Miscellaneous

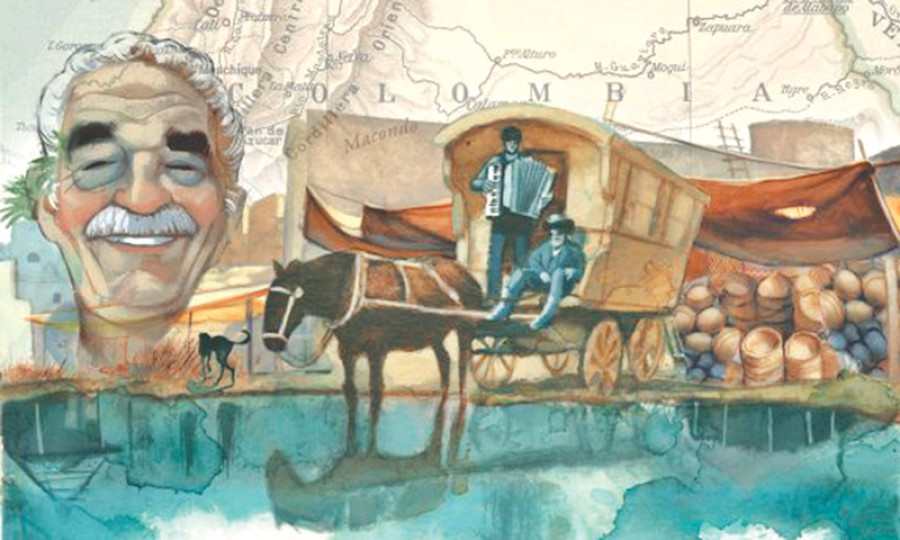

Revisiting Macondo

For decades readers and scholars around the world have interpreted Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude as a heroic story of struggle against colonisers by native population that ultimately capitulated to outsiders’ demands and became victims of its rapacious appetite.

Abhinawa Devkota

For decades readers and scholars around the world have interpreted Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude as a heroic story of struggle against colonisers by native population that ultimately capitulated to outsiders’ demands and became victims of its rapacious appetite. This widely acclaimed novel is the story of Macondo, a city in the backwaters of South America, a saga of the village from its birth to the moment it is about to be “wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men,” narrated through the lives of generations of a family living there.

But while this kind of black-and-white reading, which places victims and victimisers on the opposite sides of the morality scale, does hold true in many instances, it does not reveal the full complexity of Macondo, a place rich in paradoxes with an equally rich variety of characters.

Here is how the story begins: Once upon a time there was a place,

remote and desolate, inhabited by a handful of people and strange creatures. Cut off from the rest of the world by high mountains on the one side and marshes on the other, it saw no outsider except a bunch of gypsies who came there once a year. (Macondo, by the way, seems to share similarities with Nepal on more than one level. Its geographical isolation and the hardscrabble life the people live largely resemble ours. So do the disorder and chaos that engulfs the place later in the novel.)

This could have been a fairytale-like beginning of a happy story that ends with an ode to innocence and pastoral beauty had it not been for the problems that come to the fore now. Not that the residents of this place were paragons of virtues to begin with, but the community slips into a downward spiral soon enough. With the village establishing contact with the world outside, peace quickly gives way to war. Terror reigns. The village teeters on the brink of destruction for a while before plummeting into the horrors of civil war, which is led by none other than a member of the Buendia family.

But instead of lasting peace, it leads to more chaos, which culminates, after a successive change in governments followed by a mass slaughter, into its becoming part of a colonising country. To quote the idiom widely popularised by Latin American writers, Macondo becomes a banana republic.

This is often taken by critics as a hallmark of colonial maneuver: the way countries in Europe extended their reach into places around the world by the use of brute force that resulted in death of countless people in search of resources with economic potential. But following this logic often means negating the presence of native characters involved in the process. Macondo’s misfortune cannot solely be blamed on its discovery by the world outside. Its fall begins with the obsession the founding father of the city, Jose Arcadio Buendia, for wealth and violence, so vividly portrayed in his attempt to turn base metals into gold using secret alchemy and lenses powerful enough to incinerate enemies.

As the novel progresses, the trait spreads into other members of his family and becomes more pronounced. Friendship gives way to hatred; honesty to corruption; restraint to excess. He fathers a blood-thirsty rebel leader and a repressive tyrant. What seemed to be a hilarious attempt of seemingly scientific inquiry take a morbid form a few decades down the line as alchemy is replaced by loot and incinerating lenses by guns.

One night, before the founding of the village, Buendía dreams of a city of mirrors that reflects the world within and around it. The world within is but complex, and often barbaric, human nature bent on annihilation. The destruction of Macondo has to do as much with greedy, rapacious colonising forces and changing times as with equally greedy and bloodthirsty natives. Márquez’s opus is a fine study not just of magical realism and post-colonial literature but of human nature. It’s high time we modified our view about the masterpiece.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu