Interviews

Constitution review is certain, amendment only if needed

If the amendment process begins, it will be limited to the extent of ensuring political stability. We won’t touch other aspects of the constitution.

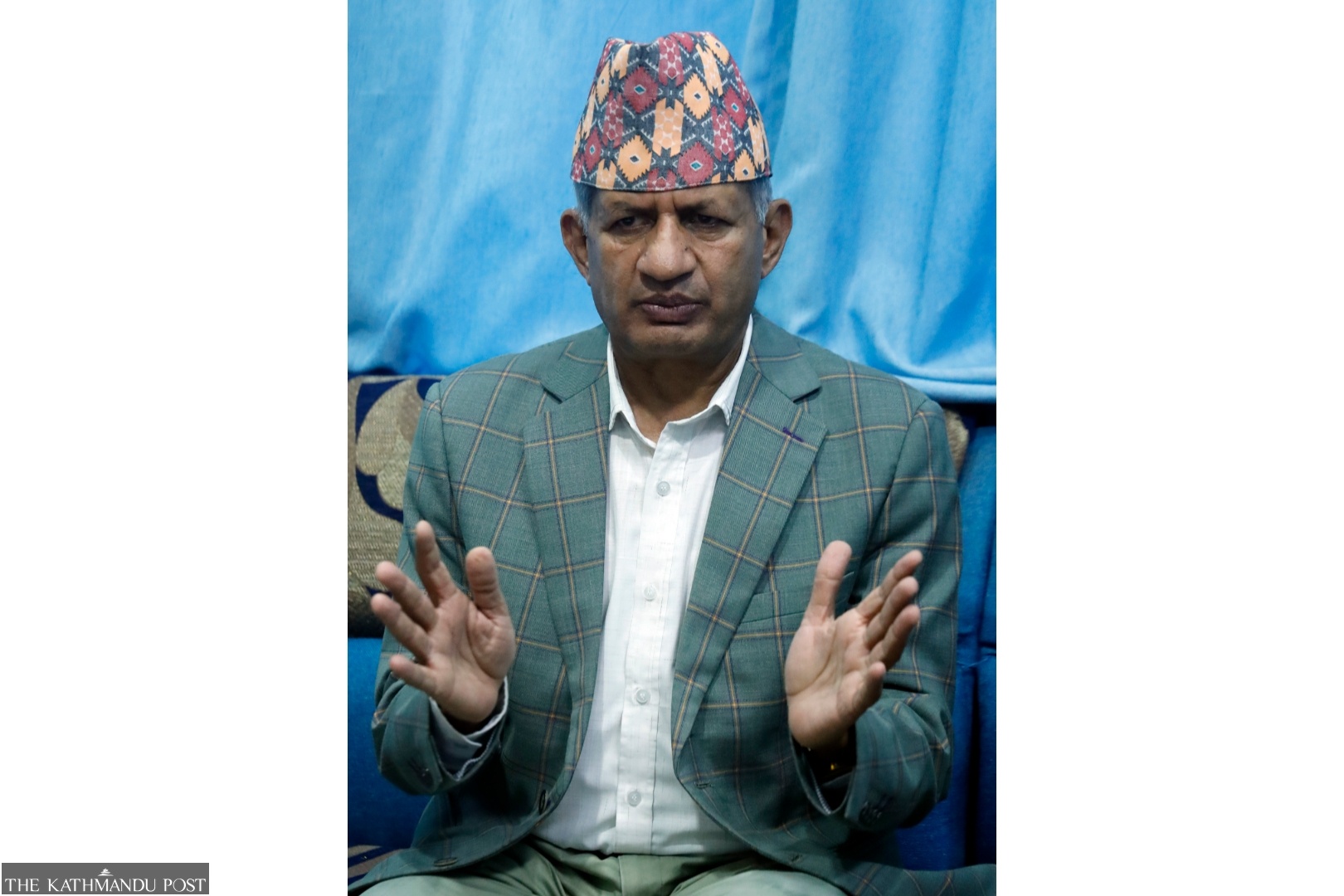

Thira Lal Bhusal

The Nepali Congress and the CPN-UML last week reached an agreement to form a coalition government under the leadership of UML chair KP Sharma Oli. As a part of the package, they also aim to make certain changes to the constitution. The Post’s Thira Lal Bhusal asked Pradeep Gyawali, deputy general secretary of UML, the reasons behind the coming together of the two largest parties, how they plan to run the government and to review and amend the constitution.

Many are seeing the Congress-UML alliance as something unusual. What factors brought the two largest parties together even as there is no crisis-like situation or a special task such as constitution writing?

Definitely, in normal parliamentary practice, the two largest parties don’t forge an alliance to run a government. The party that gets the biggest mandate leads the government, and the other big party remains in the opposition to make the ruling force accountable. In Nepal, the country’s two major forces, the Congress and the UML, have also joined hands in certain junctures for certain purposes. They worked together to make the constitution in 1990, to conduct general elections in 1999, to complete transition after the 2006 people’s movement and to bring out the constitution in 2015.

