Health

Current efforts to slow the virus not working, time to start antibody tests, doctors say

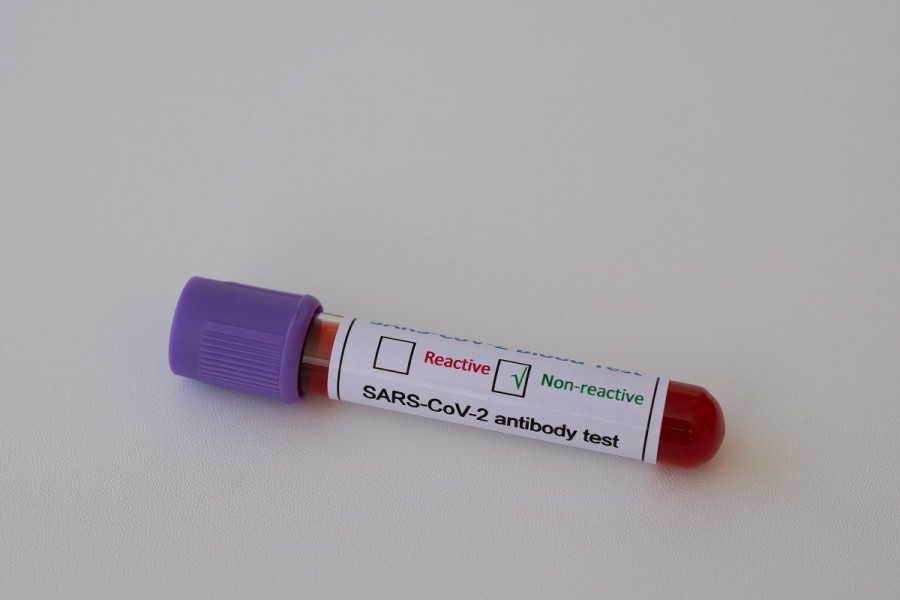

The mass testing, or seroprevalence survey, can provide estimation on the percentage of people in a population with antibodies against SARS-Cov-2, which causes Covid-19.

Arjun Poudel

The restrictions imposed to contain the coronavirus spread do not seem to have worked well, if the infection rates–across the country and Kathmandu Valley–are anything to go by.

The national Covid-19 tally on Monday reached 39,460, with 228 deaths.

The Health Ministry said that 899 people tested positive, with seven deaths, in the last 24 hours. Kathmandu Valley recorded 298 new cases on Monday, taking the tally to 5,724.

The government has been relying on lockdowns and prohibitory orders to contain the virus spread. However, health experts have long argued that blanket restrictions are not a solution to the pandemic. They say the decisions–to impose the lockdown on March 24 and then completely lift it after four months without giving a proper thought–were wrong.

What then the authorities could have done?

Apart from testing, tracing and treating, the government should have resorted to seroprevalence surveys, doctors say. According to them, seroprevalence surveys can provide data on the prevalence of the virus in communities, thereby helping the authorities locate hotspots and take various necessary measures accordingly.

“Had such a survey been carried out in some Tarai districts, especially Parsa, Morang, and Dhanusha, we could have known the prevalence of the virus,” an official at the Department of Health Services, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told the Post. “Concerned authorities then could have restricted movements to and from the areas where the cases were high. It could have helped break the transmission chain to a large extent, preventing the virus taking hold in society.”

A serology test examines the presence of antibodies. When a human body is exposed to a foreign pathogen, it produces antibodies in response.

Serology tests look for either Immunoglobulin M (IgM) or Immunoglobulin G (IgG), the two antibodies developed by the body against the virus. The IgM is the first antibody developed by the immune system, so it is detected during the test first, within a week or two, followed by the IgG, which is detected during another test two weeks after the infection.

A seroprevalence survey can provide an estimation on the percentage of people in a population with antibodies against SARS-Cov-2, which causes Covid-19. This then can tell authorities how many people in a specific population may have previously contracted the virus.

