Food

Big beer companies have a monopoly on the market. Now some beer lovers want to change that.

Nepal has long been lager land for beer lovers, with no real other options available. But a small group of craft brewers are optimistic about the future of microbrewing in the country..jpg)

Thomas Heaton

Hemendra Bohra discovered the wonders of beer while studying at Harvard University in the 90s. At Boston’s pubs, he drank lagers, pale ales, amber ales, IPAs, stouts, and porters with his Nepali friends, dreaming of one day opening up his own brewpub in Kathmandu. But when Bohra came back to Nepal in 2007, he realised that brewing beer was going to be harder than he thought.

Not long after he arrived, Bohra learned that the government had all but stopped issuing beer and liquor manufacturing licenses. He sent a request for the minutes of the Industrial Promotion Board meeting that decided to cease issuing licences, but was refused access. He probed further, issuing a Right to Information request, but a lengthy wait left him disillusioned.

While he waited for the information to be released, he enrolled in an online brewing course with the American Brewers Guild in 2009 and did an internship at a brewery in the US. He never received a response from Nepali officials.

Recent decades have seen a rise in microbrewing and craft beer. Apart from beer’s heartland in Belgium and Germany, countries like the US, Canada, Australia and India have caught on to the marvels of craft beer, both in terms of taste and in business. A microbrewery, also called craft brewery, brews beer in much smaller batches than larger commercial breweries, focusing more on flavour profile and brewing technique. They also are generally independently owned.

Nepal, however, remains largely unenlightened—not just to craft brewing, but to beer’s diversity itself. The local brewing industry, controlled by giant companies, is saturated by pallid same-same lagers, strong beers and a single Nepal-brewed red ale. For anything else, customers must rely on comparatively expensive imports.

In 2007, Bohra began to actively lobby the government to open up possibilities for a new craft beer industry. While he waited, dejected by the lack of reception, he busied himself with his own beers.

“I started some homebrewing and tried growing some hops and malt at home. But I eventually lost interest because it wasn’t going anywhere,” Bohra said in an interview with the Post.

Seven years later, in 2014, his dreams were rekindled. He met Sushil Khadka, then CEO of the restaurant chain Bajeko Sekuwa, at an Entrepreneurs for Nepal event, and the two got to talking about beer.

The restaurant chain was among the biggest consumers of alcohol, predominantly beer, in Kathmandu, so Khadka had already been looking into brewing beer at one of his outlets.

“They had all the connections in the industry and I helped them with the technical part,” Bohra said.

Once the pair got together, they began pursuing a brewing licence, even meeting with the minister.

Mahesh Basnet, then minister of industry, was on board with the idea, and so was the head of the National Planning Commission, according to Bohra.

“It was basically these two who pushed really hard. The sad thing about that meeting was that the people who were most opposed to it represented the Confederation of Nepalese Industries [CNI] and the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industries [FNCCI],” said Bohra.

Both these organisations represent Nepal’s big business houses, most of whom own breweries themselves. Bohra believes they were afraid of competition but, despite their protests, the proposition was pushed through, thanks to Basnet’s support.

“I don’t know why they opposed it. In the US, craft beer represents just two percent of the total volume,” says Bohra. But the government was ultimately on board, according to Khadka, with no resistance in their drive to bring microbrewing to Nepal.

Following the successful lobby, guidelines were drawn up.

.jpg)

Bohra worked closely with the ministry on the guidelines. Restricting licences for microbreweries to larger cities—or certain restaurants and hotels—came up multiple times. But Bohra’s desire for an open market, where everyone can brew beer, was eventually accepted. “We were pushing to make it free for all,” Bohra said.

The guidelines dictated that restaurants or hotels selling microbrews would need at least 120 seats, according to Khadka, and would have to be sold by tap. No bottling beer for outside sale. While initially brewing licences would be issued to restaurants in main cities, the ministry eventually opened up to smaller places to have the breweries too, such as tourist hotspots like Namche Bazar. The alcohol percentage was to stay under seven percent, according to Khadka.

