Miscellaneous

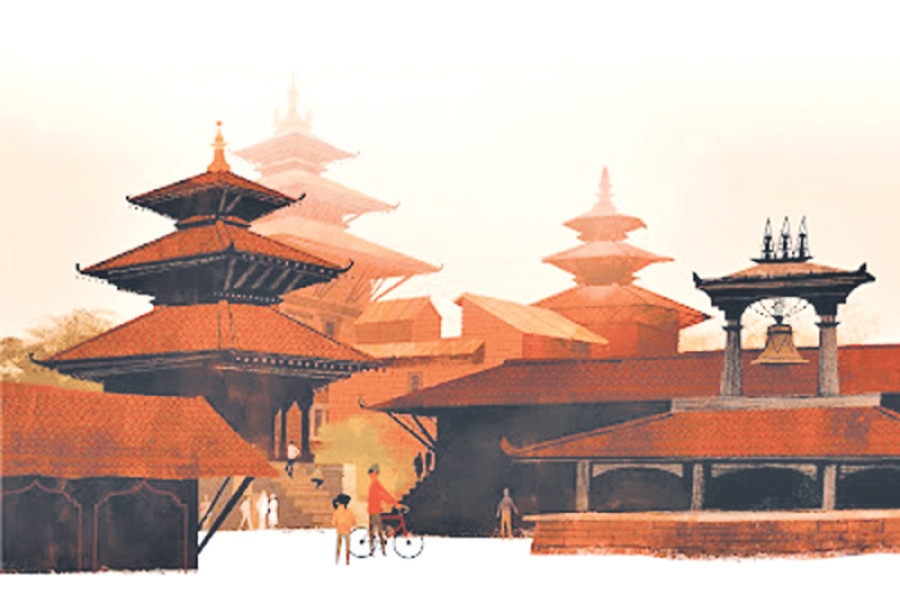

Brave new Nepal

In the early 17th century Spanish novel Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes narrates the adventures of a knight errant trying to set the clock back to the good ol’ days when warriors ruled the roost.

Abhinawa Devkota

In the early 17th century Spanish novel Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes narrates the adventures of a knight errant trying to set the clock back to the good ol’ days when warriors ruled the roost.

An avid reader of chivalric romance, he soon loses his sanity and decides to set out to punish wrongdoings and bring justice to the world as a knight might have done in the past. He recruits a simple farmer, Sancho Panza, as his squire, comes to regard a neighbouring farm girl as his ladylove, calls an inn a castle and fights windmills thinking they are giants.

The mental affliction that Quixote suffers from, which leads to the denial of reality and, according to the French critic and literary theorist Michael Foucault, is a result of the dissonance between words and things (words here stand for the chivalric ideals in Quixote’s head while things mean the world outside), does not just provide for moments of comic relief but also intimates us with the role imagination plays in navigating and interpreting the world around us.

Back in the day the novel was written, imagination as a means of interpreting one’s surrounding was a revolutionary concept. But what was so radical and ground-breaking back then has now become vital in navigating the chaos of the modern world, especially in a country like Nepal with its mind-boggling heterogeneity, where fractured identities and multiple ideologies are all competing for expression.

Gerard Toffin’s latest work, Imagination and Realities: Nepal Between Past and Present, attempts to synthesise both the imaginative aspect and ground reality of the country into a coherent whole to provide an in-depth, well-rounded picture of the country without sacrificing on the diverse, multi-cultural tapestry that has become an integral part of our common identity.

It is as if a freakish geographical accident made diversity part of our collective heirloom. The collision of the Indian Plate with its Eurasian counterpart along the present day Nepal-India border not only created mighty mountains, rolling hills and plunging rivers, but also divided the country between two geographical ensembles (to use Toffin’s words). The first ensemble consigns us to the Hindu Kush belt, which comprises eight countries including China and Burma, while the second one makes us an integral part of South Asia and aligns us with countries as far flung as the Maldives and Sri Lanka.

If the subduction gave us the Himalayas (and earthquakes), it also resulted in economic woes. Geographically cut off from the rest of the world until recently, having no substantial resource to speak of and with inhospitable terrain and low agricultural output, poverty is the inheritance that most Nepalis have in common with each other.

This everyday reality has further been exacerbated by the fictive and the imaginary. With Hinduism as the dominant religion, ideas of social hierarchy, purity, exclusion and repression run deep, further marginalising and impoverishing those at the bottom. Worse still, these ideas are not just limited to the Hindus but are, in varying intensity, present in different ethnic groups.

Attempts to redress this rampant socio-economic inequality have been mostly ineffective at best and gruesome and violent at worst. The quota system exists, and benefits few, but at the cost of reinforcing the differences; and legal remedies against discriminations are available but few have access to it. Even radical, Western utopian ideas like Communism have proved to be largely unsuccessful in addressing the malaise

The Maoist revolution, with its promise of replacing the rule of the elites and comprador-bourgeoisie with that of the working class, did garner a lot of sympathy among peasants and lower-class people, but ended up being abused by its self-serving leaders. Thousands of rural folks, with a long history of oppression and impoverishment behind them, raised arms against the state only to find later that they had been duped.

But the picture of contemporary Nepal is far more complex that one painted by the narratives of Hindu domination, economic inequality and caste system. Cultural patterns are shifting with changing times. Egalitarian ideas and liberal worldviews are replacing old ideas in some circles. It can be found in the increasing popularity of intercaste marriages, in women working in fields traditionally dominated by men, in the more relaxed cultural and religious outlook, in migrant workers who cross the ‘blackwaters’ for employment (sans the elaborate rituals their ancestors had to participate in order to cleanse themselves of the sin on returning back).

If there is excitement and jubilation about the future on the one hand, there is also a palpable sense of fear on the other. One thing that has been hindering us from fully modernising ourselves is our own nostalgia of the past. Like the protagonist Palpasa from Narayan Wagle’s debut novel, even the young, educated and worldly among us seem to have a deep, ineffable affection for the past, however discriminatory and outdated it might be. Like her, most of us have “one foot in the modern world and one in the traditional one”. Add to this the emergence and spread of parochial, nativist and chivalric ideas in the recent past and it is not difficult to realise how easily can the achievements of the past be undone.

Written in a simple and elegant language, with deep scholarship and a penetrating eye for detail, Toffin’s latest book takes a nuanced look on contemporary Nepal and those who live here. But it hesitates from answering if ideologies as vague and universal as pluralism and egalitarianism worldview can be the sole bearer of our national identity or if we also need to complement them with something else. Something that draws deep on our common heritage and centuries of interaction, something that we can anchor our identity on. Else, unmoored from the past and baffled by the present, we might start acting like Cervantes’ hero.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)