Editorial

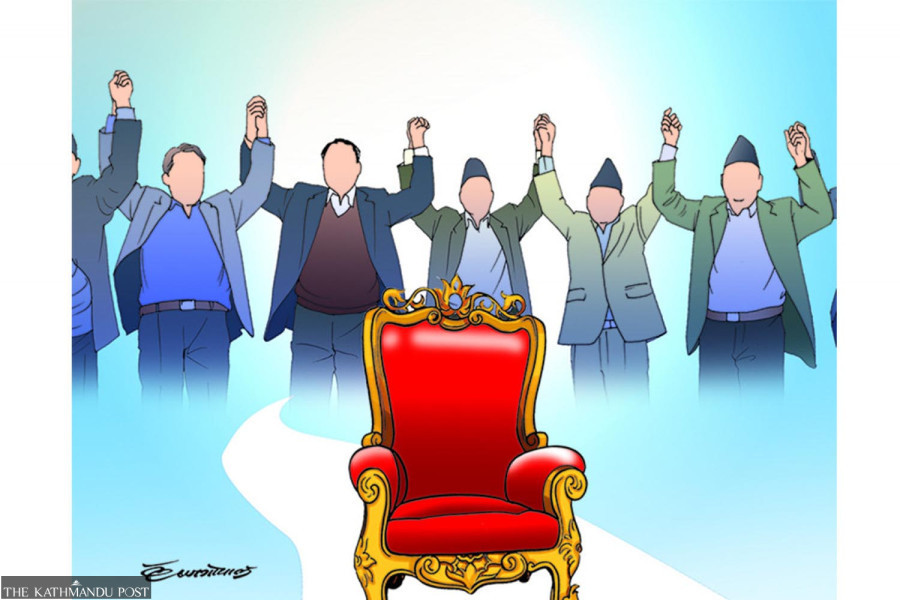

Parties or personality cults?

One sphere where the ‘Afno Manchhe’ culture has really thrived is the political parties of Nepal.

Nepali political parties of the Left, Right and Centre never tire of speaking about democracy. Their concern is often about democracy being in some kind of danger, although it is mostly a case of false flagging. But there is one kind of democracy they rarely talk about—the intra-party sort. Practising internal democracy seems much more difficult than seeking it elsewhere.

A couple of party conventions in the past few months have highlighted the lack of internal democracy among Nepali political parties. The Janata Samajbadi Party Nepal (JSP-Nepal), which concluded its three-day ‘unity general convention’ on June 12, elected Upendra Yadav as chairperson. Although the party announced its central committee members and central executive committee members after a month of the convention, it has failed to pick office bearers. Likewise, the CPN (Unified Socialist), which completed its six-day ‘national convention’ on July 5, elected Madhav Kumar Nepal, Jhala Nath Khanal, and Ghanashyam Bhusal as chairman, senior leader, and general secretary, respectively, through consensus among the party’s top leaders. However, the party has yet to name its 206 central committee members and 18 office bearers.

Once Yadav of the JSP-Nepal was elected to the chair unopposed, he halted the process to elect the office-bearers and central committee members, scheduled for June 13. Twenty-three candidates—17 men and six women—had filed their candidacies for the five positions of vice chairpersons, and six were vying for two posts of general secretary. Twelve aspirants—nine men and three women—had filed their candidacies for the three posts of deputy general secretary. Similarly, the Unified Socialist has yet to appoint 206 of 299 central committee members and 18 of 21 committee members in addition to finalising standing committee and politburo members. Party insiders say the top brass was busy scrutinising the backgrounds of the aspirants before making a final selection. But scrutinising may mean picking ‘yes’ men and women, especially considering the volatile nature of these parties which are either splinters from a big party or have seen their colleagues break away to form other parties.

Apart from these rather fringe parties in Parliament, those that are more mainstream also struggle with the question of internal democracy. The Rastriya Swatantra Party’s joint meeting of central committee and parliamentary party set the tone for the party’s cult culture, with Rabi Lamichhane picking officer bearers considered close to him. There have also been controversies regarding an alleged manipulation of the proportional representation list to include near and dear ones of the party top brass.

The situation in the top three parties—Nepali Congress, CPN (UML) and Maoist Centre—is no better. The Congress reflects a perennial vertical division of the Deuba and Koirala camps; the UML is increasingly being consolidated around the “father” figure of KP Sharma Oli, and the Maoists remain as enamoured as ever by the authoritative personality of Pushpa Kamal Dahal. With individual preferences rather than democratic values ruling the roost, the parties sustain on a feudal system offering handouts, or “tika” in the local parlance, to the sycophants while pushing away those who work hard and question the top brass. If there is one sphere that has seen a thriving “Afno Manchhe” culture—which anthropologist Dor Bahadur Bista so eloquently critiqued in his book Fatalism and Development—it is the political parties of Nepal today.

13.38°C Kathmandu

13.38°C Kathmandu