Editorial

Ruction in provinces

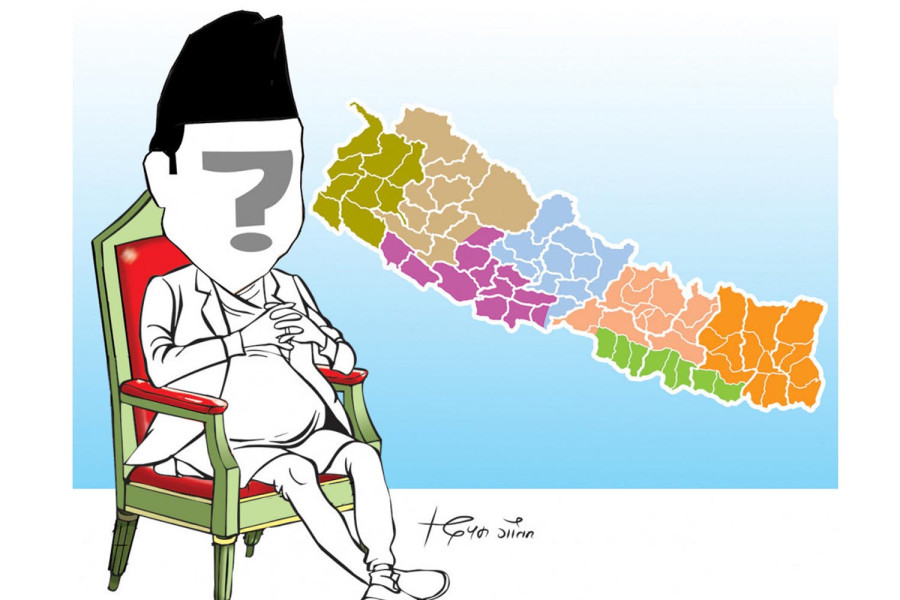

The current provincial governments are no more than offshoots of federal-level politics.

The seven provinces are the beating heart of the country’s new federal system. We often forget that Nepal has always had central and local level governments. If the goal was only to strengthen them, as some advocates of a "two-tier" federal setup would have it, there would have been no need for a federal system. Provinces are the glue that holds the other two other tiers together. Yet the provinces of the new federation have been consistently undermined. They are not adequately equipped in terms of staff and other resources. Nor do they have the requisite laws to function autonomously, as envisioned by the new constitution, in what is a big error in judgement on the part of the national parties and their leaders.

But the provincial political leaders have not helped their own cause by always blaming the federal government for their ills while often not doing even the bare minimum to justify their existence. One reason for this dysfunction is the paucity of institutional memory—after all, the provincial governments came into being only in 2017. A lot of learning is simply a matter of trial and error. Another reason is the centralised mindset of the ruling class, both at the centre and out in the provinces.

The recent unravelling of the Maoist Centre-UML coalition in Kathmandu sent ripples of instability down to the provinces. Their governments will now also change, barely two months after the last change. This goes to show that the current provincial governments are no more than offshoots of federal-level politics. The leaders of the big parties have not trained their provincial-level operatives to think for themselves. They are rather trained to be servile to the central leaders. Another problem is the absence of strong regional parties to keep the national parties honest. It is not surprising that the province where the regional parties are the strongest, Madhesh, also enjoys the most autonomy.

But what we saw in the Sudurpaschim Province a couple of months ago was heartening. At the start of February, the UML-led government in the province fell when the Nagarik Unmukti Party, a regional ethnicity-based outfit, refused to give the UML chief minister its vote of confidence. If regional parties can have such a decisive role, their power will grow over time and the provinces they govern can achieve more autonomy. There is no reason that similar regional parties cannot emerge over time in other provinces. For instance, the ongoing protests in the Koshi Province over regional identity could very well morph into a strong political movement tomorrow.

Even in India, provincial politics took a long time to take hold after the departure of the British in 1947. The early days of the republic were dominated by what was largely a single party rule of the Indian National Congress across the length and breadth of the country. But, over time, regional parties started coalescing around issues of language and ethnicity and challenging the Congress rule. This is thus not a time to despair about Nepal’s weak provinces but to nurture the spirit of the federal rule in order to develop strong provinces in the long run.

16.46°C Kathmandu

16.46°C Kathmandu