Columns

Nepali peace process as a global model

One reason why it has become successful is that it adopted a home-grown approach to end conflict.

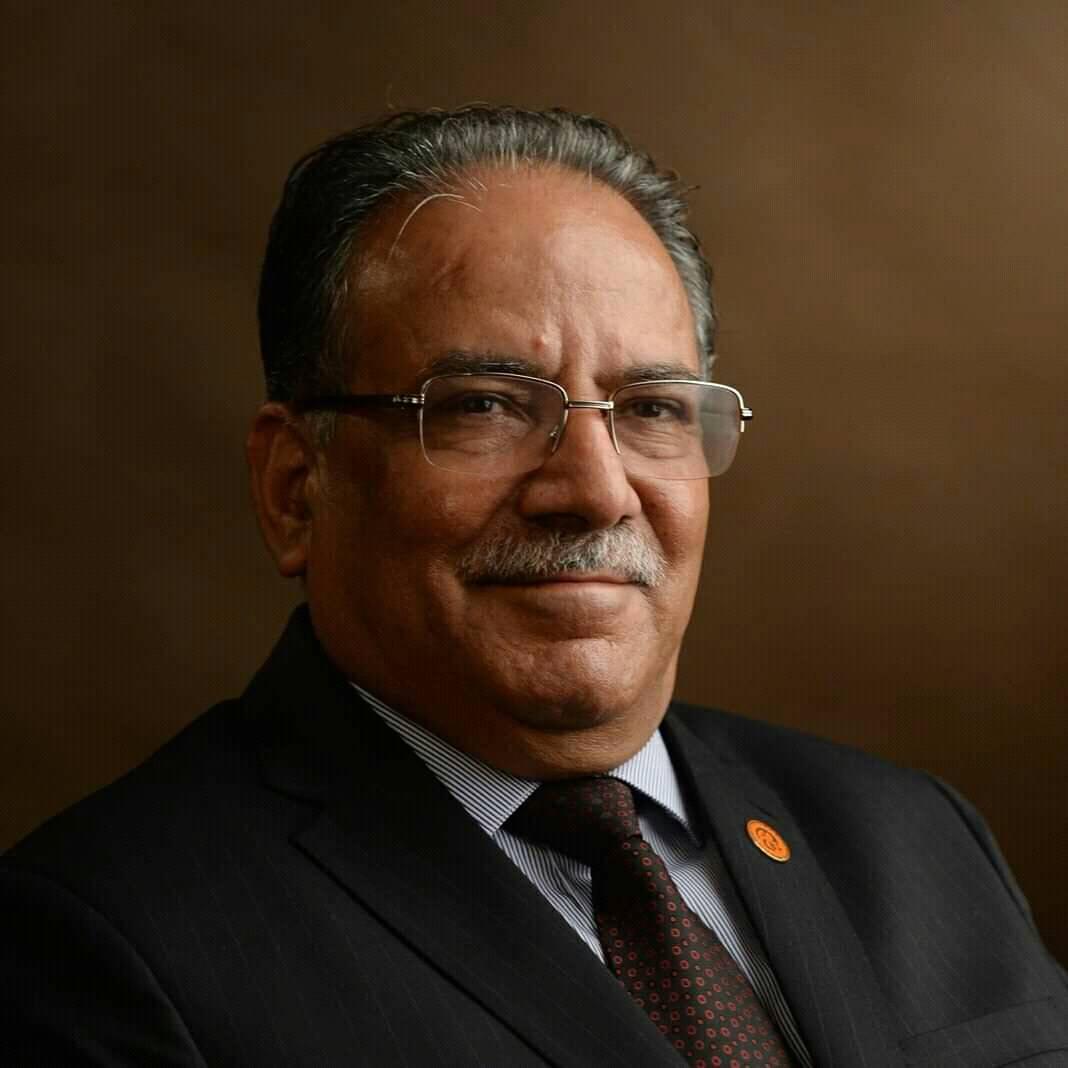

Pushpa Kamal Dahal 'Prachanda'

As we celebrate the 15th anniversary of the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement between the Government of Nepal and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) today, it is also time to celebrate our party's consistent commitment to peace and democracy.