The Post requested more information from the Department of Industry, but was denied access to the drafted guidelines because the document had not been sent to Parliament.

“But, right after that, the government changed and then the Indian government imposed the blockade. We lost momentum because of all these incidental hardships,” Khadka said.

But those hardships weren’t what stopped microbrewing in Nepal. There was some “influence” on the ministry, according to Khadka, which led to the Parliament calling the scheme “unfeasible”.

“They essentially said it was a stupid idea and that nobody should pursue it,” Khadka said. “Because of the blockade, the big players got time to play.”

A sub-committee was eventually formed to oversee and investigate the set-up of microbreweries. As a result of what both Bohra and Khadka suspect as big industry players influencing the process, the sub-committee found that “microbreweries were not viable in the present context”.

The more thorough justification given, says Bohra, was the government’s inability to find a way to tax microbrews. “Stopping new brewers from coming in didn’t make any sense,” he said.

Bohra, along with many in the brewing community, believes that the sub-committee was influenced by the big breweries.

Then-minister Basnet, however, says that it was political, not business, opposition that killed the microbrewing licence. He had convinced everyone—including representatives of big breweries—that it was a good idea, he said, because opening up to microbreweries was part of running a free market.

But the parliamentary sub-committee that put an end to the microbrewing license was led by the opposing political party. “It was a political move,” Basnet said.

Brewing behemoths

Since the block of a prospective microbrewing scene, the power relationship—and the variety of available beers—has remained the same in the brewing industry, barring one or two new beers coming into the market under existing licences.

Licences, even for larger breweries, have not been issued for at least three years, as the government put a stop to issuance on August 2, 2016. Additionally, the licences were tailored to a large-scale brewing industry, with a threshold of just over one hectare of land for bottling plants and 2.7 hectares if the factory is built for bottling and brewing. Among the 15 criteria potential breweries have to fulfill, a Rs 500,000 guarantee would have to be paid to set up a brewery. While existing breweries could pay Rs 300,000 to expand an existing institution, they have similarly been stopped from expanding, according to Department of Industry officials. The beer sphere, therefore, has remained very much the same.

Kusang Tamang, co-owner of Nepali Craft Beer Distributors, believes that people deserve more choice in their beers. Tamang’s business primarily distributes Sherpa beers in kegs, but also imports the UK brand BrewDog.

“We have less than one percent of Nepal’s beer market, so the big beer companies don’t consider us a threat, or even competitors,” Tamang said.

But there are areas where small distributors of speciality beers face challenges.

“They have this thing called tie-ups,” said Tamang. “The big brewer pays others [restaurants, bars and liquor stores] some amount of money per year to carry their beers exclusively. The contract doesn’t say anything like that, but it is worked out in such a way that they have to sell so much that they don’t have the capacity to sell other brands.”

Such tie-ups pay well—up to half a year’s rent or even more, depending on the location—in return for selling 500 cases of beer. Tamang says shops get more financial incentives for using branded signage and reserving shelf-space. They are also given credit, so they don’t have to pay for beer they plan to sell until they run out of stock.

.jpg)

“They must have really low production costs, or they just want to drive out competition first and take over the market share. They have a lot of money, especially Gorkha Brewery,” Tamang said.

The Post contacted Gorkha Brewery to set up an interview regarding contracts incentivising exclusivity, annual production and the events surrounding the lobbying in 2014. The brewery accepted an interview, but failed to turn up, then asked for questions via email, and when emailed, refused to answer, saying that the information was “sensitive” and “confidential”.

Gorkha Brewery is the most dominant brewery in Nepal, owning a lion’s share of the Nepali beer market. According to Carlsberg Group’s 2018 annual report—Carlsberg Group owns 90 percent of the brewery—Gorkha controlled a 63 percent share of the Nepali market. There are a handful of other players, such as CG Breweries, United Breweries, Yeti Breweries and Himalayan Breweries, but Gorkha is by far the largest, producing Gorkha, Tuborg, Carlsberg, and San Miguel.

