Editorial

Reluctant federalists

Troublingly, partners in the current ruling coalition have little to say about strengthening federalism.

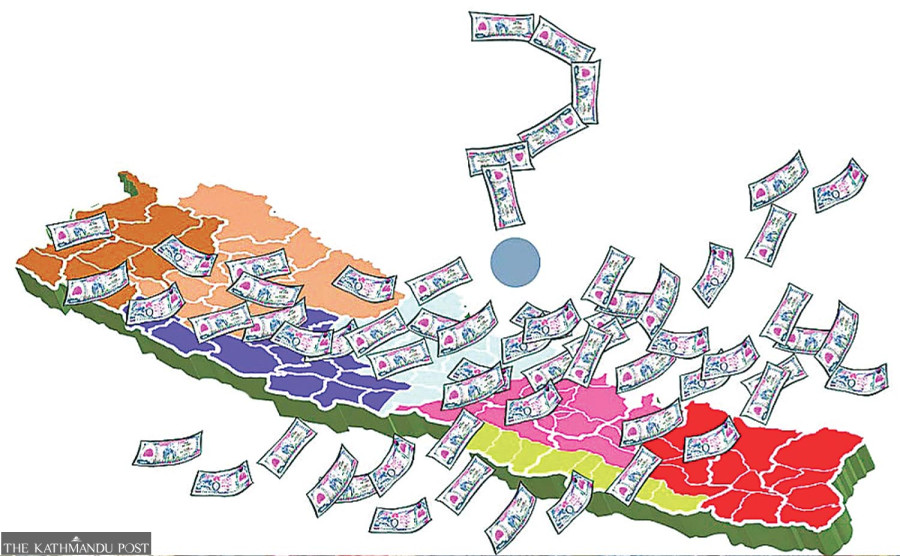

At a critical juncture in recent Nepali history, when the country was going through a rough transition after the abolition of constitutional monarchy, Pushpa Kamal Dahal became a passionate champion of republicanism, secularism and federalism. When the Constitution of Nepal, 2015 made those ideals the fundamental features of Nepali society, it was no small feat of Dahal and others like him those who championed those ideals. After seven years, republicanism and secularism have found a firm footing. However, federalism continues to falter for lack of laws required to fully implement it, amid widespread suspicion and criticism that it is too costly for a small, poor country like Nepal. The legal instruments to make federalism functional are still not in place seven years after the promulgation of the constitution and inception of federalism. As the newest executive head of the state, Dahal is now in charge of implementing federalism in its full spirit. Dahal will not have it easy—that is, if he is first committed to making federalism in Nepal work.

The powers that be are still reluctant to devolve power to the provinces and the local levels. Leading the brigade of reluctant federalists is the CPN-UML, whose chairperson KP Sharma Oli is a known sceptic of federalism, having infamously claimed that aiming for federalism was akin to travelling to the United States on a bullock cart. Oli is now joined by Rabi Lamichhane, who has reservations with the country’s provincial setup. His party, the Rastriya Swatantra Party, did not even field candidates for the provincial assembly elections claiming federalism as it is practised is not feasible. And Oli and Lamichhane are joined in the ruling coalition by Rajendra Lingden, who represents the archaic Rastriya Prajatantra Party, a party still fascinated by the prospect of bringing back monarchy from the dead, scrapping federalism, and undoing secularism in favour of a unitary Hindu state. In such a scenario, there is little to expect from the current coalition government in terms of fully implementing federalism.

What is even more alarming is that the partners in the coalition claim to be supporting Dahal based on common agendas. Although they are yet to elaborate on those agendas, they have hinted that their most important agenda is corruption control. They have little to say as yet on secularism, federalism and republicanism. Not that political ideology has had any effect on making and unmaking of coalitions in contemporary Nepali politics, but there is little doubt that the political ideologies of the current coalition partners often clash. There is hardly any trust among its members, as it is a rebound of jilted parties from other coalitions. Even calling it a marriage of convenience would be unjust. It is, rather, a coalition of opportunism—just to grab power in Singha Durbar.

As the coalition is a patchwork of parties with ideologies belonging to left, right and centre, the likelihood of them coming together on federalism is low. In such a scenario, federalism is likely to be left in the lurch, like in the past. The question is whether Dahal has the willpower to further strengthen the federal project even by going against his coalition partners. Seeing the way he has lusted for power in the past few years, there is little to hope. But if the rumours of him wanting to leave behind a lasting legacy this time are even partly true, one of the best ways he can do so is by strengthening the federal project by delegating more rights and resources to the provinces. And to do so, he must push to amend the requisite laws, even if that entails leaning on his coalition partners.

18.12°C Kathmandu

18.12°C Kathmandu