The Nepali peace process was started by the CPN-Maoist party under my leadership in early 2005. When King Gyanendra usurped power in February 2005, overthrowing a democratically elected government, we decided to seize the opportunity for peace triggered by the authoritarian takeover. We immediately intensified dialogue with a coalition of other mainstream political parties, known as the Seven Party Alliance (SPA).

We convinced the SPA about the need to elect a Constituent Assembly (CA) to draft a new and fully democratic constitution. This agreement became the cornerstone of Nepal's peace process, which, in turn, has become one of the most successful peace processes in the post-Cold War global context.

We have also been committed to peace from the beginning of our political struggle. Our vision has always been peace for all segments of the Nepali people. Before our revolution started in 1996, peace was limited to the elites and primarily to urban areas. A majority of the people in rural areas, particularly the marginalised sections of Dalits, Muslims, Madhesis, Janajatis, women, peasants and labourers, suffered an inescapable cycle of systemic and structural violence. They did not have the same sense of peace that the privileged few enjoyed. We wanted to change this condition and work towards attaining peace that included the Nepali society's margins.

While we have focused on inclusive peace, we have also prioritised the democratic means to achieving our goals. That is why we demanded an election to the CA to represent diverse communities in Nepal, especially the historically excluded groups, to draft the new framework for Nepal. Earlier peace initiatives in 2001 and 2003 had failed because the mainstream political parties refused to meet our minimum democratic demand for the CA elections. The SPA decided to collaborate with the Maoist party only after King Gyanendra pushed them to the corner with the army's support in February 2005. In this sense, the Maoist party can be seen as the main initiator of Nepal's peace process.

Our consistent commitment to multi-party democratic competition is evident in our participation in five democratic elections, including at the local and provincial levels, since the peace process began. Whereas rebel groups in several other countries such as Angola, Ethiopia and Kenya have resorted to violence or coercive power-grabbing after losing elections, we have gracefully accepted all the results even when results were not in our favour.

As we celebrate the 15th anniversary of the peace process, I want to remind the Nepali people and the international community about our remarkable achievements. As part of the peace process, the country has experienced tremendous socio-political reforms. Nepal has graciously transitioned into a modern and democratic federal republic, ready to face the 21st-century world, which is different from the autocratic, centralised and feudal kingdom that Nepal was before the advent of the peace process.

Today, Nepal is one of the most progressive countries globally regarding constitutional provisions regarding gender and social inclusion. We have guaranteed 40 percent representation of women at the local level and 33 percent representation in other decision-making positions, including in Parliament. We have promoted the inclusion of excluded groups such as Dalits in the decision-making positions at various levels through constitutional provisions. Considering the less than 6 percent representation of women and less than 1 percent representation of Dalits in the three directly elected parliaments in the 1990s, this is sterling progress.

Significantly, there has been no relapse of large-scale violence throughout Nepal's peace process, unlike what many other post-conflict countries experienced. Clearly, Nepal's peace process has laid a foundation for a sustainable peace for all Nepalis.

While sharing the positive gains resulting from the peace process, I must acknowledge some shortcomings. The issue of transitional justice is yet to be settled in a way that satisfies the mainstream international community, and we have not been able to fulfil the aspirations of the Nepalis for greater economic development. Nevertheless, when compared to those of others around the world in the post-Cold War era, Nepal's performance in the peace process has been extraordinary.

