Fiction Park

The Beginning of the End of Jung Bahadur

Jung Bahadur was not a happy man. He had just hosted a resoundingly successful hunting trip for the Prince of Wales.

March 7, 1876

Beldandi, Near the Western India-Nepal border

Jung Bahadur was not a happy man. He had just hosted a resoundingly successful hunting trip for the Prince of Wales. The Prince had openly proclaimed that he was pleased with the frenzied khedahs for wild elephants and the personal shots at lions and tigers at close range. Jung Bahadur could rightfully claim that he had paid off the debt incurred him long ago when he visited London, a guest of Queen Victoria, the Prince of Wales’ mother. But none of it mattered.

Even the lazy rhythms of the Tarai forest, the toasty brown smell of dust and manure, the hints of pungent mustard oil from the drying pinaa in the nearby village kolhu, the breezy friendliness of the Tharus, all of which used to invariably cause a nostalgic surge of youthful vigor in his blood, today failed to lift the jaded and dissipated spirit of Jung Bahadur. Instead, his mind swarmed with the insults and bad news he had endured while hosting the Prince of Wales’ hunting party at Banbasa. For one thing, the two British surgeons with pale long faces at the Prince’s camp had said quite confidently that his arteries were clogging up. It was only a matter of time before...

Jung Bahadur kicked his horse into a canter to create a distraction, for his mind was unable to process the alien and unproductive thought of death. His eyes, glowing with a cold blue light like balls of phosphorous, never wavered in their gaze locked onto the tips of his horse’s ears.

That first meeting in the jungle with the Prince. Him on foot, the Prince on horseback. The indignation of that insult still stung deeply. In his zeal to show off the temporary bridge his soldiers had thrown across the Sarada river for the Prince’s visit, he had forgotten to account for the fact that this arrangement necessitated the Prince being on horseback, while he was forced to walk the short distance from his camp on foot. Dhirey, as his Eastern Commanding General in charge of camp, should have foreseen the gaffe, and should have taken steps to prevent it. But Dhirey was too busy sulking gloomily, the way he had been doing these last few years... the ingrate.

...and after all he had done for the British, to learn that they had named the Prince’s goddamn horse Jung Bahadur! The Prince had disclosed the name to him personally... almost proudly. That’s what made it worse. He expected Jung Bahadur to be grateful about the name. That’s how the British trampled all over Asia: a gift of a few Purdey and Winchester rifles to the small kings and princes, some choice words of complement in refined language, then stick a knife in their back and bleed their nation dry with taxes, bribes and outright sedition. And when tempers simmered down and memories faded, they expected the feckless locals to quietly turn into obedient slaves! But not in Nepal. Not on my watch! Jung Bahadur twitched his torso out of deeply ingrained habit and adjusted himself on the horse’s saddle.

And just like that, the bane of his existence, the words of his father from so long ago, returned and ricocheted in his head:

...gnat gnat gnat gnat gnat...

These words had started to haunt him in recent months with alarming frequency. He let the words gnaw at his already wounded ego, suffered the mental anguish in silence for almost a ghadi. He slouched his shoulders so uncharacteristically that it surprised everyone in his hunting party and troubled the few who still cared about him. His horse cantered on, oblivious of the inner turmoils of his master.

Suddenly, Jung Bahadur turned toward Dhir Shamsher, who was close behind as usual, and in fact watching him intently.

Did you send the gift of fruits to the Prince’s camp?

Yes I did, Daju.

Well, what did you send?

Dhir Shamsher frowned almost imperceptibly. He looked straight ahead, letting a thought play out in his mind, resolved it, turned around, and asked the Mir Munshi with a bit more briskness than usual:

Tell us about the fruits that were sent.

The Mir Munshi galloped forward and recited respectfully from memory: two buckets of mangoes, one bucket of pomegranates, peaches, pears, dried dates and papayas each, and one sack of oranges, Maharaj.

Dhir Shamsher waved the Munshi away. Jung Bahadur said nothing. Dhir Shamsher said nothing. The horses continued on with the smart canter Jung Bahadur had initiated, which was not a problem for man or beast on this entirely flat trail so close to the ample, winding expanse of the Sarada riverbed.

Just as the party turned a bend on the trail, Dhir Shamsher’s sharp eyes noticed a large, strangely shaped tree straight ahead, it’s one thick branch shooting off at an awkward angle from the base of the trunk, giving it the appearance of having grown sideways, probably a result of some trauma endured during sapling days. Other trees and shrubs had grown up in abandon above and around the sideways branch, providing deep cover.

Hark! Dhir Shamsher now noticed a mass of yellow and spotted black curled up within the same deep cover of the tree. Instinctively he reached down with his right hand found the holster took out the Purdey pistol steadied his shooting hand with the other while the leopard leaped out of the darkness of the tree and pounced straight at them with gracefully ferocious muscular strides. When the leopard was fifteen feet away from Jung Bahadur, Dhir Shamsher shot it between the eyes.

The leopard lost its balance and skidded awkwardly to one side of the trail, a heap of flailing legs and twisted body, plume of dust in its wake. Dhir Shamsher galloped up to the stillthrashing body and put another shot through the leopard’s chest at close range, ending the beast’s agony.

Jung Bahadur caught up with Dhir Shamsher, and exclaimed rather weakly:

The scoundrel almost finished me off! It was hiding so well. I saw nothing until it started pouncing toward me.

Dhir Shamsher looked at Jung Bahadur with innocent surprise:

Daju, you... didn’t see it?

Of course not! It was hiding so well within those dark branches. Remember what Mama used to say? Jungey’s eagle-eyes... If even a bit of the leopard was visible, I would have seen it. My eagle-eyes have never betrayed me.