We felt a need for a similar collaboration this time around. After the November 2022 elections, we saw three alliances in our parliament. At first, Maoist Centre chair Pushpa Kamal Dahal became prime minister with our support, but he failed to abide by the agreement sincerely. He changed the coalition within a month. The subsequent alliance between the Congress and the Maoist Centre lasted for a year. He again sought the UML’s support. Within four months of the March 4 deal with the UML, he started yet another gameplan to join hands with the Congress under the pretext of forming a national consensus government. It was quite unusual for the prime minister himself to instigate instability in the government.

He publicly boasted that he had a ‘magical number’ [32 seats in the House of Representatives]. He thought that he could employ the tactic of ‘use and throw’ with the two largest parties and rule the country for the full term. He was completely indifferent to people’s plight, the country’s pressing issues and service delivery. This was the height of irresponsibility. So, the UML and Congress leaders concluded that the time had come to intervene to ensure political stability and service delivery and make sure public frustration doesn’t get out of hand.

Did external factors play a role? Recent statements by UML leaders suggest that the party has taken it seriously.

When national forces are weak, the neighbouring countries and international forces become more cautious, even more so given Nepal’s geo-political situation. Some of their concerns are valid. They fear political instability in Nepal may have an adverse impact on their genuine issues. We have to take this naturally. Second, it is no secret that we have a long legacy of facing external interference. Sometimes such interventions are carried out covertly and sometimes overtly. Therefore, national forces should be strong. Some political parties and leaders have a tendency of seeking external forces’ support to fulfil their vested interests. In return, they serve the external forces’ undue interests. Formation of a government is a purely domestic affair, but in our case sometimes it also becomes an issue of geopolitical interest.

It is said that the UML was spooked when it learned that Prime Minister Dahal had reportedly approached the Congress for a new alliance. This reportedly happened after Dahal returned from New Delhi following Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s swearing-in.

We were taken by surprise when the Congress leaders told us that the prime minister had reached out to them with a proposal to form a national consensus government. We were informed about the development from the leaders of the main opposition party. When we reached the March 4 deal with the prime minister, we thought he came to us with a commitment to course correction. Based on that, we supported him almost unconditionally. We didn’t bargain while sharing ministerial portfolios and didn’t talk about the prime minister’s term. We had even thought of allowing Dahal to run the government for the full term if the government functioned well and people were satisfied. We hadn’t even imagined that we would have to think about changing the coalition within four months.

We definitely had certain grievances such as a lack of consultation with our party and our lawmakers while preparing the government’s policies and programmes and while allocating budget. Our party chair brought up this issue with the prime minister. But our concerns weren’t addressed. They had already started to ignore us. There were several issues with the prime minister, but we were committed to the partnership. But they had already gone too far. Fortunately, the Congress leaders didn’t accept the offer and instead raised critical questions about the rationale behind the proposal. Basically, the Congress didn’t trust Prachanda ji [Dahal] and came to us. It concluded that Dahal didn’t come with the intent of solving the country’s problems but to manoeuvre between the Congress and the UML.

Besides jointly running the government, constitution amendment is another major aspect of the latest Congress-UML deal. What are the provisions the parties want to change?

There are four major objectives of this agreement. Safeguarding national interest; strengthening economy; improving governance and service delivery; and ensuring political stability. A debate has started that some constitutional provisions are not helping maintain political stability. What we have said is that it’s been almost a decade since the promulgation of this constitution. Some of its provisions are yet to be implemented. On the other hand, provincial governments complain that they have not been able to work in a full-fledged way because the federal government has still not made some laws they need. So, first, we will undertake a comprehensive review on the progress in the course of implementing the constitution and the challenges we faced in the past decade, among other things. While doing so, we will find out if there are provisions that have posed challenges in maintaining political stability and running a stable government and suggest amendments accordingly.

So, it’s not only about the amendment but also about review, assessment and recommendation for amendment, if there is a need. Even if the amendment process begins, it will be limited to ensuring political stability and won’t touch other aspects of the statute. There is no need to over-react. For instance, some Maoist leaders are trying to make it a political issue by describing it as a regressive move. That is wrong.

So as per the two-party deal, the statute will be reviewed but not necessarily amended?

Yes, whether to go for amendments will depend on the findings of the review. No constitution in the world is perfect. Its success largely depends on the practitioners. So, first we have to differentiate between the role of the constitution and the practitioners. It is true that our society is divided over certain provisions of our constitution. All these issues will be considered, but the fundamental features of the constitution such as democracy, inclusion and federalism won’t be altered. Our priority would be to only remove hindrances in making the system more functional, people-oriented and productive.

Of late, people are debating the electoral system, provincial structure and secularism. Will these issues also be dealt with?

Federalism is a new system for us. In fact, it is still an in-the-making process in Nepal. We have to note some timelines while analysing the performance of provinces. After the provincial and federal elections in 2017, the first provincial governments were formed in 2018, and they worked for around three years in a stable way. With small cabinets, they worked genuinely to strengthen the provincial system. At the time, most provincial cabinets had around six to seven ministers. They weren’t severely criticised at the time. The wrong trends in the provinces started with the division of the then Nepal Communist Party and the fall of the NCP-led governments at the centre as well as provinces. We saw the trend of horse-trading in provinces. Small parties made unjustified bargaining for ministerial portfolios, chief ministers started splitting ministries and increasing the number of ministers in their cabinets. Also, the November 2022 polls again gave a fragmented verdict, further augmenting the instability and anomalies at the provincial level. So, the problem is the way we are handling things more than the provincial structures. The time isn’t ripe to seek an alternative to the provinces.

