Editorial

Timely verdict

The ruling on ‘sidhakura’ can be a wonderful place to start a conversation on free speech in the digital age.

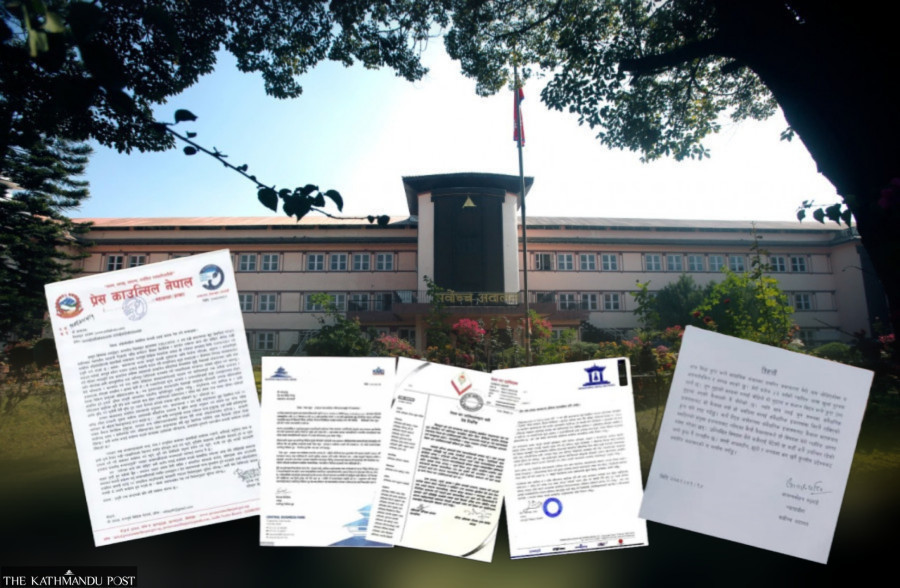

On April 26, 2024, sidhakura.com, an online portal, disseminated a series of malicious audio-video content involving the chairs of two media houses. The fake content even dragged the Supreme Court, citing that the two chairs had met incumbent and former SC justices and senior advocates to dismiss over 400 corruption court cases. When the misleading content spread, the judicial body immediately responded, launching a suo moto contempt of court case against the portal’s publisher and editor.

After months of investigation, the court on Sunday issued a final verdict and showed the prison’s door to the guilty. In addition to the portal’s publisher and editor, who got a prison sentence of three months each, another person, who supposedly conducted the infamous ‘sting operation’ on the portal’s behalf got six months in jail. Such harsh sentencing was due, and it gives a clear message that anyone who peddles false news in the name of journalism will be severely punished. The timely verdict also draws a clear line between free speech and disinformation and misinformation.

The online portal’s claims were based on false premises and ambiguities. First, without any regard for media ethics, the editor and the publisher sensationalised the content, relying on an unverified audio clip provided by a third party. Second, when the Supreme Court and Press Council Nepal summoned them to be present at the court with evidence to substantiate their reports, they failed to do so.

The sidhakura content unfortunately represents one of many cases of fake news that have surfaced in Nepal with the advent of new forms of technology, which in turn undermines democracy and the rule of law. Whether on social media platforms or traditional media outlets, disinformation intended to mislead people and misinformation with outright lies have become all too common. The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) has escalated the problem with the help of deepfakes—audio recordings, video clips or images replicating someone else’s identity using AI tools to spread false information. Deepfakes have been used not only to damage reputations but also to ‘report’ on events that are impossible in real life. In the recent tragic flooding and other natural disasters, deepfake videos simulating various kinds of calamities have been circulated, either to get views and likes or to spread fear. Fake news and deepfakes have also affected elections in many countries this year.

Nepal’s Electronic Transaction Act, the umbrella law covering such cases, is limited in scope, primarily focused on traditional forms of crimes like digital fraud and identity theft. It doesn’t address emerging threats brought about by artificial intelligence. A new law to incorporate these has thus become vital. As important is sensitising people about the consequences of defaming other people through news outlets or social media platforms. The precedent set by Sunday’s ruling will help.

While the media must be free to investigate and report on sensitive issues, this freedom cannot be misused to spread baseless rumours. Sunday’s verdict can be a good place to start the much-needed conversation on the regulation of various kinds of media. This debate will have to be extensive and nuanced as it is so easy to err in this case, either on the side of too much caution or too much liberty.

16.73°C Kathmandu

16.73°C Kathmandu