Fiction Park

Rain

It starts yonder, over the slopes of Chandragiri. Yonder to the West where Chandragiri with its majestic elephant head guards over our valley like a sentinel. Pluffywite clouds, scattered about but only yesterday, collude over the elephant head of Chandragiri, doing kanekhusi in a language we do not understand.

Dipesh Risal

June 16, 1841

Nepal Valley

It starts yonder, over the slopes of Chandragiri. Yonder to the West where Chandragiri with its majestic elephant head guards over our valley like a sentinel. Pluffywite clouds, scattered about but only yesterday, collude over the elephant head of Chandragiri, doing kanekhusi in a language we do not understand. Soon they collect into imposing masses. The wind picks up. Swirl the clouds northward. The clouds gather moisture, purpose. They darken. By the time they arrive over Thapathali, they have become a single impenetrable slab of grey, an eternal mass stretched outward, reaching the surrounding hills and beyond. In fact, much beyond, looming densemysterious over all of Nepal in shades of blueblack fringed in deep gray. A pregnant promise permeates the air. But there is also a hint of malice. It is only midday, but the thick cloud cover makes us think it is two ghadis after sunset.

Gone is the soul-scorching heat of the bare sun from a few days ago. But a sweltering stickiness still hangs heavy in the air. Our perennial crows and sparrows are unusually quiet. Galli dogs roam restless, in silence. Indeed the entire valley is quiet. A tense quiet, the animals the trees the hills the gods all waiting...

Then

Milik... milik...

Jhilikka

Angry slivers of lightning flare over Mangal Bazaar, Tudikhel, then Kirtipur. The light rushes off to the hills, makes the peripheries of Nepal glow incandescent for fleeting moments: now Phulchoki, now Nagarjun and now Kakani flash with wrathful white light, penetrating the all-encompassing darkness.

The briefest of silences. Followed by

Dhadyang... Dhagyang...

Dhadyannnngggg

Suddenly, no human or animal is in sight. We yield the valley to Nature. We know from experience: this is her time. Her time to assert herself – her Peacock Dance – and us mortals step aside in stupefied awe. We huddle inside brickhouses. The dogs and cows find shelter in the nooks of temples and paatis. The birds sneak deep inside brickenholes and trees. The majestic fury of lightning and thunder continues for many pals. Celestial playmaking, this: the lightning flash darts, the thunder catches up, the lightning flash swerves erratic, the thunder responds in kind, having echoed back from the hills.

Another silence. This time a more relieved silence, like the spent end of a fierce battle. But the silence is somehow also pregnant. It is as if our collective memory tells us the drama can end now, or continue for many more acts. We certainly are not satiated. Having shaken us, Nature has somehow increased our anticipation.

We watch, then, as the utter silence lengthens. The dark gray clouds scurry hither. The deep blue clouds slither yon. The silence makes the performance more intimidating… almost demonic.

The third and final act starts slowly. The first few tentative drollops of wetness land randomly upon the vegetation behind our houses, causing a loud rhythmless clatter. The slow, heavy pitter patter bends the long corn leaves in unnatural angles. The twirlyswirls of the lahare cucumber and the fragile soybean leaves shake occasionally on contact. It is a reunion dance, a sensual dance, but the plants seem offended by the awkward first steps. Meanwhile, the large splats of rain hit parched tiles and bricks of our chowks and temple squares, break up into a hundred small droplets and creating ugly scars like Ajima’s smallpox face. The scars quickly evaporate into nothingness, warmed by stored heat in the brickwork. This first contact of water and earth also leaves behind a pleasant gift: a subtle organic smell of soil roused by moisture, the smell of dust not yet turned to mud. A fresh smell that permeates the air, shoots into our brain, tingles the very core of our identity, an imprinting forged by a millenia-old love affair with the wetness falling from the sky every year.

In time the pitter-patter grows louder, more frequent, and picikingupspeed quickly reaches a crescendo as Indra finally appears soaring across the sky, and slits the clouds open with his vajra.

And lo, the heavens pour down upon us. Nourishing rain falls in massive diagonal sheets of gray onto Nepal. The Purna Kalash is overturned, and the Soma spills freely. Soma, replenisher of the dry, parched earth. Soma, agency of life, nourisher of grain, ensurer of harvest. Soma, elixir of the heavens, the seed of gods, shared without reserve with us mortals for but a precious few months of the year.

