Editorial

What about ‘Gaushala 26’?

The survivor has been rendered invisible ever since she filed the case against Sandeep Lamichhane.

The haste with which the Cricket Association of Nepal (CAN) has lifted the ban on Sandeep Lamichhane, the rape-accused former national men’s cricket team captain, just days after he was released from custody on bail, once again exposes entrenched misogyny in Nepal’s public institutions. Ever since the accusations against Lamichhane came to light, the association has tried to give him the benefit of doubt, if not to establish his innocence. The cricket governing body, led by a man (of course!), seems to be in a hurry to sanitise the image of one of its disgraced members, possibly in the fear that his legal prosecution and banishment from the game could start a domino effect; it is hard to believe that those looking to protect Lamichhane, despite the overwhelming evidence of wrongdoing against him, don’t have something to hide themselves.

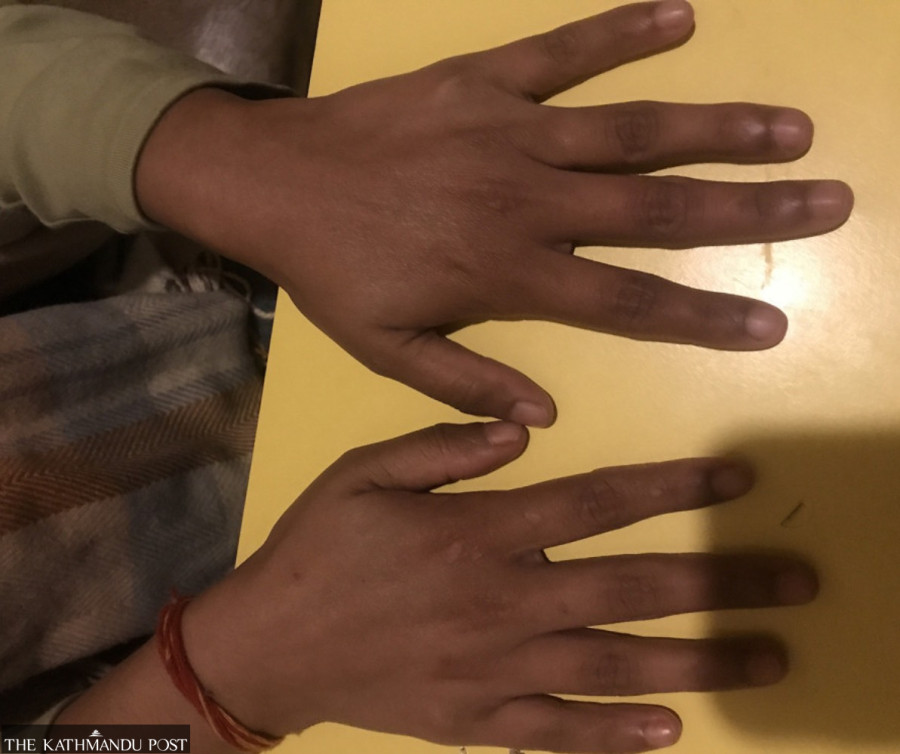

Contrast this with how the survivor has been rendered invisible and inconsequential in the past six months since she filed the case against Lamichhane, and we have a clear picture of where Nepali society today stands on a woman’s autonomy and agency. Speaking with Kantipur daily’s Tufan Neupane, the survivor narrated her anguish at seeing the accused get a grand welcome when stepping out of custody even as she has been pushed into oblivion. It is as if the society itself has become a jail for the survivor, as she risks social ostracisation and physical violence if she sheds the garb of anonymity even as the accused could potentially get to prove his mettle on the pitch again, as if nothing happened. The 22-year-old leg-spinner has continued to garner widespread sympathy from his loyal fans—mostly men, one assumes—who refuse to believe their hero is capable of doing anything wrong. The survivor, meanwhile, has to live with the ignominy of being rendered a label, ‘Gaushala 26’, a fictional identity that the criminal justice system has given her.

This case is just about the perfect illustration of how Nepal’s institutions—and the society at large—continue to operate with patriarchal mindsets that are quick to blame women when that patriarchy is threatened in any way. The association should at the least have waited till the final court verdict before it decided to revoke the ban, so as not to further victimise the victim. The cricket governing body has disgraced itself by failing to stand by the survivor, or at least to maintain a studied neutrality until the legal case against Lamichhane was settled, one way or the other. But, again, the scope of this incident is not limited to one Nepali institution coming to the rescue of one of its disgraced members.

The patriarchal state wants to project a progressive image through tokenism: Agreeing to appoint a few women to this agency or that ministry even while covertly working to deny greater space and voice to women in all aspects of life. In this social setup crafted for the benefit of men, sexual violence against women continues to be rampant, forcing the victims into untold psychological suffering and social ostracisation. The harrowing details of what Lamichhane did to the survivor, which she recounts in the Kantipur report, has shaken the collective conscience of Nepali society. Apparently, they mean nothing to Lamichhane’s ardent fans, whether they are in the cricket governing body or out on the street celebrating his release.

21.18°C Kathmandu

21.18°C Kathmandu