After the end of the lockdown on July 21, the Health Ministry said it would perform seroprevalence surveys on around 7,500 people. The authorities, however, have yet to conduct the survey.

“We had entrusted the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division with the task of performing serology tests about a month ago,” Dr Sameer Kumar Adhikari, joint spokesperson for the Health Ministry, told the Post.

Division officials, however, said since they are already hamstrung by manpower crunch, they sought help from the World Health Organization’s country office in Nepal to provide technical staff to conduct the tests.

“We sought the WHO help for technical staff, as it takes a longer time to hire staff from our system,” Dr Basudev Pandey, director at the Division, told the Post, pointing at the byzantine bureaucratic process the government hiring takes. “The UN agency has set the September 4 deadline for applications. We can start the study once we are provided with the staff.”

Doctors and public health experts say a lack of political will from the authorities is largely to blame for the poor response to the pandemic and that the delay in conducting the seroprevalence survey is just an example how government officials are refusing to recognise a looming catastrophe.

According to them, existing human resources serving in health facilities could have been easily deployed for the survey.

Dr Prbhat Adhikari, an infectious disease and critical care expert, said nurses and paramedics can be roped in for the initial process, in which they just need to draw blood from patients and store it properly.

The samples then need to be sent to laboratories, where the presence of antibodies–IgG and IgM–can be detected in blood plasma. While the IgM usually disappears from the blood within a few months after recovery, the IgG can be detected for years.

Two types of tests—an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, also called ELISA and Chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) test–are performed to check the antibody against Covid-19 on participants.

Both tests are considered a gold standard for study of antibodies against the coronavirus, according to Dr Megnath Dhimal, chief researcher at Nepal Health Research Council.

“Seroprevalence tests help us identify the risk and contain the spread of infection,” said Dhimal. “Such studies help us locate high risk areas so that the authorities can declare restrictions on those areas and perform polymerase chain reaction tests.”

The United Nations in Nepal in its April report “Covid-19 Nepal: Preparedness and Response Plan” had listed “strengthening capacity and partnerships for operations research–transmission studies and sero-surveys” as one of the priority preparedness activities.

As one of the priority response activities, the UN called for facilitating lab-based operations research–especially in determining household infection rates, asymptomatic infection rates and seroprevalence.

Even after spending billions–Rs13 billion by the government’s own admission–authorities now appear to be groping in the dark.

Although public health experts have been saying that there is enough evidence to prove community spread of the virus, government officials continue to deny this.

“A seroprevalence study can also be helpful in confirming the community spread,” said Dr Kiran Pandey, a consultant physician at Hams Hospital. “This is one of the ways to perform more focussed tests and pool testing in risk areas, thereby saving resources.”

In pool testing, samples from multiple people are tested on the whole batch. If a pool returns a positive result, the second phase of testing is conducted by breaking down the batch into small groups to identify the infected person or people.

If it shows negative, all individuals in the batch are negative.

In an interview with the New York Times in June, Dr Anthony S Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said US officials were having “intense discussions” about a possible shift to “pool testing”.

“The standard approach to controlling infectious diseases–testing sick people, isolating them and tracing their contacts–was not working,” he said. “The failure was in part because some infected Americans are asymptomatic and unknowingly spreading the virus but also because some people exposed to the virus are reluctant to self-quarantine or have no place to do so.”

The threat level in Nepal may not have reached the US level yet, but what the doctor says does resonate with the situation here–infected asymptomatic people might be spreading the virus and some despite getting exposed to the virus are either not going into self-isolation or lack facilities at home to do so.

“Since seroprevalence test is significant in conducting pool testing, it should be done without delay,” said Adhikari, the infectious and critical care expert. “Also, polymerase chain reaction tests may not detect the virus after two weeks have passed since infection, but a serology test can provide information on the infection by detecting the antibody. Thus it helps understand the status of the virus penetration in society.”

14.68°C Kathmandu

14.68°C Kathmandu