The unrelenting downpour washes away the sweltering moist heat smothering Nepal. In its place comes a gentle breeze. It is not exactly cold, but the steady wind and drenching wetness somehow gets to our bones. Some of our bent elders even pull out siraks from storage, cocoon themselves within, and continue gazing out windows with cataract eyes clouded by seeing too much:

jham jham jham jham

jhum jhum jhum jhum

The rain falls on the vegetation. The initial hesitancy of first is gone. Now the leaves the branches the flowers all sway in sensual abandon, hypnotized by the swooshing chorus of dense rhythmic pitter-patter:The rain falls on our galli dogs, who meander around the streets, then curl up into balls anywhere it takes their fancy, heads tucked snug under flanks, soon sound asleep, as unmoved by the fierce rain as they were earlier moved into hiding by the thunder.

The rain falls on our pigeons. They stir, fly about desultory among the temples and squares, get drenched. Changing their minds, they return to the temple struts, rafters and eaves, shake their bodies violently, succeed partially in warding off the water, then starevacant from their perches with frazzled feathers and spiky necks. The crows and sparrows remain in hiding.

The rain falls on Singu hill, where the eternal eyes of Swayambhu gaze serene. Swayambhu, the self-existent, of flame, of crystal, who sees it all, and forgives it all with utter, utter compassion.

The rain falls, too, on our rain gods, whom we had beseeched earlier to send us rain. It falls on Pashupati, whom we had lustrated with holy water last month so he would cause rain. It falls on Macchindranath’s chariot, which we had pulled into Jawalakhel just last week, in the hopes of getting rain. It falls on all the subterranean serpents and their king, Karkotak, to whom we had already paid the proper homage so he would not block the rain. It falls too on the scarce statues of Indra scattered through the valley. Indra, original ancient god of rain, whom we have somehow forgotten in the last thousand years. But we ask Indra to worry not, for we will be sure to worship him in a few months time with a festival entirely to his name (and he knows why we will have to unfortunately tie him with ropes through the weeklong festivities).

The rain falls on little boys and girls who run giddy and half naked around our chowks. On tippytoes they reach up to the skies with inspired gazes and try to touch the deep mystery of those thick molasses swirling over the valley. But their mothers shout at them, summon them inside. They will now not catch a cold. But alas, they will also not catch the infectious ancient magic of rainclouds which was just within their reach. Next year they will not reach up on tippytoes again.

The rain falls on the courtyards of our bahas and bahis, our tols and gallis, our sattals and patis. It washes away the accumulated dust the feces the rotting rice. The rain cleanses us inside and out.

But the rain also washes away, little by little, the silay that joins the bricks of our temples and houses. It washes away the rich nurturing soil from our terraced fields. Little by little, it claws at our statues and temples, miracles sculpted in wood metal stone by ancestors. Little by little, it washes away a bit of ourselves, in rivulets and streams trickling through our gallis, then collecting in our chowks, pouring off into Manohara and Tukucha and Nakkhu, before gathering momentum in the unified torrents of Bagmati and Bishnumati at Teku. The willing swirling waters then carry it all away to Balkhu, to Chobar, and finally out of the valley through the swirling waters past Karyabinayak and through the hills carry our souls, our essence, our history, carry it all, for better or for worse, as they always have and as they perhaps always will, all, all towards the south, towards Ganga, towards Kashi.

∫∫∫

Jung Bahadur looks up at the rain. When is this useless downpour going to let up? He is itching to practice his sword and wrestle with his brothers out in the open but the rain has kept him indoors for days. He looks sideways at Putali Nani, who lies languid upon his chest, exhausted. He used to think she was bewitchingly pretty… it used to get him every time. But now she lay sound asleep, mouth slightly open, her foulish warm breath hitting him repeatedly on the neck and assaulting his nose… hints of garlic and onions. He twitches his shoulders instinctively. Putali Nani slides off, slumps clumsily onto the carpet. He lets her be. He thinks instead about the Darbar gossip she had shared earlier. He does not give a damn about feminine gossip, but it often contains nuggets of useful information. The Senior Rani’s recent tantrums, running off to Pashupati one day and to Hetauda the next… perpetual threats and constant ultimatums, perhaps she has truly gone mad. And Surendra, such barbarism, such lunacy from a mere boy of eleven. He makes my life living hell, but I can handle it and I will turn it to my advantage one day. But his newlywed wife...how could he throw her, a child of eight years, into the pond?… and that too for the second time? Meanwhile, the spineless Rajendra allows all this to happen under his nose… maybe even encourages it. The father, son and mother all raving lunatics in their own ways, pulling the country apart in three directions. How can a country be run like this? To hell with the whole lot of them! Nepal needs another Bhimsen Thapa. A strong man who can crush the Darbar and rule with an iron fist. I wonder who it is going to be? Whoever it is, I need to be on the lookout for him, and the moment he arrives, I will align myself to him, and rise as he rises...

