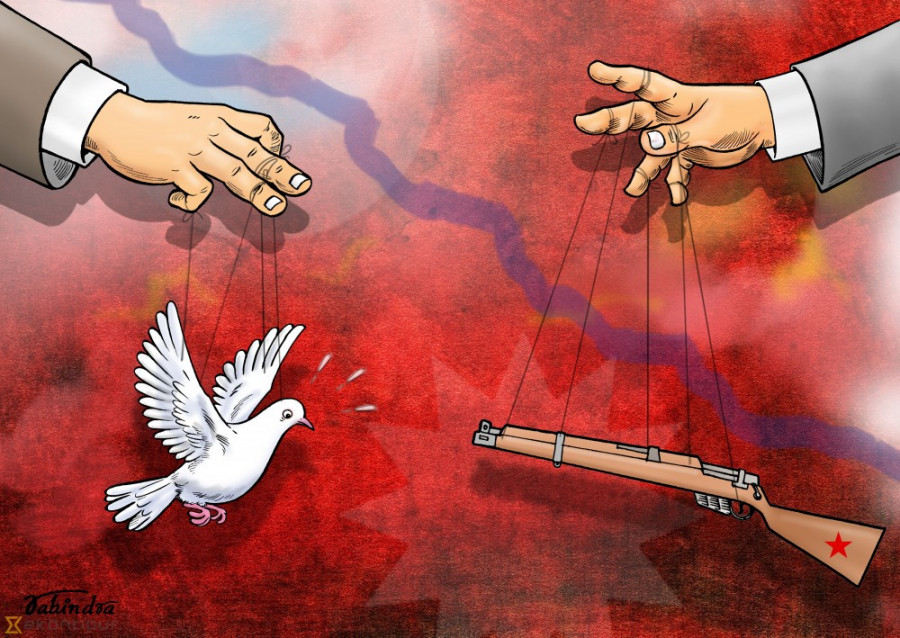

Editorial

Fractured peace

The so-called representatives of the working class are the new elites of Nepal.

November 21, 2006, ended one of the most tumultuous periods for modern Nepal as the CPN (Maoist) and the Government of Nepal agreed on a truce. It marked the formal end of the insurgency in Nepal. It provided a window of opportunity for the warring factions to find some middle ground to attain lasting peace and uplift the nation from the pangs of poverty toward economic prosperity through an egalitarian model. How far have we come though? Have the objectives of the peace accord been accomplished? We can copiously agree to achieve peace only if the definition of peace is limited to a period free from a constant state of war.

But peace and stability in the present scenario seem to be a far cry. The principles of justice continue to be disregarded as the stakeholders of the conflict see opportunity in collective amnesia. No reparations to the victims have begun, nor can we see any hope of economic prosperity with political parties constantly jostling for privileges and fulfilling vested interests. The general population faced the wrath of the insurgency, whether it was atrocities carried out by the state or the Maoist insurgents. And despite The Comprehensive Peace Accord categorically expressing the commitment to impartial investigation on crimes against humanity, the issue has been continually confined to hollow rhetoric. It seems to be a constant case of assurances without actually having any intention to see through to completion.

In an article published in The Kathmandu Post to mark the 15th anniversary of the peace deal, Pushpa Kamal Dahal, the chairperson of the CPN (Maoist Centre), claims that the signing of the peace accord was a success worthy of emulation and that it had managed to achieve peace and democracy. While he credits himself and his party for uplifting the marginalised, in actuality, after all these years, the marginalised and the victims have yet to avail any tangible benefits and privileges he mentions. Privileges and positions of power are still within the purview of the elites. The narrative remains the same. What has, in fact, changed are the actors.

Those who purport themselves to represent the common person are the elites of Nepal today. The fruits of democracy are yet to permeate through to those at the bottom of the economic and social strata. Until that happens, the new elites of today have no moral basis for such empty declarations. When a functioning parliament is prorogued, and the authorities resort to ordinances in facilitating party split rather than meeting the nation’s pressing concerns, such actions do not in any scenario conform as being representative of democratic behaviour.

While peace is the cornerstone of stability and progress, prosperity can only be guaranteed through political leadership. Societal progress requires sacrifices; the people have endured much hardship to entrust the representatives to fulfil their hopes and aspirations. After years of conflict and democratic transition, what we now have is a polity that evokes pessimism among the people. This is not the kind of peace and democracy the people laid their lives for. It is now up to the politicians to realise their share of the bargain. Until then, we can at least hope for some maturity on their part.

13.12°C Kathmandu

13.12°C Kathmandu