Food

Nepali winemakers, buoyed by demand, are experimenting and innovating in local vineyards

Though most Nepali wines are sweet and fruity, producers are moving towards bold and robust flavours, hoping for a boom.

Thomas Heaton & Krishana Prasain

Kumar Karki rifles through a crate of grapes and selects a bunch to taste. The grapes are small and muddy green, not like the perfect looking ones you can find in stores. They don’t just taste sweet either; they are complex in flavour, for these are wine grapes from German vines.

At the Pataleban Vineyard Resort in Kewalpur, Dhading, Karki is experimenting with growing his own grapes to make wine. He goes through individual grapes, tastes them and oversees crates as they are lugged down vine-lined slopes to a jeep waiting at the bottom. From there, the grapes are taken to a small cellar, where the grapes will be readied for fermentation.

Though Nepal has been producing wine for decades now, Karki’s Pataleban is the first Nepali vineyard to grow its own grapes. Nepali wine is generally made with indigenous fruits, herbs and sugar, tailored to sweeter palates, but with wine imports rising annually, local wineries like Pataleban are researching new ways to diversify the kinds of wine that are produced in Nepal. As increasing numbers of people travel abroad and learn about wine, the demand for more complex varietals is rising and Pataleban is one vineyard attempting to address that demand locally.

Grapes have typically been imported for local production—either in the form of grapes or must (crushed stems, juice and skins)—but this year, Pataleban is picking Phoenix grapes for the first time. The German hybrid grape, bred to be disease resistant, has been a boon for the vineyard. Like all of Pataleban’s grapes, these are the fruit of imported vines, produced after two years of maturation. Some 20 varieties of grapes are grown across Pataleban’s 15 hectares, some from Switzerland and Germany, others from France, Japan and the United States.

The grapes are crushed and the juice is left in fermenters overnight before German yeast is added. It’s perhaps the only Nepali wine made from grapes grown and fermented locally with specific varietals, and without added sugar.

Karki has been growing grapes to make wine for nearly 12 years now, but wine has been around a lot longer.

Fruity tastes in Nepal

Recent decades have seen a flourishing of Nepali wines, mostly red, made primarily from berries. Among the most popular brands is Hinwa, started by Satya Lal Ranjitkar, and made from ainselu (Himalayan raspberries) and chutro, which are barberries.

While the current iteration of the family business started in 1994, Makalu Wine Industries, Ranjitkar’s family has been making wines for far longer.

Satya Lal, a horticulturalist and self-taught winemaker, first learnt about wine in the United States in the 80s. On a visit to Napa Valley, the heart of American wine country, he witnessed the industry in full bloom, leading him to want to make wine when he returned to Nepal.

“There were indigenous fruits that were going to waste here, so his idea was to make wine with them,” said Ashraya Ranjitkar, Satya Lal’s grandson and production manager of Hinwa’s Tamaphok, Sankhuwasabha winery.

Rather than using grapes, Satya Lal set about trying to find the perfect fruits with which to make wine. He tried to ferment just about every fruit—apples, lemons, oranges, plums, even nettles and dandelion.

“It was not a very appealing taste,” said Ranjitkar, referring to a wine made with lemons.

According to Ranjitkar’s father, Maheshwor, Satya Lal successfully petitioned King Birendra in 1985 to create a local industry to promote employment in the region, excusing it from paying excise duty and sales tax for 10 years. The first family wine business was started the same year, called Fermented Beverage Industries.

Satya Lal launched a wine made from oranges, but it failed to take off. Support for the wine industry was short lived, according to Ranjitkar. The king’s edict was eventually reversed by the government and the industry closed down because they didn’t pay their taxes. Wine was then put into the same tax bracket as hard alcohol.

But in 1994, following some deliberation, the family relaunched under the Hinwa brand. Their wine, which is sweet and fruity, is informed by Nepali perceptions of what wine should taste like, said Ranjitkar. Hinwa uses supplemental sugar and water to balance out the acidity and bitterness of the berries. But otherwise, the wine-making process is close to traditional grape wine production.