Surendra looks up at the rain. From his balcony above Mohan Chowk, the evil dark clouds appear very low in the sky. The rain falls down in fearful dark torrents. Surendra slowly shifts his eyes towards the roof of Basantapur tower. Vulture be gone… vulture be gone… Ah! It is still there, perched menacingly above the gajur. Sensing Surendra’s presence somehow, the vulture turns and stares directly at him with fiendish bulging eyes. Soon it stretches its naked pink neck, spread its ugly wings, and scoop down, aiming directly at his eyes. Ohgodohgodohgodohgodohgod. Up above, the entire celestial weight of the sky is coming down, lower and lower, unrelenting, pressing down upon his head, shoulders, chest... He tries to move, but is gripped by fear. Ohgodohgodohgodohgodohgod. Beside him, someone is standing with folded arms, pleading with him about something. Vaguely he catches a few words: nightfall… only a child... pneumonia… forgive and forget… Is that person real? Or another apparition? He has no time to decide. He is being crushed under the weight of the entire sky, crushed into a paste like the insect he is. And the vulture is picking at his eyes and his brains through the holes of his skull. And Bhimsen Thapa’s ghost comes again, and try to “talk some sense” into him. Ohgodohgodohgodohgodohgod.

Brian Hodgson looks up at the rain. The reading room at the Residency is a perfect roost to take in the sweet melancholy of these Monsoon rains. He is worried about the Nepal Durbar. News of our recent losses in China has rekindled the martial Goorkha Spirit. Goaded by the Pandeys, the Rajah talks openly about alliancing with Punjab and Persia against us. For all his feebleness, the Rajah has a handsome grasp of Asian affairs and of the next chess move that would place his Durbar at an optimal geopolitical position… If only he would dispense half as much cunning to put his domestic affairs in order. The Rajah believes he is playing a winning game in the domestic front too, but he fools himself. Ere long, some courtier will leap up unexpected and checkmate him at his own game, perhaps fatally.

Laccho looks up at the rain. The raindrops hit her directly on the eyes and it hurts, so she looks down again. The water in the pond laps dangerously around her shoulders. She has to stand rigidly straight otherwise the water will get to her nose and into her ears. At the same time, she is trying not to lose her foothold on the slippery bricks underneath: the bricks are smooth, and the soles of her feet can feel a layer of moss along the surface, which makes the bricks even more slippery. One false step and I will die. The water had wrinkled the tips of her fingers a long time ago. It is not exactly cold, but she is beginning to shiver. Why is this happening to me? They told me everything would be better after the wedding. They said I was going to be a queen of this awful country someday. So why is he still treating me like this? And why does Ajima not come to rescue me? Why does the Senior Queen not come? Isn’t she from Gorakhpur too? How could she stand by and let that beast do this to me? Night is coming soon... the darkness is sure to confuse my balance and kill me… she looks up cowering towards Basuki Naag on top of the massive pole in the middle of the pond…Or maybe that serpent will eat me first… They say it sometimes leaps out of the pole and swallows small children whole under cover of night…

Dhan Sundar looks up at the rain. Smiles. Very good. If it continues like this, the fields will be ready for transplantation in two weeks. He thinks of the merry march to the fields, his brothers sisters uncles neighbors shouting laughing all the way, the terraced fields lying serene, brimming with water, the sky reflected blue and white on the undisturbed surface of each lush green terrace, the soothing feeling of wet mud squeezed in between his toes, the croaking frogs and chirping crickets, the copious drinking, the thick lush sensual smell of new vegetation, the open flirting among young and old. He thinks of the song his uncle was sure to sing during sihnaajya. In anticipation, he starts humming:

Bhaa pila jhaya la ji bona yaney la

Mana ja chiva lise ola hnaam

Aayale bhaju haaya sihnaajya ni oney

Jyamiyata baji nake maa ni hnaam...