“For liquor stores, it’s profitable, because they don’t have to pay up front. On top of that, they also get money for putting beer on the shelves. The breweries run special promotions, like buy 10 cases, get one free. I’ve even heard of buy-one-get-one schemes. That could be because [breweries] want to get rid of expiring stock, or they just want to flood the market with their products,” Tamang said.

Tamang believes that it is through these schemes and offers that Gorkha Brewery has managed to capture the market, ever since the mid-90s. “They made sure that whoever came into the market didn’t have much of it,” he said.

When such a large share of the market is controlled by one brewery, it can be difficult to compete, says Tamang. Generally, when shops’ or restaurants’ contracts expire, Gorkha approaches them again. In one instance, Tamang teamed up with other smaller brewers to provide a package that was better than what Gorkha was offering. While the deal was accepted, he said providing such packages on a larger scale proved unviable.

The tie-ups don’t hurt Sherpa Craft Brewery all that much since they have a level of brand loyalty. But for Tamang, that’s not the point. “We don’t believe in exclusivity. What we would like is to have all bars sell all beers,” he said.Evolution Beverages’ managing director Ashish Pradhan says that tie-up contracts, while not illegal, are “unfair for the customer”.

“It’s a problem throughout the world, not just in Nepal,” said Pradhan.

Thomas Schlau, head brewer at Tigers Brewery in Butwal, says it’s hard to make a mark and even keep beer on the shelves.

Tigers Brewery, which brews Tensberg and London Ice, has a difficult time putting its products on the shelves because of the stiff competition. One of Gorkha Brewery’s latest beers, Himalayan Dragon, is being pushed in places that already sell inexpensive strong beers by providing theirs at an even cheaper cost.

“There’s always a competitor's marketing team trying to push out the competition,” Schlau said.

The Nepali market, in general, is not loyal to particular brands either. This means their product is often replaced or pushed out.

“They [customers] are not buying the beer because of the taste. First, they look at the price, then they look at the taste,” he said.

Because Nepal has long had limited offerings when it comes to beer, much of the population has limited tastes. And because many Nepalis are mostly concerned with price, there is an anomaly that only occurs in this country, said Schlau.

“It’s the only place in the world that strong beer costs less than regular lager. How can it be cheaper?” he said. “Strong beer is the main beer for production, but you don’t get sufficient profit from it.”

The profit comes from “premium” beers, brewing in numbers and saturating the market, says Schlau. Premium beers are targeted towards tourists and more affluent Nepalis. But for Tigers Brewery, the brunt of its profit still comes from its Nepal Tiger strong beer.

A taste for craft

Beer is a broad term for a diverse range of different grain-based fermented drinks, such as stouts, ales, pilseners, wheat beers and, of course, lagers.

Bohra, the man who lobbied the Ministry of Industry, credits Tigers Brewery’s Schlau with being the first to brew craft beer in the country. Schlau, along with his Nepali partners, brewed two varieties under the brand Coblenzer in 2009, with a contract to brew at United Brewery. While the beer seemed popular, he says, mismanagement and a lack of proper equipment meant they were forced to stop production just a few years after they started.

Because the brunt of the industry is tailored to vapid varieties of beer, that’s what many people seek. Schlau says he believes it may take some time to educate people on what could be available. And this education begins with the fact that not all beer is yellow.

For Tamang, who is also an avid homebrewer, it is mostly about educating people’s taste buds. Having once run a pub that sold imported beers, the general Nepali taste was evident when he sold beers such as India Pale Ales (IPAs), which have a broad flavour profile and challenge uninitiated palates.

Even the beer Tamang distributes, Sherpa Craft Beer, which claims to be the first craft beer in Nepal, had trouble introducing its red ale to an uninitiated populace. He says there was one instance when a patron, who had perhaps never tried a craft beer, sent an IPA back because he thought it had gone bad.

Another thing is knowing the difference between bottled and pulled beers.

“What’s craft and what’s draught? People don't know much about craft beer, so our big challenge is educating people and telling them why our beer is slightly more expensive than other beers,” Tamang said.

