Miscellaneous

The hero in all of us

Whether in villages where “to stay is to die” or on the forty-fifth floor of the Canada Tower, most of us live our own lives in quiet desperation; hoping for change but never quite acting on it, forever lingering at the threshold of something greater.

Sanjit Bhakta Pradhananga

Life is seldom Odyssean. Buckling under the weight of unrequited dreams and the instinctive need to fit into the larger picture, we straggle on—pillar to post—never quite whole. Whether in villages where “to stay is to die” or on the forty-fifth floor of the Canada Tower, most of us live our own lives in quiet desperation; hoping for change but never quite acting on it, forever lingering at the threshold of something greater.

It is here—at the threshold—that we find the four “heroes” of Manjushree Thapa’s All of Us in Our Own Lives. Ava Berriden, a Toronto-based corporate lawyer who was adopted as a child from an orphanage in Kathmandu; Indira Sharma, a relentlessly ambitious gender expert in a country where “Always, men are there”; Sapana, a sheltered village girl who is fast losing the support systems that once cushioned her from the world; and her half-brother Gyanu, torn between a new life he has found in the unforgiving desert and the old one he left behind, are all at the cusp of being forced to venture into the great unknown, inviting the reader to join their journeys—literal and those of the mind.

Thapa’s latest novel is a recasting of the Campbellian monomyth with characters that are, by and large, leading undistinguished lives. These are not Homeric adventurers or the mother of dragons, but rather the frustrated mothers of “useless” video game-obsessed sons, the dutiful sisters of overbearing brothers and the caged wives of indifferent lovers. Which is why All of Us in Our Own Lives is immediately relatable and arresting—the “heroes” could be anyone of us in our own banal lives. For after all, aren’t we all on epic personal inner journeys?

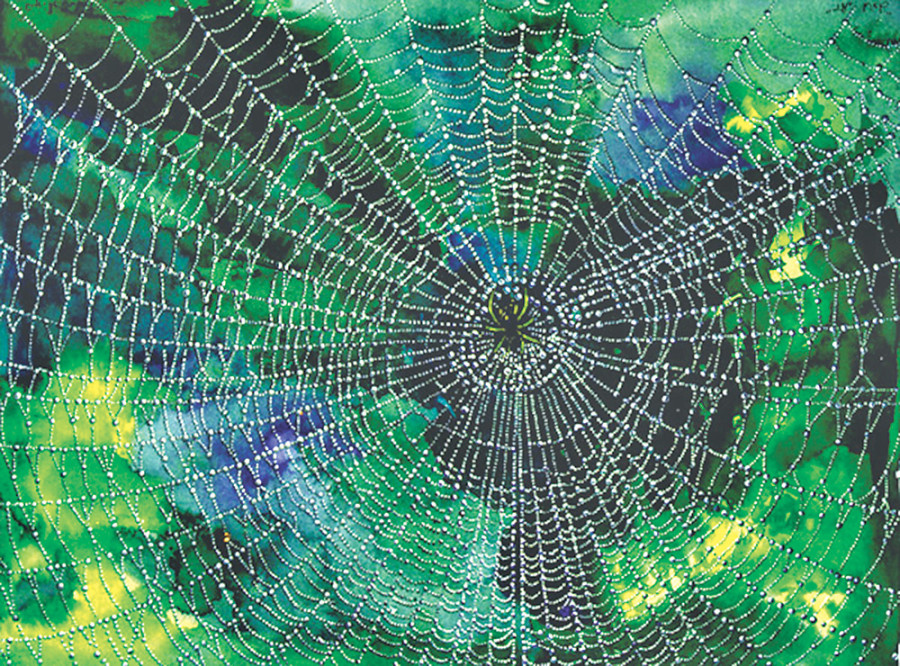

It is these journeys that drive us out of our comfort zones as we quest for a “chance to be fully alive” and bring us in touch with strangers who go on to become guides and gurus in our transformations. The novel, then, is also an exploration of the notion of interdependence, or as Thapa puts it, the fact that “Maybe there’s no such thing as ‘my life’ or ‘your life’, may be everyone’s life is part of a whole...the actions of one person shape the lives of others...like some kind of design, some kind of order.”

But then again, this is a Manjushree Thapa book—incomplete without her incisive commentary on the society at large. The book, set in the convoluted world of foreign aid, unabashedly calls out the “aid industry,” which as one character decries, “is a collusion between the international and national elite”; an “industry” that speaks its own jargon-laden lingua franca and thrives in a exclusive bubble “designed to keep Nepal out.” An “industry” haggling between the use of the terms “poor and marginalised” over “socially excluded” while despite the phraseology the Fucches of the country are being compelled to take jobs in the desert—where overworked and despairing they tether at the brink of suicide.

The book also lays bare the misogynistic and patriarchal society where all women are survivors, the impossible restrictions of which trap not only village girls like Sapana, Chandra and Namrata but also the Indira Sharmas who lead bipolar lives of industry leaders and resentful daughter-in-laws at the same time. Even Ava, silently ostracised by her landlord and gatekeeper’s quiet judgements, is never quite free of the expectations Nepali women are forced to honour, even if they are outsiders. It is in this backdrop, in a land “that makes its women cry”, that the narrative truly shines through; and Indira Sharma is, understandably, the book’s most layered and intriguing character. The inherent contradiction of leading the good fight for women empowerment while under-compensating her own household help (or “slave” as one character puts it), speaks to the larger society’s tacit compliance with inequality—whether based off gender, ethnicity or poverty. The embattled co-director of WDS-Nepal, Sharma, is also fascinating because hers is a voice seldom heard in mainstream discourse. The “first-generation” working women who pioneered the diversification of the Nepali workforce but always remained confined by familial and societal glass ceilings may seem a dime-a-dozen, but how often do we hear them speak, let alone read, their inner-most thoughts—their unfulfilled dreams, their unrequited longing for “choclatey” strangers? Indira’s voice is refreshing and invites the reader to examine not only the society’s double-standards but latent biases of their own.

And that is where the novel’s greatest strengths, and only weakness, lies: All characters go through transformations that bring them a full predictable circle, emerging on the other side wiser, older and braver, if still scarred. If the first half of the novel is an engrossing build-up to when the lives of the four protagonists converge, the pace tapers off drastically in the second half. So much so, the mentions of the promulgation of the new constitution and the earthquake read, in places, as expendable tag-ons—an afterthought. If the opening scenes have the reader empathetically cheering the “heroes”, the character arcs, when they come full circle, can be off putting, even if the outcomes were exactly what you were rooting for in the first place. As Indira Sharma would put it, “Nepal is Nepal,” a “strange, difficult, complicated country”; here all happy endings ought to be met with scepticism, even those in well-crafted novels. Life, after all, is seldom so Oddysean.

All in all, Manjushree Thapa’s All of Us in Our Own Lives is an engrossing read that can be wolfed down in one honest sitting. Thapa’s natural wit shines through the heavy motifs, particularly via characters like the CK Lal-tinted Herman Banke, Mrs Thapa and Harihar the gatekeeper, which ensure the pages keep turning. Not that there aren’t other books rooted in Nepal, but ones that steer clear from “Nepalsplaining and Mansplaning” are a rare breed. Which is why, fresh, introspective and incisive, All of Us in Our Own Lives is yet another testament to why the Manjushree Thapa is one of the very best Nepali writers writing in English.

11.12°C Kathmandu

11.12°C Kathmandu