Editorial

Women in lead

Nepali society is more open to women’s leadership than established parties would have us believe.

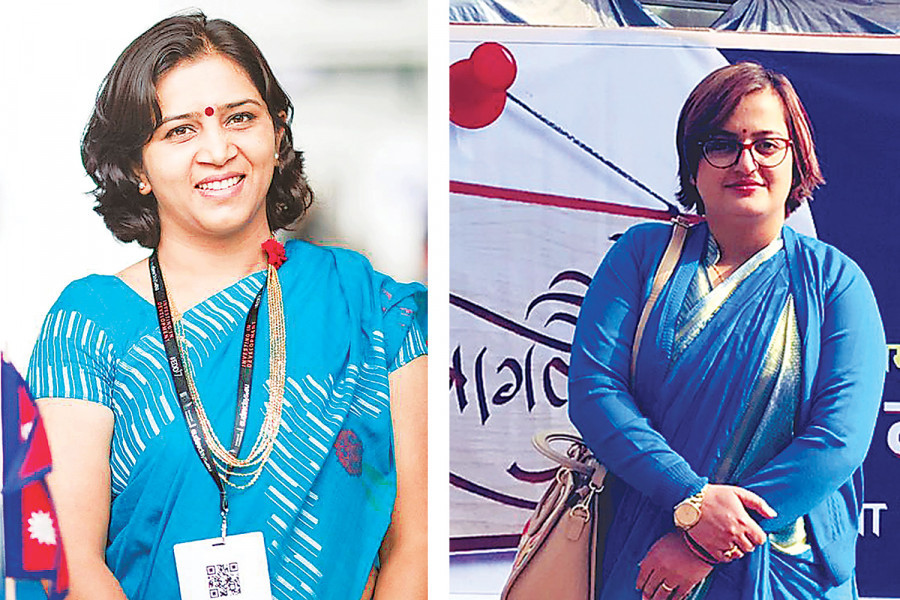

After faltering multiple times in its early days of “alternative politics”, especially after its inconvenient merger with the formerly Rabindra Mishra-led Sajha Party, the Bibeksheel Sajha Party is trying to make a comeback. Not only does the party appear keen to revive the original ideals floated by its late founder Ujwal Thapa. It has already given a strong message by deciding to rebuild under the leadership of two women. The party unanimously elected Samikchya Baskota president and Ranju Darshana general secretary through its first general convention held last week.

The comeback Bibeksheel Sajha aims is not going to be easy in a changing political climate: What was once called an “alternative” political space in urban centres is now occupied by the Rastriya Swatantra Party, under the leadership of a populist strongman. Rabi Lamichhane’s neonatal party claimed a worthy 20 seats in its first electoral bid and then sullied the image of alternative politics as yet another rat race to power, albeit through an alternative track. Essentially, the idea of alternative politics has been confined to those who are valiant fighters for justice and accountability only until they get a taste of political power.

While Bibeksheel Sajha has an uphill task of establishing its relevance as a credible alternative force, it has already had a promising start by electing women in leadership positions. In our testosterone-fueled political sphere, it is indeed a refreshing change, worthy of emulation by every party in the political race today. As of now, mainstream parties have considered women leaders no more than fillers, to be given their legally-mandated share—and no more. Ingrained misogyny among top political leaders has created structural barriers for women who want to come to the forefront of participatory politics. Nothing else explains the poor representation of women coming through direct elections in the Parliament and in leadership positions of political parties.

The November 2022 elections provided ample illustration of this misogyny in political parties: The CPN-UML, which fielded 141 candidates for the House of Representatives, gave only 11 tickets to women under the first-past-the-post electoral system. The Nepali Congress, which had 91 candidates, had just five direct election candidates. Likewise, the CPN (Maoist Centre), among its 47 candidates, gave tickets to just nine women. As a result, these parties had to set aside most of their proportional representation seats to women to fulfil the mandatory 33 percent constitutional requirement.

Waxing eloquent about women’s empowerment in speech and actually leaving space for women to come and take leadership positions are, the major parties have shown, two different things. As sorry is the state of political parties when it comes to welcoming women’s leadership. Women leaders routinely complain of being sidelined in intra-party affairs. But it would be a mistake if the top male leaders believe they can continue to confine women’s leadership to tokenism. (Also, with women making up over half the country’s population, it would also be a politically unwise electoral strategy.) Women taking top leadership positions—in all fields, but more so politics—should not be an exception but the norm. Nepali society is more welcoming of women’s leadership than the old patriarchs of established parties would have us believe. Baskota and Darshana are just two of many women active in today’s politics who are capable of driving their respective parties.

8.22°C Kathmandu

8.22°C Kathmandu