Editorial

Provincial bottlenecks

The crises in provinces arise from the duplicity of political parties.

Nepal's adoption of federalism was never a wrong move. We needed it to devolve power to the periphery and democratise governance, and we have had a decent track record on these fronts. Despite the successes, we have also had some damning consequences of federalism—the devolution of coalition culture that is the hallmark of government formation at the federal centre. This has given an excuse to the critics of federalism to claim that it is an unsuitable and unsustainable governance model.

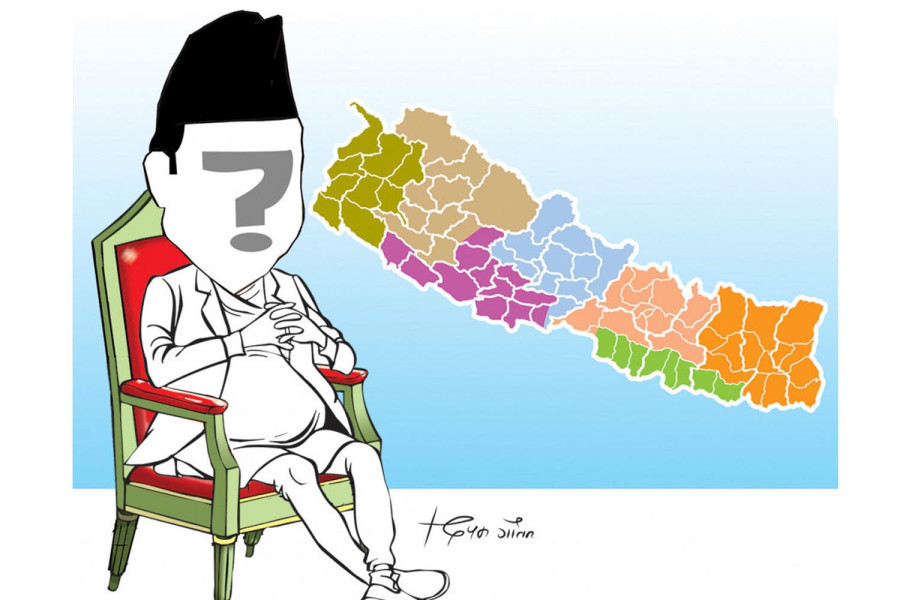

At a glance, their claim seems to be true: No provincial government is a stranger to coalition culture and the cycle of making and breaking governments. In this cyclical process, there is one province or another undergoing a coalition problem at any given point in time. The latest such provinces are Koshi and Sudurpaschim, and they are certainly not going to be the last.

The current series began with Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal changing his government bedfellows just a year after settling down with the Nepali Congress. While the new coalition is now up and running at the centre, the provinces are now showing the ripple effects. This adoption of the coalition culture of the centre was never the intent of federalism. This arises from a paucity of political morality among the contemporary political parties in Nepal, especially those at the centre. Each of the three main parties—the Nepali Congress, the CPN-UML and the Maoist Centre—is working behind closed doors to outdo the other. Coming to the fray is the small fish—Madhav Nepal's CPN (Unified Socialist), punching above its weight.

On Thursday, the Unified Socialist, with just four members in the 53-strong Sudurpaschim provincial assembly, took home the chief ministerial post. Dirgha Sodari was appointed the chief minister with the support of various parties: Maoist (10), UML (10), Nagarik Unmukti (2) and Independent (1). Such a travesty of democracy is unthinkable in political culture with even a paraphernalia of morality. But since a party with just 32 members leads the government in a 275-strong government, Socialist's greed does not appear an anomaly. The Socialist using Sudurpaschim as a new bargaining chip at the centre also does not look out of place considering the lack of morality among contemporary political players in Nepal.

In the Koshi provincial assembly, Chief Minister Kedar Karki is using all possible means to stick to the post even after he has been relegated to the minority. Lately, he has written to the Speaker requesting him not to allow the opposition's resolution motion against him. Interestingly, he had won the chief ministerial position by joining hands with the dissident forces within his party and the opposition UML. Now that the UML has joined hands with the Maoists at the centre, he has fallen between the cracks. But his minority position has not stopped him from trying to crawl back to power. Such duplicity would be considered deplorable in a democratic political system led by morality. At the risk of sounding repetitive, the Post maintains that the bottlenecks at the centre and the provinces result from duplicity and deceit among political parties and is not an inherent problem of federalism.

10.12°C Kathmandu

10.12°C Kathmandu