In the 15 years since it relaunched, Hinwa is now a popular brand of local wine, with the winery producing 35,000 cases of wine, accounting for 315,000 litres per year.

While Hinwa focuses more on berries and fruits, Royal Big Master, produced in Bhaktapur, uses imported grapes for its wines. But it too is looking to create its own 7.6 hectare vineyard in Kavre to produce Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon grapes, with vines imported from India, China and Italy.

Royal Big Master was established just five years ago, in 2014, using Indian grapes from Nashik for red wines and apples from Mustang for whites. But like Hinwa, Big Master keeps its wines sweet, but sugar also keeps prices down because it extends flavour when mixed with water, according to Milan Sharma, Big Master’s sales and marketing manager.

Royal Big Master currently produces 810,000 litres per year, using imported Indian grapes and Nepali apples, according to Sharma, who also says that Big Master is the largest wine producer in the country. The company is growing at a rate of 20 percent annually.

“Quality and price, and people welcoming the growing drinking culture has encouraged expansion,” said Sharma.

The success of Hinwa and Royal Big Master in the domestic market has meant that Nepali wines are in demand, with the domestic wine industry growing by 20 to 25 percent annually, according to Ramesh Prasad Shrestha, president of the Nepal Beverage and Cigarette Industries Association. Out of the approximately five million litres of wine that Nepalis consume annually, a majority is local, produced by around 40 small and large wineries, said Shrestha.

“They might not be meeting standards, but they are looking for ways to improve their quality. There is not a long history of wine-making in Nepal,” he said. In 10 years, Shrestha expects both quality and consumer perception to get better.

This increasing demand for wine can be attributed to a changing culture of drinking, where more women are enjoying alcohol, Shrestha said.

Wine start-up Pure Joy was founded by four women, but hangovers from old stigmas remain.

Co-founder Binita Pokhrel said her parents still tell friends that she is in the juice-making business. It’s similar to old notions of drinking as an unbecoming activity, said Pokhrel.

“But female members of the family have started drinking wine on special occasions and family gatherings,” said Pokhrel.

For Hinwa’s Ranjitkar, Nepal’s emerging middle class and strengthening economy might also have something to do with the rising demand for wine. As men continue to mostly drink whiskey, beer or local alcohols, young women earning mid-range salaries are drinking more wine. Royal Big Master’s market reflects those findings, according to Sharma.

But for upper socio-economic brackets, local wines might not cut it, as the quality still remains comparatively poor. Those in the upper-middle and upper classes can afford imported wine, which tends to cost upwards of Rs 1,200 a bottle. But for those who don’t earn much, Nepali wines, at Rs 500 a bottle, are still too expensive, thus leaving the market to middle-income families.

“For domestic wine, it’s 18 to 45 year olds and mainly ladies who drink our wines,” said Ranjitkar. “A lot of males go for hard drinks, or beer. We have a long way to go to improve our wine standards so people from all strata of Nepali society will try our wines.”

Emerging and imported tastes

Imported wines, however, are a luxury for most locals. But with people earning more, disposable incomes are also getting bigger.

Among the most prevalent imported wines is Jacob’s Creek, found in hotels and restaurants across the country, selling at a recommended retail price of Rs 1,500 per bottle.

SPG Trading, one of industrial conglomerate Sharda Group’s companies, is the national importer for Pernod Ricard, the second largest wine and spirits company in the world, which owns Jacob’s Creek and Campo Viejo. SPG imports both brands in thousands.

Jacob’s Creek was first introduced to the Nepali market 15 years ago, according to Ramesh Ghimire, assistant general manager for SPG. The wine can be found around the country in supermarkets, stores, restaurants and hotels.

“There are more than a hundred imported brands in Nepal. Nepal’s best wine is from Australia, though—and Jacob’s Creek sells more because of its quality and price,” said Ghimire.

Ghimire said SPG controls about 70 percent of Australian wines imported to the Nepali market, with “more than” 20,000 cases of Jacob’s Creek per year, amounting to between 135,000 and 180,000 litres. SPG also imports “more than” 10,000 cases of Robertsons wine—90,000 litres—from South Africa. Exact data is “confidential”, he said.

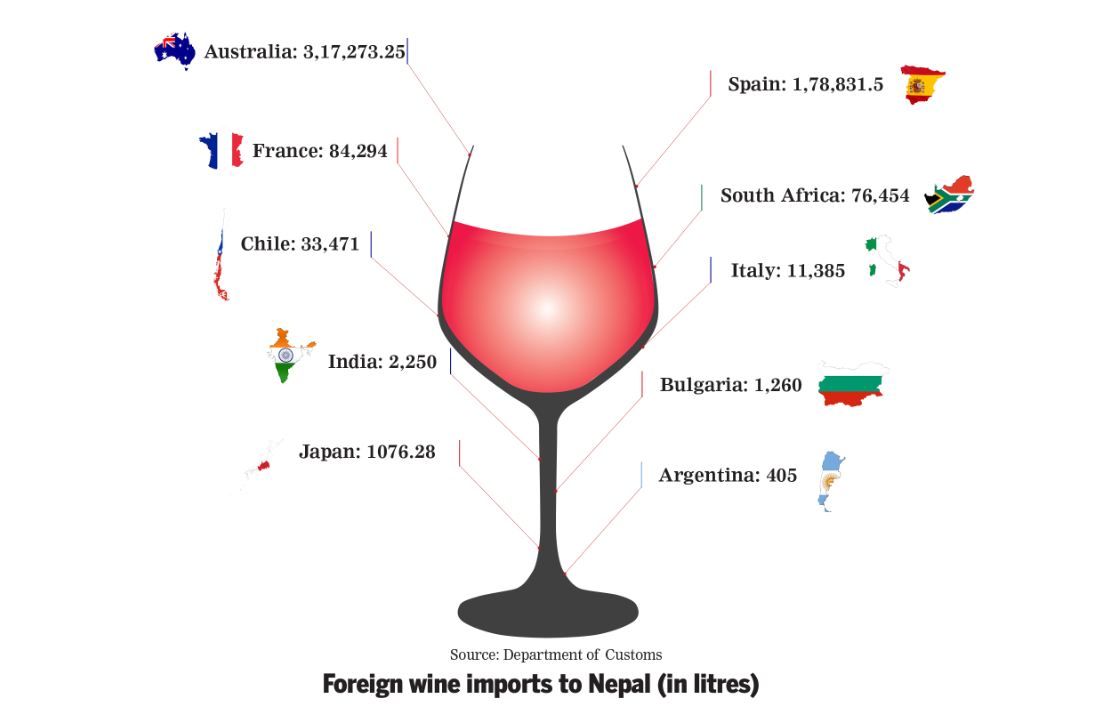

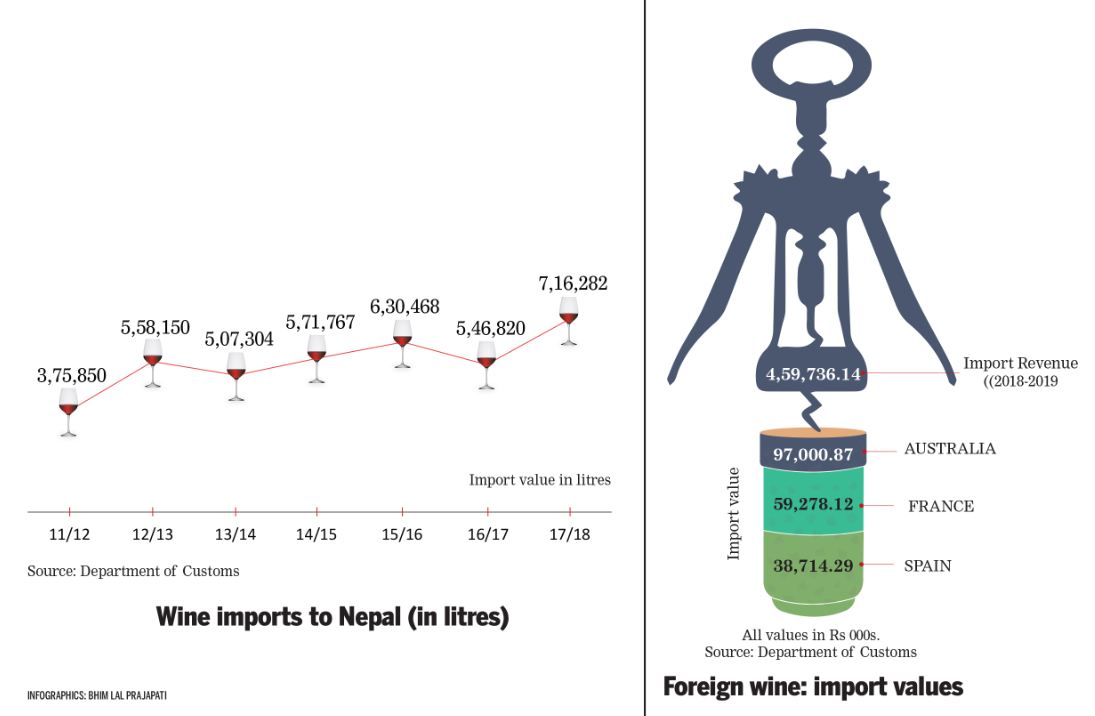

“There’s no competition for Jacob’s Creek,” said Ghimire, but just last year, the country imported almost 950,000 litres of wine and grape must in the 2017-18 fiscal year. Wine accounted for more than Rs 580 million in government taxes and duties in the same period, according to the Department of Customs. More than 355,000 litres of Australian wine alone was imported in the same period.

Alongside SPG, the restaurant Vesper House in Jhamsikhel is another major importer of wine in the country, bringing in an average of 72,000 bottles a year in six containers of 12,000 bottles each. Vesper, however, specialises in high-end wines from Spain, France and Italy, supplying them to most of the Valley’s upscale restaurants and hotels for the past 10 years.

Sales executive Susan Kunwar says they’ve gradually increased their numbers and diversified their portfolio.

“We’ve been trying our best to introduce something new to the industry,” said Kunwar.

Vesper has brought in different wine varietals in the past and is now experimenting with biodynamic wines. They will soon start importing Chilean, Argentinian and New Zealand wines, he said.

While Vesper has available approximately 80 different labels, costing between Rs 1,100 and 110,000 per bottle, the most popular is by far their Vesper-branded wine, which is produced by various regional wineries in Italy and branded with Vesper’s label. This wine is offered by several restaurants and hotels as house wine, said Kunwar.

But the majority of Vesper’s clientele is either foreigners who appreciate different varietals or Nepalis who’ve travelled overseas and come back with an understanding of wine.

Alex Muktan, Vesper’s founder, said they’ve made a concerted effort to educate Nepali palates when it comes to wine.

“We bring master sommeliers into the country at least twice a year and do events,” said Muktan. Those events include training staff from Vesper and other places on the nuances of wine.

But Vesper does not stock any Nepali wines.

“They are slowly progressing, it’s improving, but it’s still not up to international standards in terms of quality and taste,” said Kunwar.

Future prospects, through the grapevine

Ranjitkar of Hinwa has been keeping an eye on what is going on at Pataleban Vineyard and its successes.

“I’ve started experimenting with grapes,” said Ranjitkar. “The process is very much, the only difference is the sugar content.” The final product, while not perfect, left him and his friends “pleasantly surprised”.

One day, if Nepal were to have its own viticulture industry, Pataleban should get the credit, said Ranjitkar.

Another brand looking into locally grown grape wines is Pure Joy’s Pokhrel. She hopes to produce wines with both seasonal Nepali fruits and grapes grown from imported vines. Having already planted some 500 vines from Switzerland in Dhulikhel, Pokhrel will soon produce red wine with these grapes, but keep white wines fruity and local—with bananas, mangoes and oranges.

For Pataleban, despite more than a decade of growing grape varietals, the product is still not perfect, according to chairman Karki.

