Health

Nepal postpones malaria elimination deadline to 2030

Authorities have missed the target multiple times. In 2024, the number of malaria infections was 1,043, nearly double that of 2023.

Arjun Poudel

Nepal has once again missed its malaria elimination deadline, which has now been postponed to 2030.

But as new cases of both indigenous and imported malaria continue to rise each year, and with both existing and emerging challenges, experts are sceptical about the country’s ability to eliminate the disease even within the next five years.

“We could not achieve the goals by the set deadline,” said Dr Gokarna Dahal, chief of the Vector Control Section at the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division. “Multiple factors hindered the progress.”

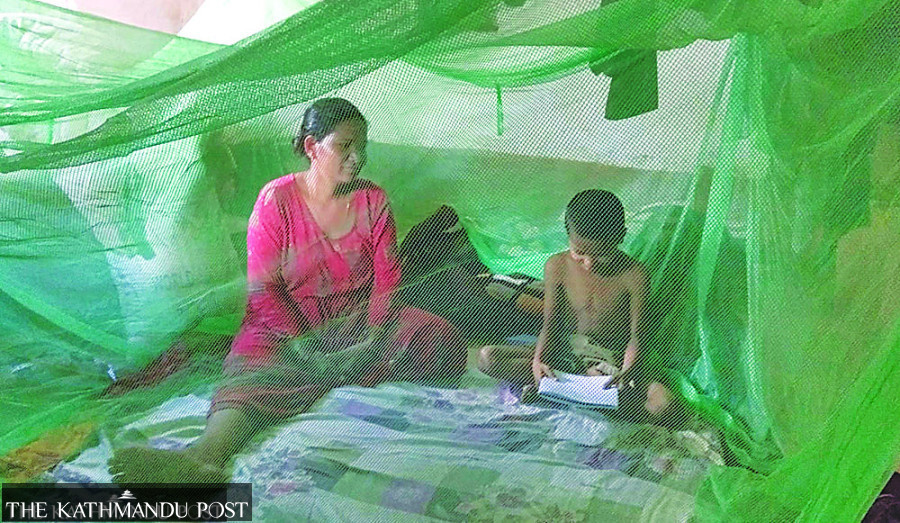

Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites. Infected female Anopheles mosquitoes carry these deadly parasites, according to the World Health Organisation.

Indigenous malaria cases are locally transmitted; infected persons do not have a history of travel to malaria-affected countries. Meanwhile imported cases are those who had a history of travelling in the disease-hit areas or countries.

Nepal has missed its malaria elimination target multiple times in the past—2026, 2023, and 2020.

The country had committed to achieving ‘malaria-free’ status in 2026. For that, the country had to bring down indigenous cases or local transmission of the disease to zero, achieve zero deaths from 2023, and sustain zero cases for three consecutive years, according to the World Health Organisation.

However, infections of both indigenous and imported malaria cases rose in 2023 and 2024.

According to data provided by the division, 1,043 new malaria cases—including 1,006 imported and 37 indigenous—were reported in 2024, up from 528 cases, including 23 indigenous, in 2023.

Public health experts and entomologists said that they are skeptical about the country’s ability to eliminate the disease even within the next five years, as the country is witnessing all existing and emerging new challenges. Open borders, global movements and mosquitoes moving to higher altitudes due to climate change pose challenges to the elimination goal, they said.

“It is not easy to eliminate the deadly disease without curbing imported cases,” said Professor Murari Das, an entomologist at BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences. “The problem is not only that our migrant people get infected in various cities of India but also peacekeepers in various African nations, who bring the disease in the country, which later becomes indigenous due to transmission from local vectors.”

Of the total imported cases, over 80 percent have come from India. Due to proximity, and an open and porous border between Nepal and India and unregulated travel of people of both countries, it is impossible to eliminate malaria here in Nepal, until the disease gets eliminated in India, said experts.

Some cases were imported from African countries. Nepali security personnel serving in UN peacekeeping missions in conflict-hit African countries have also tested positive for malaria.

Officials at the health ministry said that until recent years, Plasmodium Vivax, a protozoan parasite, was responsible for most of the malaria cases in the country, which is relatively less severe.

However, cases of Plasmodium falciparum, which most often causes severe and life-threatening malaria, have been rising. The parasite is common in many countries in Africa and the Sahara desert.

Several other factors, including cuts in the health budget from government and aid agencies, and shifts in vectors transmitting malaria to the hills and mountains due to global warming also pose serious challenges to meeting the elimination target. Apart from this, most health facilities across the country lack entomologists, who play a crucial role in surveillance.

Unlike in the past, when malaria was concentrated in Tarai districts, a large number of cases are now being reported from hill and mountain districts such as Mugu, Bajura, and Humla, which were considered non-endemic in the past.

Apart from this, isolated indigenous cases of malaria have emerged as a major challenge to eliminating the disease from the country. Officials concede single indigenous cases of infection have been reported from several places, and health authorities concerned struggle to trace the source of infection.

Health officials, nevertheless, said that measures have been taken accordingly to meet the target by 2030.

“National strategic plan for malaria elimination has been approved, and measures are being taken to achieve the goals,” said Dahal. “We have been working to make the surveillance system robust; lessons from our past experiences will be learned, and measures will be taken accordingly.”

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu