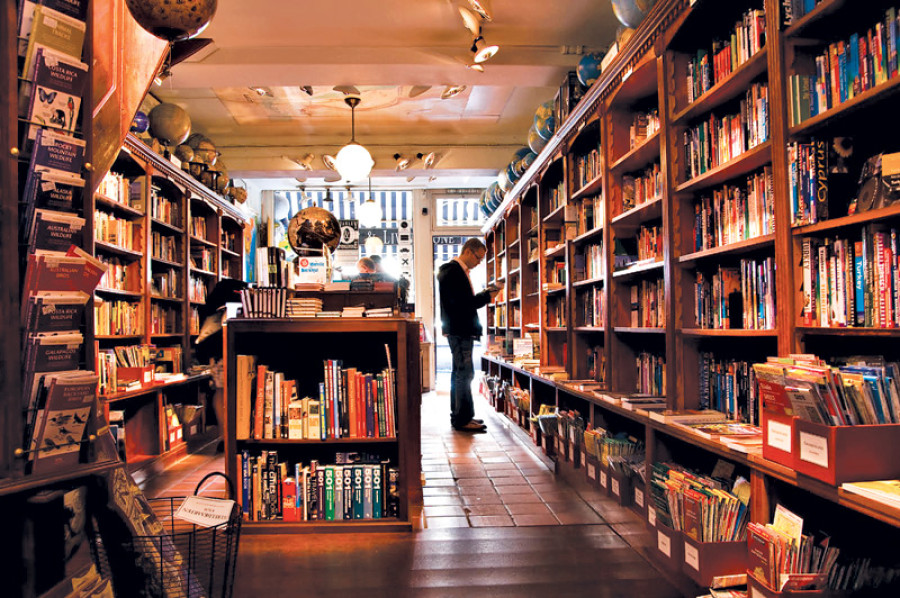

Sixteen years on, I don’t think much has changed in Pokhara, vis-à-vis bookstores. Only one proper bookstore—by proper bookstore, I mean a bookstore that sells only general interest books and not text books—has come up, targeting local readers, while some bookstores in Lakeside have either closed shop or started selling touristy items on the side in a bid to survive. The scene isn’t too different in Kathmandu, either. One tiny bookstore may have sprung up here and another small bookstore shut down there, but I haven’t seen a single good bookstore—with good ambience and ample space, where one would like to spend hours poring over books—turn up since I made Kathmandu home. I find this puzzling—puzzling because I know the readership is growing.

In 2006, I co-founded a publishing company, thinking that publishing would be the best hobby to indulge in for someone who was passionate about books. I said hobby because if I had any thought of turning it into a profession in the future, it was dispelled quite early when I realised that it would be a miracle to sell more than a thousand copies of a book in the country. Sure enough, we only published a thousand copies initially in the first five years. And some of them took ages to sell out while few others went into reprints. But slowly books started to sell in greater numbers and with it our initial print run started to go up gradually—from 1,000 to 35,000—and they have sold quickly despite their large numbers. Of course, we have had the opportunity to publish many of the finest Nepali writers, which has helped the initial print runs, but books brought out by other publishing houses have started to do equally well.

There are a number of reasons for it. First: population growth. In 2000, the population of Nepal was 23 million, now it stands at 28 million. This growth is giving rise to new readers. Second: rising literacy. In 2000, the literacy rate was under 50 percent; while in 2016, it is 66 percent. More importantly, the literacy rate of the youth, which comprises the bulk of the reading populace, is 90 percent. The more literate the people are, the more likely they are to read. Third: an increase in per capita income. In 2000, Nepalis’ per capita income was $259; now, it is nearly $700. We can assume that people now have more surplus money than in 2000 to spend on books, which are basically a non-essential item. Fourth: media boom. In recent years, the number of newspapers and magazines, television channels, FM stations, and online news portals has grown steeply, creating multiple avenues for the promotion of books. And fifth: the rapid expansion of social media, which have been acting like, among others, online book clubs and book review pages, giving exposure to books. The most fascinating factor behind this, though, seems to be psychological—this thirst to know and learn, to seek out books that your social circle is talking about, to idolise authors and respect the value of words.

That begs the question, if the readership is expanding, book sales are growing and publishing houses are proliferating, why aren’t there more new bookstores?

I asked this question to a few booksellers. Madhav Lal Maharjan, the owner of the Mandala Book Point, which is a hub of Nepali academics, says, “That is maybe because shops that previously dealt exclusively in text books and stationery have now doubled up as an outlet for general interest books, seeing them doing well.” No wonder, we see popular fiction and memoirs of public personalities displayed on show cases or hanging from ropes in stationery shops around schools and colleges.

Govinda Shrestha, owner of the oldest existing bookshop, Ratna Pustak Bhandar, says that we are not seeing newer bookstores coming up for investment and overheads reasons. “The initial investment,” he says, “is huge. The rent, if you want to run a bookstore in a centrally located place, is very high but the sales volume is not large enough to cover overhead expenses. Why would anyone invest in a business that is difficult to sustain?”

Raman Raut, the manager at Educational Book House, which is at the heart of Kathmandu, also doesn’t see much incentive in opening a bookstore. He says, “The profit margin is not high enough and the competition is cut-throat with booksellers giving discounts up to 25 percent, and what little money you make goes into retaining stocks both old and new.”

And with e-books and online retailers emerging on the scene, these booksellers don’t see any future for the usual brick and mortar bookstores. But that, as Maharjan says, doesn’t mean the end of books. The good old days of bookstores, if there was one, may be over, but people will keep reading in increasing numbers until the readership flattens out.

9.6°C Kathmandu

9.6°C Kathmandu