Because the country is so young in terms of being a grape-growing region, Pataleban is experimenting outside of its main vineyards to see where the best area might be.

“We have planted several different varieties within a 45-minute drive of Bardiya. We have also placed 30 vines in Mustang. We are trying to see how these will grow,” said Karki.

The first issue is avoiding disease without using too many pesticides, then it’s about making good wines, said Karki. Several international winemakers and viticulturalists have advised Pataleban with wine-making in the past, but last year it enlisted tropical viticulturist Wolgang Schaefer as a regular consultant.

In June, oenologist Schaefer told the Post he saw a “great future” for wine in Nepal, especially in the realm of sustainable agro-tourism. Tropical Viticulture Consultants, Schaefer’s company, has also advised Monsoon Valley Vineyard in Hua Hin, Thailand, which he said attracted 120,000 tourists last year for wine tasting, elephant vineyard tours, and fishing. This indicates a possibility for tourism in Nepal too.

“I could imagine a similar thing in Nepal, because there are a lot of foreign tourists already,” Schaefer said, on a call from his home in Germany.

However, there are challenges with growing wine in the region because the season is shortened by the monsoon; this means the growing season is relatively short. But German disease-resistant hybrid grapes have been successful thus far, because they are able to use Dermox, a ripening accelerant, so harvests can happen before the rains arrive.

Pataleban’s topography is extreme, with grapes growing between 860m and 1,500m. “One can safely call them the steepest vineyards in the world,” said Schaefer. “The spectacular terraces of Visperterminen in Wallis, Switzerland, ‘only’ have an altitudinal difference of 500m.”

In Europe, wine produced from terraced areas fetch more on the market for their concentrated flavours. So, for wine produced in this “extremely steep terrain”, the flavour potential is exciting.

But that will require a lot more work from vineyards. Even in Europe’s flat topography, growing season requires 50 hours of machinery-based work; steeper, terraced, terrain requires about 200 hours of work, with the help of helicopters and machinery. Here, in Nepal, specifically Pataleban, the difference is there is no machinery and the vineyards are steeper. This disparity in workload, Schaefer said, exemplifies the sheer amount of work required at the Kewalpur vineyard, but also a potential for employment within the local community.

But, for anything like that can happen, the wines need to be perfected. That could, with proper investment and equipment, take about five years, according to Schaefer.

Pataleban stocks its own wine, and provides its products to an extremely limited number of outlets, as it produced just 35,000 bottles last year. It has the capacity to produce up to 200,000, which it aims to achieve in the next five years, said Karki.

One of the few places that currently stocks Pataleban is Vino Bistro, where owner Antoine Garet believes that the vineyard is constantly improving.

While the varying climes of Nepal are largely unlike other wine-growing regions around the world, there is great potential for grapes, such as chardonnay, cabernet sauvignon and syrah, because they are hardier.

But, knowing exactly what will be the best grapes for the region is hard to know, Garet says.

When India’s homegrown industry was starting to take off, planting grapes like riesling seemed untenable, he says. That said, the quality of the riesling that now comes from the country is impressive, he says.

“Indian wine is just ten years old and you can taste the improvement,” said Garet, who believes Nepal could mimic India’s success.

Tropical viticulturist Shaefer returned to Pataleban’s vineyards at the start of July, to see how the grapes and vines had fared over the course of the year. Having been marooned at the Kewalpur vineyard overnight, because rains flooded the road out, he came to understand the challenges of wine-making in Nepal first-hand.

“It’s a good experience. Now I understand why you have to harvest the grapes in June—it’s impossible in monsoon,” said Schaefer. “But we got a good vintage, some very nice wines are fermenting.”

But, when it comes to putting a timeline on when Pataleban will consistently produce quality wines, it may be about five years.

One of the most intriguing things was the quality of the muscat bleu, which he says has a distinct rosey bouquet.

“There are very few red wines that have a strong flavour, but this one does,” said Schaefer. “For me, this could be Nepal’s symbolic wine.”

20.81°C Kathmandu

20.81°C Kathmandu