Columns

Chasing a hero who isn’t

Democracy thrives through the collective act of institution building rather than the heroics of populist activists.

Dinesh Kafle

Free speech believers and social media warriors alike had a considerable meltdown for much of the past two weeks when Ashika Tamang, the self-identified social activist known for bringing overcharging shopkeepers to their toes, was arrested twice. She was first arrested by the Kathmandu District Police for allegedly misbehaving with police officers on January 15, and then by the Bhaktapur Police for allegedly disrupting fee collection at a footbridge in Sanga, Bhaktapur. The arrests led to a deluge of sweeping statements on the extent of free speech and right to protest—in activistspeak, democracy had gone down the drain; for her detractors, disruptive behaviour in the garb of activism calls has no remedy than incarceration.

There must have been some nuanced, moderate voices too, but they were perhaps lost in the cacophony of the extremes. And so, at the risk of sounding like a fence-sitter throughout the drama, I submit that Tamang’s arrest was just as arbitrary as her brand of activism. Populist activists with seemingly unreasonable social behaviour emerge from the fault lines of democracy. The fault lies entirely in the functioning of the democracy; but make no mistake, activists of the Ashika Tamang brand are not the heroes we need despite the hopes of justice and fairness they offer those sick with the system. Democracy certainly indulges the individuals who claim to lift us out of our drudgery, but when their theatrics stray to the melodramatic, all we get is a poor line-up of social anti-heroes.

Heroes we don’t need

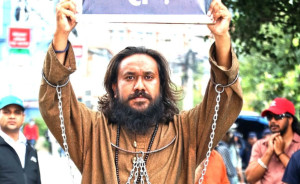

In the past couple of years alone, in our theatres of democratic politics, we have seen several such individuals with a great flair for performativity slowly metamorphose into the heroes we don’t really need. A firebrand television showman with anti-corruption slogans who further muddied the water he set out to clean; an accomplished rapper who turns deaf ears to the cries of the poor trying to join hand to mouth; a charismatic organiser whose idea of democratic participation revolves around rallying people carrying stones on their backs while remaining stone-hearted for the people who question him. We continue to become enraptured by their public performances even as we look for a new cast of characters for fresh twists and turns.

No, our heroes aren’t good for nothing. Notwithstanding our likes or dislikes for their melodrama, they are populist manifestations of our secretly dissident selves. As the citizens of a country where no public institution seems to work the way it should, we are waging a million individual mutinies at once. But we are too bridled by our personal insecurities, family responsibilities and social etiquettes to go out and fight our fights against the system and the society on a daily basis. Worse, we do not have the agency to launch such fights, as those who claimed to fight on our behalf have already become coopted by the system. At such critical junctures, our populist hero emerges out of the woods armed with angry-looking eyes and gun-like cameras and flanked by cheerleaders known these days as YouTubey.

As we gaze into our smartphones witnessing the disruptive antics of our populist hero, we shift in our chairs hoping we weren’t so diffident, that we could as well have performed a few of our mutinies in the public, that we missed a golden chance to become a hero ourselves. But at the same time, we are thankful to the hero for becoming the hero we couldn’t become, and as a gesture of gratefulness, we like, share and subscribe and remain satisfied that we have done our duty. As loyal consumers of populist melodrama, we are contributing to building the society of the spectacle. But building a democratic society is a different ballgame altogether—what we need is a retrofitting of the institutions that have been weakened due to a collective mix of their inherent corruptibility, political subterfuge and public indifference.

Institutionalising democracy

No matter the ulterior motives of the populist heroes of various hues, they make sure to pick the key words of democracy such as justice and fairness, and that is what makes their case appealing. After all, there is no apparent harm in someone lambasting airline companies that delay flights and fail to inform their passengers, shouting at restaurant managers who overcharge their customers, or shoving a man pissing on the roadside. After all, until recently, the citizens of this country got their adrenaline rush from a collective fantasy of huddling corrupt political leaders in Tundikhel and breaking their noses with a round kick—it’s a different matter altogether that the man who wanted to launch the round kick became eligible to receive one. Or even rallying a legion of real victims of corporate fraud to canvass your motive to defraud banks on billions of rupees worth of loan.

A fundamental term of democratic engagement is that it allows even for unreasonable voices to be heard, in the hope that reasoning trumps them. But at the same time, reasonable behaviour is a bare minimum requirement for meaningful engagement, although a lack of the same should not translate into legal action as exemplified by the back-to-back incarceration of Ashika Tamang on flimsy grounds. Ultimately, therefore, the focus should be on the institutionalisation of democracy rather than the heroisation or demonisation of individuals. A democratic country like Nepal has all the institutions required to ensure justice and fairness in public matters through its regulatory and oversight mechanisms. The administration that punishes a citizen for asking questions and causing disruption while it cannot even address the questions received through “Hello, Sarkar!” has much introspection to do and many questions to answer.

No prize for guessing what the government and its functionaries must do rather than jump into reactionary and retaliatory action against citizens: Use your resources in strengthening institutions rather than harass populists and the public alike. Where State or government institutions fail to fulfil their duties, intermediary institutions such as political parties and media should continue to represent people’s concerns. But most Nepali political parties of even a tangential public repute are either already in the government or are trying to slither into the government; mainstream media is either struggling to regain its legitimacy, or worse, already coopted by political parties or corporates. No wonder populists continue to hog the limelight much to the chagrin of powers-that-be.

16.12°C Kathmandu

16.12°C Kathmandu