With that, Jung Bahadur confidently turned the horse around and galloped onto the trail. Dhir quickly followed his older brother and caught up with him.

Daju... this stretch of jungle has always been dangerous. Stay on the inside of the group. I will take the outer flank with the Bijuli Guards and we will protect you from all sides.

La la, nakaraa!

With that, Jung Bahadur twitched his torso again and continued on, cold steely eyes steadfastly latched back onto the tips of his galloping horse.

Not even one ghadi had passed. Jung Bahadur suddenly startled and pulled hard on his horse’s reins. As the horse reared in surprise, Jung Bahadur blurted out:

There! Another leopard!

Dhir Shamsher stopped and scanned the thicket his brother was pointing to.

Daju... th.. that is just a tree-stump.

Jung Bahadur squinted into the thicket for quite a while.

No, look there... Hmm... Ahem...

Jung Bahadur grunted. He squinted again, desperately trying to find some evidence that would resurrect his slowly fading dignity. But it was just a tree-stump. He quietly tugged his horse into a gentle trot. His eyes had already lost their usual intense focus. Wide open and slightly panicked, they darted around vacantly, as if mirroring an internal turmoil as he tried to latch onto some non-existent mental mooring. His face was frozen in mild anguish.

For the first time in his life, at the age of fifty-nine, Jung Bahadur felt old. His poor eyesight... the recent bouts of hallucination... perhaps they had to do with his head not getting enough blood. Could that in turn be due to clogged arteries? Perhaps he should ask Resident Girdlestone to re-initiate discussions for that darned second visit to London, just to take care of his ailing heart. And he should have bought more opium balls... he was almost out.

...gnat gnat gnat gnat gnat...

∫∫∫

Dhir Shamsher was genuinely worried. He was trying not to care. He knew that he really should not care. But Jung Bahadur was his older brother after all. He had played with his Daju on heaps of rice straw all along the banks of Bagmati during lazy golden autumn afternoons, when both were half-naked urchins. Together, they had experienced the decadent pampering that only a rich Mamaghar can dole out while growing up in Mathabar Singh’s Baag Darbar. He had taken bullets for Jung Bahadur, and Jung Bahadur in turn had made sure that Dhir’s political fortune rose with his own. Dhir Shamsher somehow forgot the fatal blow to his lineage dealt by Jung Bahadur when he recently rearranged the Roll list. Forgot too, the daily insults heaped by the entire Jang clan on the Shamshers on account of their lack of wealth and prestige. And the blatant favoritism Jung Bahadur had piled onto his dearest sons Jagat Jung and Jeet Jung in recent years, at the expense of Jung Bahadur’s own nephews, Dhir’s sons. Dhir’s obdurate sense of pride, usually a force like a bull in heat, vanished in that moment. For reasons incomprehensible to himself, Dhir Shamsher thought only of his dear Daju of childhood, and of Jung Bahadur’s salt which he had eaten most of his life. Then he said softly:

La, Daju, now I insist that you stay here, on the inside. I will guard you on the left. The jungle is the thickest and most dangerous there.

∫∫∫

Excerpts from the author’s forthcoming historic fiction novel “Jung Bahadur’s Nepal” can be sampled at www.dipeshrisal.com. The description of Jung Bahadur’s eyes as “balls of phosphorous” are from William Howard Russell, a British Journalist reporting from India in 1857.

∫∫∫

Images:

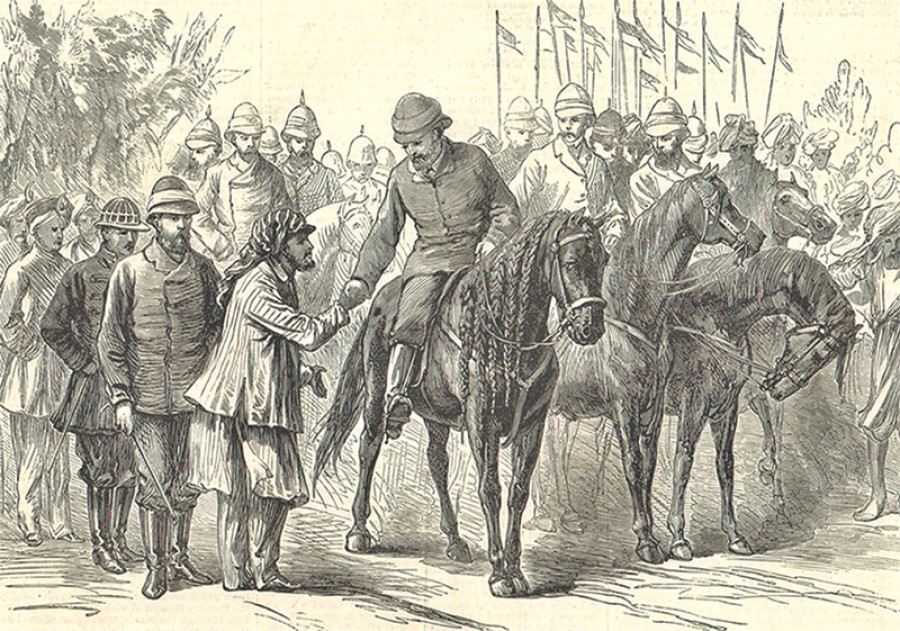

I. Jung Bahadur with the Prince of Wales during the Tarai hunting expedition. From the Illustrated London News, March 25, 1876.

II. A rare portrait of Jung Bahadur by William Simpson from the same hunting expedition.

III. The horse ridden by the Prince of Wales in the Tarai. From the Illustrated London News (1876).

7.12°C Kathmandu

7.12°C Kathmandu

%20(1).jpg&w=300&height=200)