∫∫∫

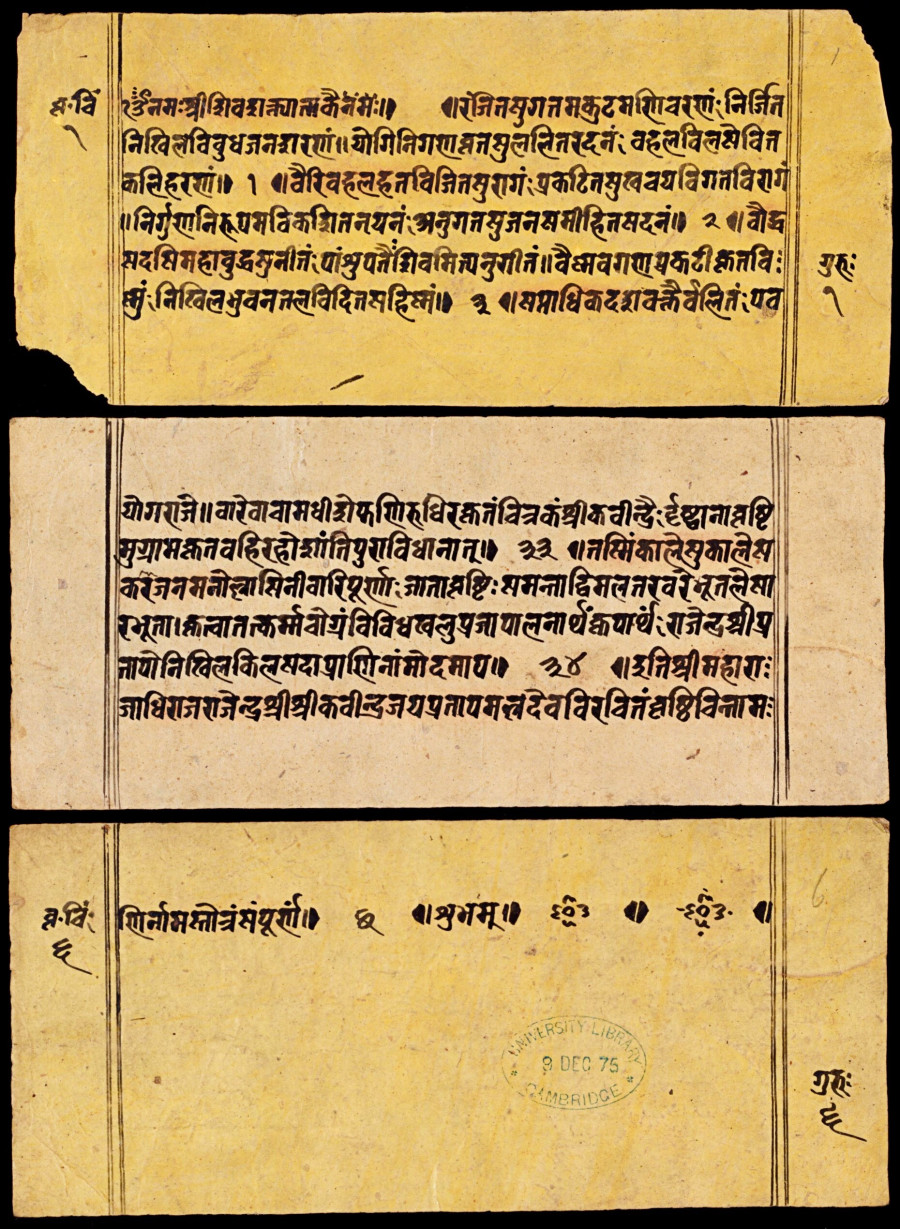

Image 1: The first and last pages of a copy of Vrishti-Chintamani, a charm of rain in 34 stanzas by King Pratap Malla.

Image 2: Bronze statue of Indra, Kathmandu, 15th century CE.

Closing text in Nepal Bhasa: Excerpt from a sihnaajya (rice transplantation) song, published in Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns by Siegfried Lienhard.

A version of this story is available at dipeshrisal.com.

9.56°C Kathmandu

9.56°C Kathmandu