Now, however, bigger breweries are getting into the keg trade, which means there could be more pulled beers available in pubs and restaurants. But at the moment, a majority of restaurants and bars across the country only serve bottled beers, with barely a handful of beers on draught available.

Across the border, India’s $3 billion beer industry is similarly dominated by a strong-beer trade. But that hasn’t stopped a vibrant craft beer industry emerging throughout the country. The city of Bengaluru has come to be synonymous with the craft brewing movement, with 53 breweries in the city alone, according to Nikkei Asian Review.

Since the first brewpub opened in Gurgaon in 2008, India’s 150 craft breweries still constitute only a tiny fraction of the $3 billion industry. Nepalis are able to taste some of this craft beer too, as the Indian brand White Rhino is imported and distributed throughout the country.

Even with a vibrant craft brewing scene across the border, Nepal hasn’t quite followed suit. At Cheers Enterprise, which home-delivers both domestically and internationally produced liquor, lagers still account for about 70 percent of beer sales while wheat beers account for 20 percent, says general manager Minesh Rajbhandari. Indian Pale Ales, stouts and other more obscure beers account for just 10 percent.

The strong flavours of the darker beers and IPAs’ “punch in the face of the hops” are off-putting to the Nepali beer-drinking population, he said. It can take some time to get used to these flavours. However, the relatively approachable sweetness of the wheat beer is starting to prove popular.

“They [Nepalis] have started preferring wheat beers. First, it was Hoegaarden, then Kronenburg Blanc, and more recently Bira 91,” said Rajbhandari.

Even CG Breweries, an arm of the CG conglomerate, launched its ‘Magna’ wheat beer in 2018 under the Nepal Ice brand. Even though bigger breweries like CG are also getting into different varieties, most of Nepal still seems to enjoy strong and cheap, instead of flavourful, beer.

“It should be an occasional, cultural thing, but a lot of people just drink to get drunk,” said Rajbhandari. “People don’t want to spend thousands and not get drunk.”

Towards a more flavourful future

Despite the consensus that many look to cheap and strong beers to get drunk, rather than opting for flavourful brews, Bohra still holds hope for the future. He hasn’t brewed in five or six years, he said, but he’s optimistic.

Both he and Khadka told the Post that they believe there will be a scene in the future if there is strong leadership and a desire to make it happen.

However, behind the scenes, there is already plenty of interest in the potential industry, according to Basnet, the former minister.

A group of Mumbai businessmen in the craft beer industry visited Nepal three months ago, with plans to open up a smaller brewery. “The foreign industrial people have come and they want to make fast decisions,” Basnet said.

Because they want to expedite the process, Basnet thinks the 2015 guidelines could be followed and, if some initiative is shown, it could be a relatively quick process. If there is enough drive to instate the guidelines, Basnet said it could take about two to three months to push it through Parliament.

However, current Minister of Industry Matrika Prasad Yadav has not heard of the Indian businessmen and was not even aware of the framework’s existence when he spoke to the Post. Still, he remains “positive” about the future of microbrewing here in Nepal.

“We will continue with the process and consult with the prime minister and the finance minister,” Yadav told the Post.

