Editorial

Untimely consensus

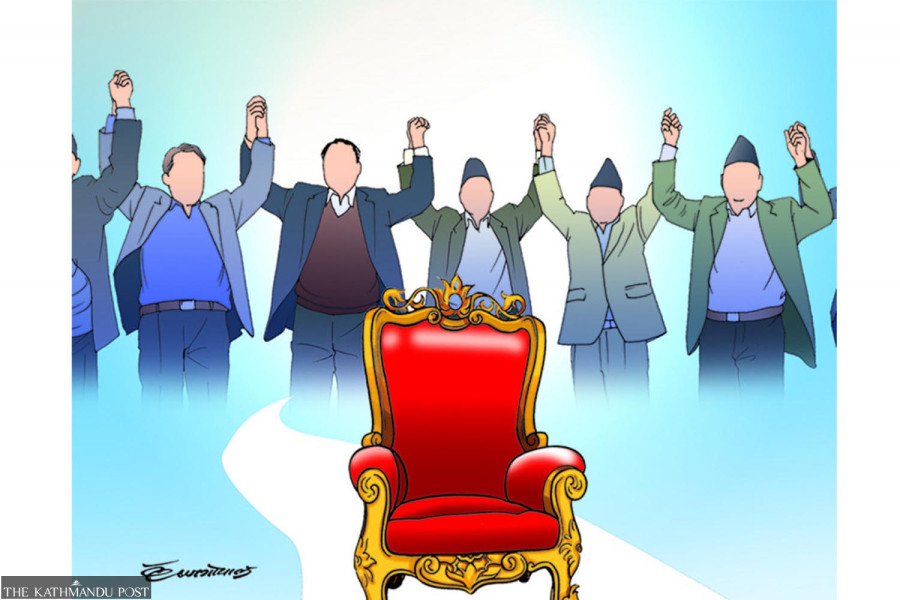

Forging a “national consensus” in the absence of national emergencies is an affront to multiparty politics.

The idea of ‘national consensus’ started taking shape when the political parties were in a collective fight against the autocratic monarchy in the aftermath of King Gyanendra Shah’s coup on February 1, 2005. Back then, the parties had a single goal: to bring sovereignty back to the people. When Shah subsequently announced the restoration of the dissolved parliament, the political parties again had no option to work together to chart out a new political course for the country. The unfinished business of the peace process that started in 2006 also gave them the impetus to keep working together. Then, in 2008, the country elected its first Constituent Assembly, whereupon there was still a need for the parties to collaborate in order to draft a new national charter and to see the peace process to its logical end. But Nepal turned a corner when it got a new constitution on September 20, 2015, even though the process of transitional justice, a crucial component of the peace process, remained incomplete. That was when the idea of national consensus should have died a natural death. The country had charted a definite course and it was now up to the political parties to compete to win public trust and govern on the basis of this trust.

Yet the idea sputters on. It is now being invoked not to conclude the transitional justice process, which would have been a worthy goal, but to prolong the tenure of a government led by the leader of the third biggest political party in the parliament. In normal course, the Maoist Centre Chairman Pushpa Kamal Dahal, whose party has just 32 lawmakers in the 275-member assembly, would not have become the prime minister. Yet he managed to coax and cajole his way to power. And now he dusts off the idea of national consensus so that he can continue as the government head. This is not to single out Dahal though. Given the brand of self-serving politics Nepali political leaders have pursued of late, perhaps the likes of Sher Bahadur Deuba and KP Oli, the heads of the first and the second largest parliamentary parties respectively, would have done the same where they were in Dahal's shoes. Yet the idea of forging national consensus when there are no emergencies in the country is an affront to multiparty politics. It would be dangerous if the idea became synonymous with three or four top leaders coming together and forging a deal convenient to their realising their individual political ambitions.

The election of the country’s President is a competitive process. The head of the state will be chosen by an electoral college composed of the members of the federal parliament and state assemblies. It would be wrong of a handful of leaders at the centre to try to dictate the voting intent of the members of these sovereign chambers. There is also no guarantee that a consensus President, if one can be found, will stay within constitutional bounds. Plus, can any candidate be ‘politically neutral’ in a society thoroughly steeped in politics? Both Dahal, who insists on political consensus and Oli, who is as adamant on ‘political consensus in favour of a UML candidate’, are wrong on this account. If national consensus gets a bad rap, tomorrow, when the country really needs it, say in some emergency, the public won’t be convinced that it is being pursued with the right intent.

8.26°C Kathmandu

8.26°C Kathmandu