In the conflict-ridden African region, peace processes have had mixed results. In the Central African Republic, which is a landlocked and least developed country like Nepal, decades-long attempts at the peace process, with multiple peace agreements, have failed to end armed violence. Violence lingers on in Sudan, whose Comprehensive Peace Agreement (2005) is a year-and-a-half older than ours. Closer home in Asia, marked by major armed conflicts, peace processes appear fragile. In Sri Lanka, the path to seeking peace has been through military means rather than political negotiations, which, as per the United Nations, have resulted in numerous civilian deaths.

Peace processes in many parts of Latin America have been equally questionable as many countries continue to suffer from sustained violence even though armed conflicts have ended formally. Recently, in Colombia, the peace deal signed in 2016 after four long years of negotiation was rejected by the Colombians. As per media reports, violence and insecurity ravage many parts of the country today.

Apart from these examples, two major peace-building initiatives in the 21st century—Afghanistan and Iraq—have, despite massive global investments, failed to end violence and lay the foundations for stable democracies. In comparison, Nepal's peace process has been successful, notwithstanding the relatively limited attention and support by the club of rich and powerful states.

One reason why Nepal's peace process has been successful is that it has adopted a home-grown model. The failure of most peace processes in the conflict-affected areas of the global south following the end of the Cold War had cautioned us about the limitations of the dominant models of peace, commonly characterised by the direct involvement of Western states and their liberal institutions, including the United Nations. These templates have suffered from inherent flaws such as Western ethnocentrism, ignorance of local political dynamics, and a lack of accountability towards the targeted group. Failures of peace initiatives have impacted the lives of millions of people in terms of everyday peace in conflict-ridden countries.

To avoid these risks, we envisaged our own model of peace in Nepal. This model is premised on the notion of peace for all Nepalis by promoting social justice and full democracy. Nepal's blueprint for peace has also been rooted in the ordinary people's desire for peace shaped by our rich cultural and spiritual heritage of peace.

There seems to have been some confusion about Nepal's locally driven approach to peace. A few external states and institutions have claimed that they were the supervisors of Nepal's peace process. As the key architect of Nepal's peace process, I can confidently claim that this is not true. It was primarily a locally driven initiative. This does not mean that we did not engage with international friends and partners. Initially, it was essential to take India and China into confidence due to geopolitical sensitivities. We also took other like-minded international partners on board.

Yet, there was no formal international or third-party mediation when the 12-Point Understanding between the Seven Political Parties and the Nepal Communist Party (Maoist) was signed in November 2005. While there has been a direct third-party or international meditation in most contemporary peace processes, that was not the case in Nepal.

As the peace process progressed, we sought support from various international partners based on our needs. We formally invited the United Nations for support on five specific areas, the most important of which was monitoring arms and armed personnel on both sides. Again, compared to other ongoing peace processes in the post-Cold War era, where the United Nations has played a more assertive role, including maintaining peace-keeping operations, the organisation's mandate in Nepal was limited in scope and time.

After the United Nations Mission to Nepal ended in 2011, we completed the remaining crucial parts of the peace process, such as integrating arms and armies on our own, with Nepali political leaders making the key decisions.

When I initiated the peace process in 2005, the SPA leader, Girija Prasad Koirala of the Nepali Congress party, was my co-partner. We worked out most issues of the peace process together. During our last meeting at the hospital, he said that the full responsibility of the peace process was solely on my shoulders after him. It was not an easy responsibility, considering the constant attacks on the peace process from a few national and international forces.

For me, it was like walking a tightrope. I was forced to make endless compromises to sustain the peace process. At the same time, I could not give up on our core ideology of social justice. Were my compromises worthwhile? This will be for the coming generation of the new federal democratic republic of Nepal to judge.

For now, it is time to celebrate the successful 15 years of our peace process. We need to remember that Nepal's peace process is not entirely out of danger yet. I am doing my best to sustain its success. And I want to take this opportunity to remind the international community that, in a global context marked by frequent failures of peace processes, the Nepali model of peace could offer inspiration for people of other countries reeling under direct violence.

19.12°C Kathmandu

19.12°C Kathmandu