Editorial

An urban tragedy

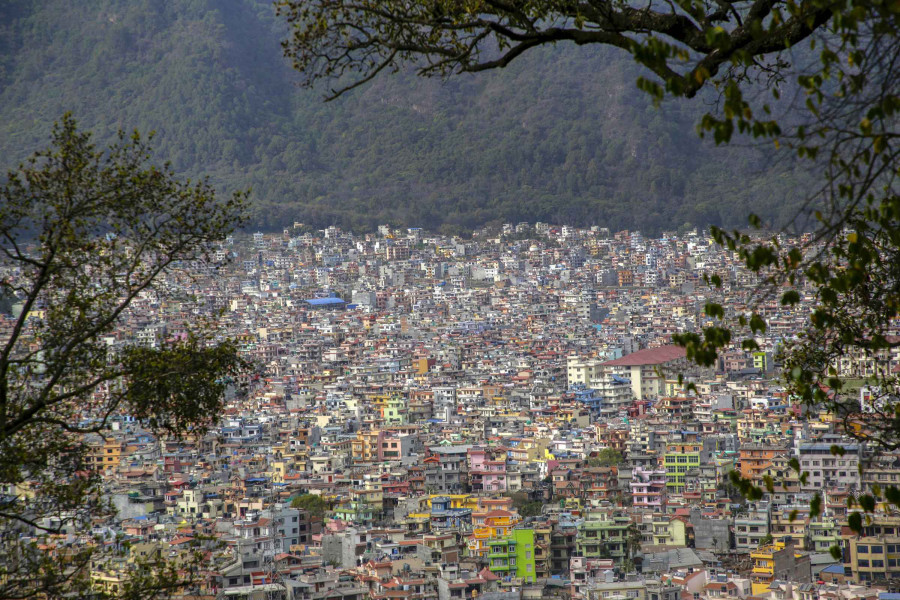

Every bit of free space is being used up to erect concrete structures to accommodate the ever-growing population.

The Central Bureau of Statistics has published various facts and figures in its census report. The figures indicate a particular cause for concern. One, there is a lopsided concentration of people in the Tarai region. Two, just over 66 percent of the population resides in urban areas. With 68 percent of the world’s population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, the figure reflected may tempt people to believe it is in line with global trends. But urbanisation is pretty shambolic in Nepal, and there are numerous problems that the administration needs to be mindful of.

Towns and cities have seen unprecedented expansion in the last two decades, but it has been largely unplanned and pretty haphazard. There is no thought to preserve any natural aesthetics when building houses, and more often than not, the access ways to residential properties are ill planned. And with more and more people moving into urban areas, it has led to an acute shortage of accommodation, and consequentially sky-high rent rates have forced newcomers to live in squalid conditions. There’s nothing rosy for the early settlers either. People living in cities lack basic amenities.

Access to clean, affordable drinking water is still a significant problem in the cities, especially for residents in Kathmandu. People’s expectations were dashed when the much-awaited Melamchi Water Supply Project had to stop supplying water to the valley to carry out repair works after barely being operational for a few months. Waste management is another issue where no lasting solution has been reached; often, during the monsoon season, residents of Kathmandu have to endure piles of rubbish strewn all over the city. And to make matters worse, there is the issue of raw sewage being brazenly dumped in rivers making it unbearable to even walk along the banks, let alone reside there.

The inadequacies of solid waste management, if not resolved, could lead to environmental degradation and aggravate public health problems. These are just a few examples of the disorganised state of operations. The history of urban planning is a new concept to the Nepali psyche. The concept of urban planning was only introduced in the third national five-year plan 1967-71, and it is pretty evident that nothing much has been done to cater to the needs of the masses of people flocking to urban areas.

Every bit of free space is being used up to erect concrete structures to accommodate the ever-increasing flow of people, often encroaching on areas deemed uninhabitable by the old locals. The disastrous effects were visible for all during the earthquake in 2015 when buildings built on loose grounds gave way and led to their collapse, causing widespread damage and destruction and loss of life. But the way urbanisation has continued, it seems the hazards of high-rises have been all but forgotten. There is an urgent need to redress the ongoing problem of continued urbanisation, and if we are to carry on at this pace, stretching every bit of resource at our disposal, we could be looking at a ticking time bomb.

20.12°C Kathmandu

20.12°C Kathmandu