As far as the electoral model is concerned, we included proportional electoral (PR) system after long debates and discussions. Based on three general elections held after 1990, a conclusion was drawn that the first-past-the-post (FPTP) model couldn’t properly represent the historically under-represented sections. The premise is still valid. Based on the achievements, we may exclude certain communities from the list. But that time hasn’t come. Two questions raised over the use of PR are valid. Is the system really doing justice to the strata and class of the society for which it was introduced? This is the question not about the PR system but the leaders who use it. Similarly, some questions: Is proportional representation required in executive as well because representation is basically vital for policy making? The forms and modalities of the PR system might be discussed, but no one has even thought of removing the inclusive system.

Similar is the case with secularism. The spirit is to make the state patron of all religions in the country. However, some sections of society have often tried to misuse and misinterpret the new constitutional provision. They try to interpret secularism as openly allowing rampant religious conversion, and some have made it an excuse to attack the age-old Sanatan faith. For instance, if the President or prime minister visits Lumbini, gurudwara or a shrine of any other faith on certain occasions, that is taken positively, but when they visit Pashupatinath Temple, a section of people raise questions. These activities have made some people think that these attacks on our Sanatan faith are taking place because of the secular system. There is no problem in the constitutional provision because the statute added an explanatory note that states, “‘secular’ means religious, cultural freedoms, including protection of religion and culture handed down from time immemorial.” But some extremist activities have given wrong impressions.

Some experts believe the problem of fragmented mandate can be addressed by increasing the threshold required for a political party to be eligible to get PR seats, which can be done by amending laws. Will the Congress-UML alliance opt for this?

Yes, this is one feasible option. I am in favour of this. As per the existing provision, a political party can secure seats under the PR category by securing 3 percent votes in the federal parliament and 1.5 percent votes in provincial assemblies. If a political organisation doesn’t even represent 5 or 7 or 10 percent of the population, what can they contribute to the country? You do politics to represent a sizable population and get a public mandate. Otherwise, the presence of such groups would only promote unreasonable bargaining and instigate instability in governments. This can be one of the agenda of the discussion between the two parties.

This time, leaders have made it transparent that chiefs of the two parties will lead the government on a rotational basis. But why have other details of the agreement not been made public?

There hasn’t been topic-wise discussions on specific provisions. The broader understanding is to review and assess the implementation aspect of the constitution and move ahead based on the findings of the assessment. We have also made it clear that such an act will be guided only by the objective of ensuring political stability and we will not go beyond that.

Who will undertake this type of constitution review?

We haven’t worked on it in detail. We haven’t reached any understanding. Naturally, inputs will be taken from the constitution makers, experts on constitutional law and politicians involved in this field. But no decision has been made on its nitty-gritty.

The Rastriya Prajatantra Party that wants to revive the Hindu kingdom was the first party to welcome the Congress-UML deal while the Maoist Centre has accused Congress and UML of making a regressive move. So don’t you think this affair is tricky?

I don’t think the political parties will touch the issues that the RPP talks about, such as reinstatement of Hindu kingdom and dissolution of federalism. No one is thinking about that. Also, the questions raised by the Maoist leaders have no meaning. They are only trying to make a political agenda.

It also seems that the Congress and the UML floated this idea of reviewing the constitution to make a case for the two largest parties to form the government.

That’s not true. This question undermines the spirit of this agreement. If this system fails, people will raise questions mainly to the leaders of the Congress and the UML, not Prachanda. It’s not only about running the government. We were already in the government and it isn’t a big deal for the Congress to return to power. If democracy fails, the democratic forces will lose the most. So we are genuinely working on this.

The Congress and the UML are historical rival forces in Nepali politics. How can the two work together in government?

It is true that the Congress and the UML are the two major competitors of this country. But we have some converging factors. First, we both believe in a broader democratic framework. Sometimes, the Congress may give more emphasis on liberal values while we may push for more socialism-oriented programmes. But the common ground is democratic values. We also have the experience of successfully carrying out certain tasks jointly. We may have some friction but we also have experience of managing bitter intra-party fighting as well as inter-party rivalry.

How will the ministerial portfolios be shared in the new coalition?

We haven’t reached any agreement in detail. As we aim to make this a ‘national consensus government’ we are in favour of accommodating other parties. So it will depend on the number of parties that join the Cabinet. Our only concern is that ministerial allocations should be done in a way that doesn’t weaken the prime minister in order to ensure that the head of the government can deliver.

How can a government without the Maoist Centre and some other parties be called a consensus government?

We have to wait for that. Leaders of political parties that fiercely criticise the government also join the Cabinet under one or other pretext. Some political parties seemingly cannot exist without being in the government.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu

.jpg&w=200&height=120)