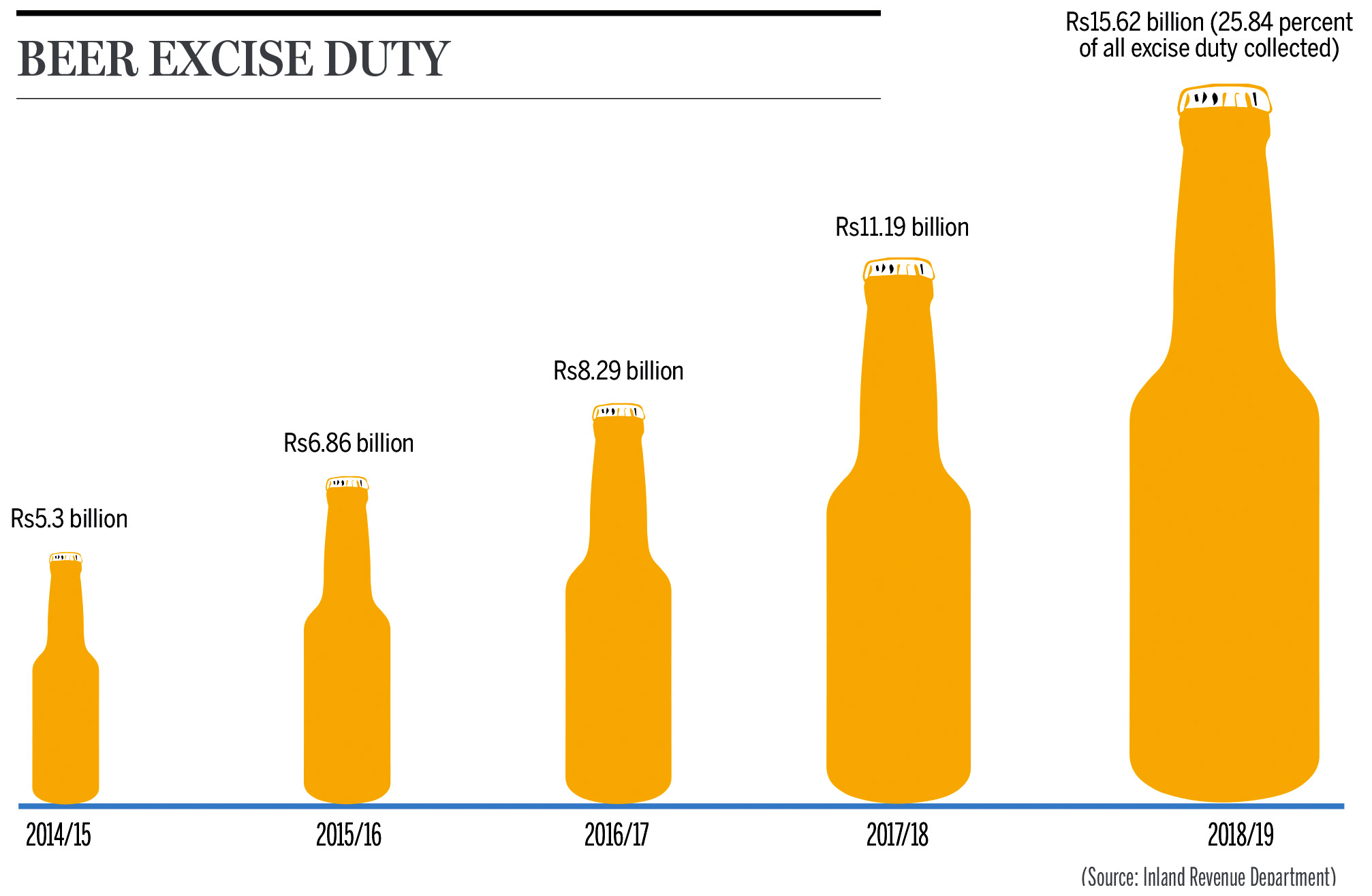

Yadav’s main concerns, however, are similar to what’s been expressed in the past—primarily, how the Inland Revenue Department will tax beverages. But it’s been suggested that they do so on an average per-sale basis.

Pradhan of Evolution Beverages does not see the potential microbrewing sphere as a threat to businesses like his or big breweries. While importers such as himself are extending the variety of brews in the country—Evolution Beverages imports Asahi, Singha, White Rhino WIT and IPA—he aims to refine consumers’ palates and open them up to the colourful world of dark stouts, and red, brown and amber ales, not just plain yellow lagers

“If the big brands can brew beer and sell it all over the world, then why can’t the little guy have a legal outlet to sell their stuff?” said Pradhan.

The burgeoning brewing sphere, although still small, is trying to do things legitimately, Pradhan says, and they should be able to.

“The people who want to brew, or are trying to brew, don’t want to do it illegally, but there is no legal provision,” he said. “Big businesses will never go out of business because at the end of the day, some people just want to drink lagers and stick to that style.”

***

Tika R Pradhan and Rajesh Khanal contributed reporting.

9.7°C Kathmandu

9.7°C Kathmandu